Water boils. It's the most basic fact of the kitchen. You turn the dial, the bubbles start dancing, and suddenly you’re at that magic threshold of 100 degrees C to Fahrenheit conversion.

It’s 212.

That’s the number everyone remembers from middle school science, but honestly, it’s rarely that simple once you actually start cooking or working in a lab. If you’re standing at the top of a mountain in Colorado, your water isn't hitting 212°F. It’s hitting maybe 202°F. You’re waiting longer for your pasta to cook, and your coffee tastes different. Temperature is a fickle thing.

The relationship between Celsius and Fahrenheit isn't just about math; it’s about how we’ve decided to measure the world around us. Anders Celsius and Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit had very different ideas about what "zero" should look like. Celsius went for the freezing point of water. Fahrenheit? He was messing around with brine solutions and human body temperature, which is why his scale feels a bit more "human-centric" for weather but totally chaotic for science.

The Math Behind 100 Degrees C to Fahrenheit

Let's get the technical stuff out of the way. If you want to convert any Celsius temperature to Fahrenheit, you aren't just adding a few digits. You have to scale it.

💡 You might also like: Why an Image That Represents a Confident Stick Figure Drawing Still Works Better Than AI Art

The formula looks like this:

$$F = (C \times \frac{9}{5}) + 32$$

Basically, you take your 100, multiply it by 1.8 (which is just 9 divided by 5), and you get 180. Then you tack on that 32-degree offset because Fahrenheit’s "zero" is much lower than Celsius’s.

$180 + 32 = 212$.

Done. Easy. But why do we use two different systems? It’s mostly historical stubbornness. Most of the world realized that base-10 systems (Celsius) make way more sense for calculations. The United States, Liberia, and Myanmar just stuck with the old ways. It’s like using a yardstick when everyone else is using a meter. It works, but you’re doing extra mental gymnastics every time you read a recipe from a European blog.

Why 212°F Isn't Always the Boiling Point

Here is where it gets weird. We say 100 degrees C to Fahrenheit is 212 degrees, but that only holds true at sea level. This is called "standard atmospheric pressure."

Air has weight. When you’re at the beach, there’s a massive column of air pressing down on your pot of water. That pressure keeps the water molecules from escaping into steam. You need more energy—more heat—to break them loose.

Move to Denver, the "Mile High City," and there's less air above you. The pressure is lower. The water molecules can escape into the air much more easily. At 5,280 feet, water boils at about 203°F (95°C).

If you try to soft-boil an egg at high altitude using a "3-minute" rule, you’re going to end up with a runny mess. You have to cook it longer because the "boiling" water isn't actually as hot as it would be in Miami. This is a massive pain for bakers. High-altitude baking requires adjusting leavening agents and liquid ratios because 212°F simply doesn't exist in their kitchens.

Beyond the Kitchen: Industrial and Scientific Reality

In a laboratory, hitting 100°C is a benchmark for sterilization. Autoclaves—those big pressurized steamers used to kill bacteria on medical tools—don't just stop at 100°C. They use pressure to push the temperature past the normal boiling point.

Think about a pressure cooker. By sealing the lid, you’re artificially creating a high-pressure environment. This forces the water to stay liquid even as it climbs to 120°C (248°F). This is why a tough piece of beef that usually takes four hours to braise can turn into butter in 45 minutes. You’re hitting it with heat that is physically impossible in an open pot.

The Human Element of the Scale

We often talk about these numbers in terms of weather, even though 100°C is lethal for a human. But understanding the jump from 100 degrees C to Fahrenheit helps us appreciate the precision of our own bodies.

Your internal temperature is around 37°C (98.6°F). If that number climbs just 3 or 4 degrees Celsius, you’re in the danger zone for heatstroke. If it hits 42°C (107.6°F), your proteins literally start to denature. That’s less than halfway to the boiling point, yet it’s the difference between life and death.

Real-World Conversion Hacks

You don't always have a calculator. If you’re traveling and see a temperature in Celsius, here’s the "good enough" method most expats use:

- Double the Celsius number.

- Subtract 10%.

- Add 32.

So, for 100°C:

Double it = 200.

Minus 10% (20) = 180.

Add 32 = 212.

It works perfectly for 100, and it stays pretty accurate for weather-related temps too. If it’s 20°C outside:

Double it = 40.

Minus 10% (4) = 36.

Add 32 = 68°F.

(The actual answer is 68°F. The "cheat" is perfect here).

The History of the 212

Why 212? It seems like such an arbitrary number.

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit originally wanted his scale to be based on three points:

- The freezing point of a water/salt mix (0°).

- The freezing point of plain water (32°).

- The temperature of the human body (initially set at 96°).

Wait, 96? Yeah, his initial measurements were a bit off, or maybe he just had a cold that day. Later, the scale was redefined so that the interval between freezing and boiling was exactly 180 degrees. Since freezing was already 32, adding 180 got us to 212.

It’s a bit of a mathematical "fix" to make the boiling point land on a whole number. Celsius, or "Centigrade" as it was called until 1948, is just cleaner. Zero is frozen. One hundred is boiling. It fits the metric world beautifully.

Common Misconceptions

People often think that 100°C is the "hottest" water can get. Not even close.

Superheated water is a real thing. If you put very pure water in a very clean glass bowl and microwave it, you can actually heat it past 100°C without it boiling. It’s "superheated." The second you drop a spoon or a tea bag into it, you provide "nucleation points," and the water can literally explode out of the cup as it flash-boils. It's incredibly dangerous and a common cause of kitchen burns.

On the flip side, steam can be much hotter than 100°C. We call this "dry steam." While "wet steam" (the stuff you see coming off a kettle) is right at the boiling point, industrial boilers can heat steam to 400°C or higher to turn turbines for electricity. At that point, the steam is invisible. If you walked past a leak of 400°C steam, it would cut through skin like a laser before you even saw it.

Applying This Knowledge Today

Understanding the jump from 100 degrees C to Fahrenheit is basically a rite of passage for anyone working in global industries. Whether you're a software engineer localizing a weather app or a chef following a French sous-vide recipe, these numbers matter.

Actionable Insights for Temperature Accuracy:

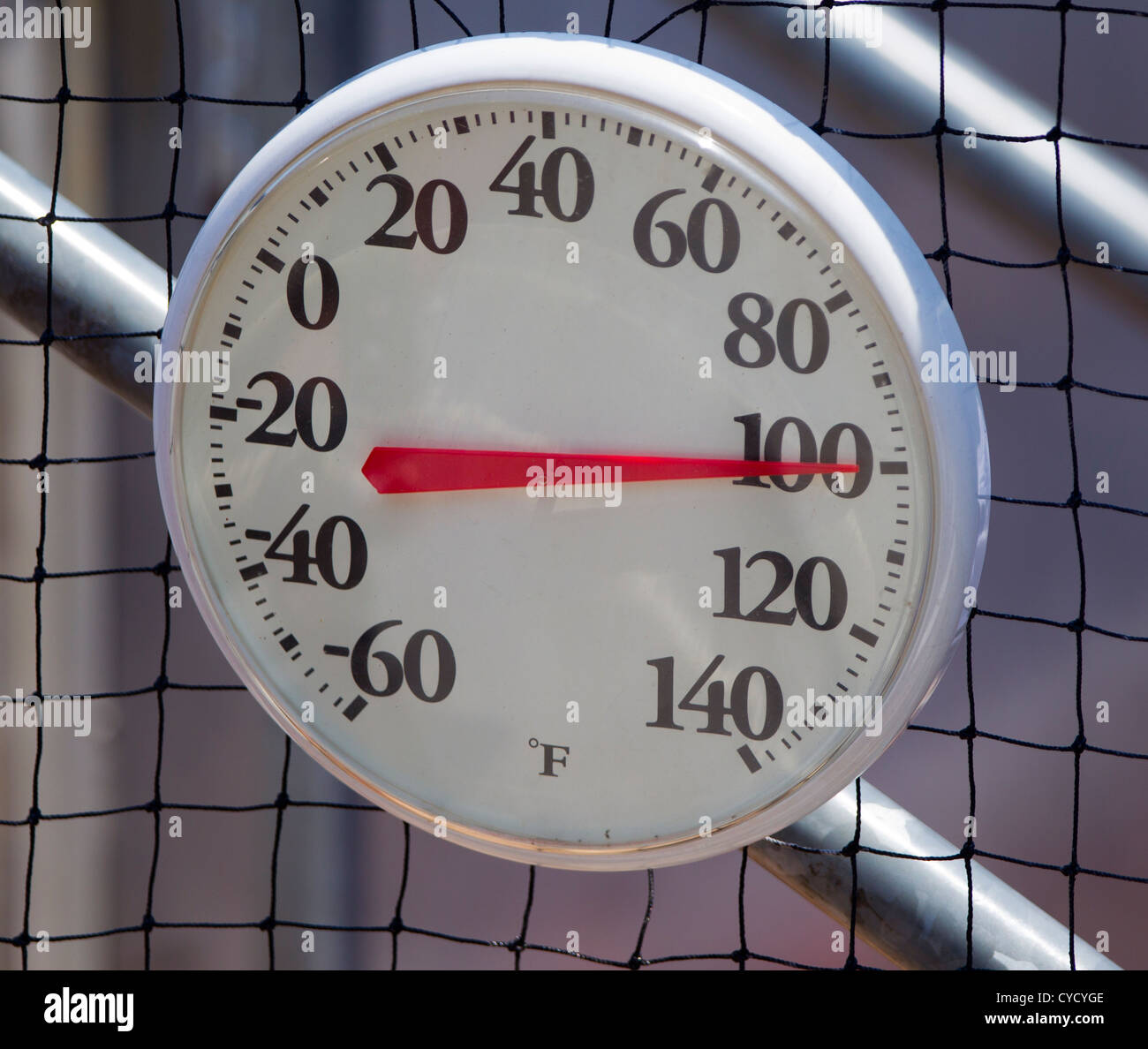

- Check your altitude: If you live above 2,000 feet, buy a thermometer and test your boiling water. Don't assume it's 212°F. Knowing your local boiling point is the secret to consistent cooking.

- Calibrate your equipment: Most kitchen thermometers are off by a degree or two. Stick your probe into a pot of rolling boiling water. If it doesn't read 212°F (at sea level), you know your offset.

- Think in Celsius for Science: Even if you love Fahrenheit for the weather, try using Celsius for your coffee brewing or bread making. The 0-100 scale makes it much easier to track percentages of heat transfer.

- Safety first: Remember that steam burns are often worse than water burns because steam carries the "latent heat of vaporization." It releases a massive amount of energy the moment it hits your cooler skin and turns back into liquid.

Converting 100 degrees C to Fahrenheit might seem like a simple Google search, but it's really the gateway to understanding physics, history, and the way we interact with the physical world. Next time you see a pot of water start to bubble, you'll know there's a lot more going on than just a number on a dial.