Forget the "Downton Abbey" rose-tinted filters for a second. If you walked down a street in London or New York in 1912, you wouldn't just see a sea of giant hats and lace. You’d see a society in the middle of a massive, uncomfortable wardrobe transition. It was a weird year. Truly. 1912 fashion for women was caught in this awkward, beautiful tug-of-war between Victorian modesty and the terrifyingly modern "New Woman."

People usually think of 1912 and just picture the Titanic. While the disaster obviously looms large, the clothes people wore on those decks represented the absolute peak of "La Belle Époque" before the world quite literally fell apart. We’re talking about the transition from the "S-bend" corset—which made women look like pigeons—to a more vertical, tubular silhouette. It was the year of the "Hobble Skirt." It was the year Paul Poiret and Lucile (Lady Duff-Gordon) were the absolute rockstars of the textile world.

The vibe was changing. Fast.

The Death of the S-Bend and the Rise of the Empire Waist

For years, the "S-bend" corset was the law of the land. It pushed the bust forward and the hips back, creating a shape that looked painful because it actually was. But by 1912, the silhouette started to straighten out. We call it the "Empire" or "Directoire" revival.

Basically, the waistline moved up. Way up. Sometimes it sat just under the bust. This wasn't just a style choice; it was a rebellion against the heavy, multi-layered petticoats of the previous decade. Fashion historian James Laver noted that this era was defined by a desire for a "classical" look, drawing inspiration from ancient Greece, though filtered through a very Edwardian lens.

You’ve got to imagine the sheer weight of these clothes. Even as they got "lighter," a formal 1912 evening gown could still weigh ten pounds or more with all the beadwork and silk. Designers like Paul Poiret claimed he "freed the bust," but honestly? He just traded one kind of restriction for another. He hated corsets, sure, but then he gave the world the hobble skirt.

That Ridiculous, Iconic Hobble Skirt

If you want to understand 1912 fashion for women, you have to talk about the hobble skirt. It’s exactly what it sounds like. The hem was so narrow that women could only take tiny, six-inch steps.

It was a literal hazard.

There are actual news reports from 1912 of women falling into canals or being unable to run from runaway carriages because their skirts were too tight at the ankles. One famous incident involved a woman at a horse race who couldn't step over a small puddle. It was absurd. Yet, it was the height of chic.

Why? Because it looked sleek. It broke away from the "bell" shape of the 1800s. To keep the skirt from ripping, many women wore a "fetter," which was basically a piece of braid or a strap that tied the legs together. Imagine paying a fortune to be physically restrained by your own outfit. Fashion is weird.

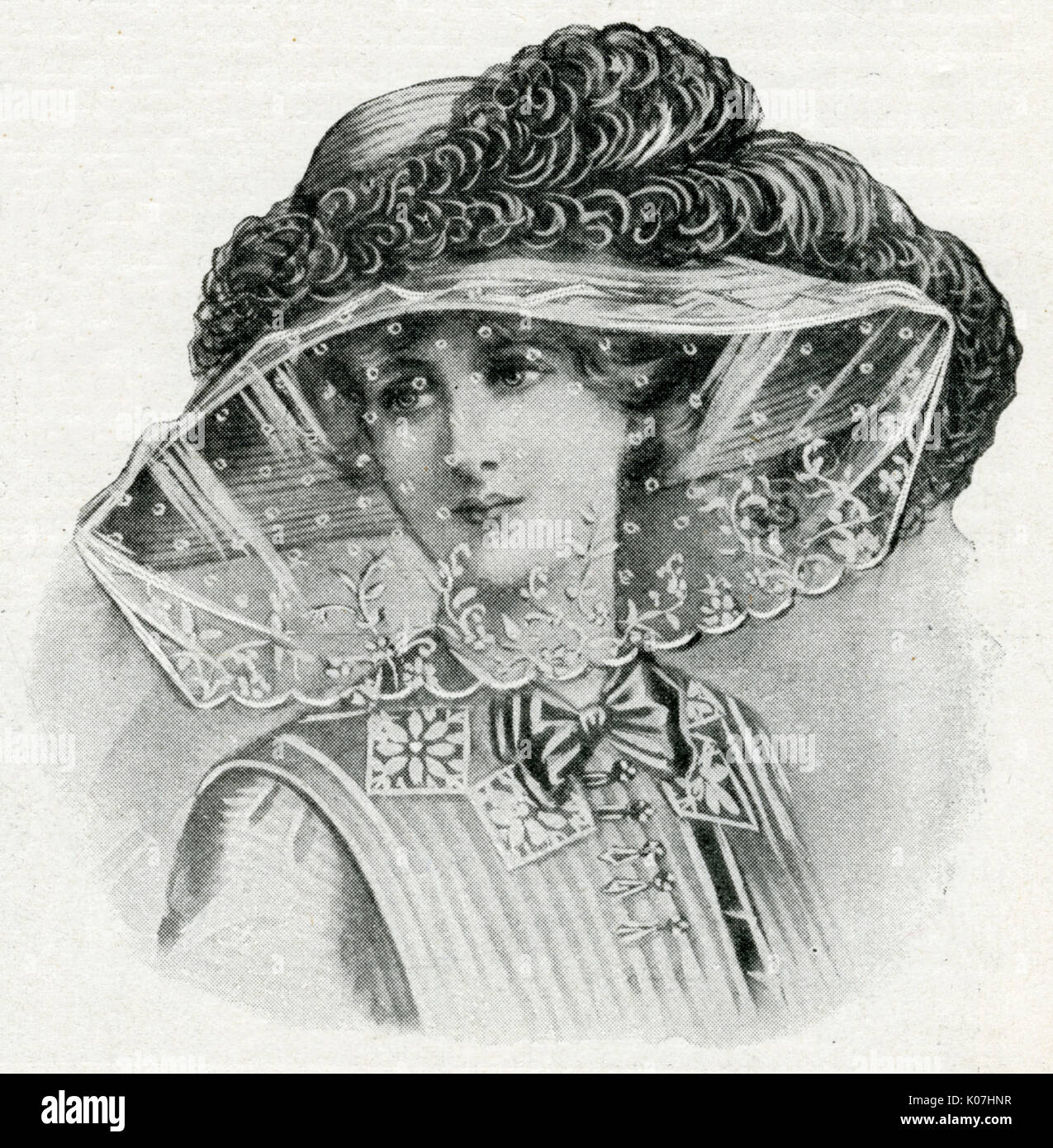

Hats That Could Take an Eye Out

The hats of 1912 were massive. Huge. Monumental. They were called "Merry Widow" hats, named after the operetta, and they were often wider than the wearer's shoulders.

They weren't just big; they were ecosystems. They featured:

- Ostrich plumes (sometimes three or four feet long).

- Entire taxidermied birds (until the Audubon Society rightfully got mad).

- Silk flowers, wax fruit, and yards of tulle.

To keep these monstrosities on, women used "hatpins." These weren't the tiny pins we use today. These were ten-inch steel spikes. In 1912, there was actually a bit of a moral panic about hatpins. Men were terrified of getting stabbed in crowded elevators or streetcars. Some cities even passed laws requiring "protectors" on the ends of pins so women wouldn't accidentally (or purposefully) skewer anyone.

The Titanic Influence and the Lucile Aesthetic

When we talk about 1912, we have to mention Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, known professionally as Lucile. She survived the Titanic, but her influence on 1912 fashion for women was already set in stone before she ever stepped on that boat.

Lucile was the first "celebrity" designer. She gave her dresses names like "Happiness" or "The Sigh of a Distant Sea." She pioneered the "mannequin parade," which we now call a fashion show. Her style was all about layers. She would layer different colors of chiffon—maybe a pale purple over a soft green—to create a "shot" effect that changed as the woman moved. It was ethereal. It was delicate. It was the absolute opposite of the heavy, structured wool suits women wore for traveling.

The contrast was sharp. By day, a woman was encased in a stiff, high-collared "tailor-made" suit. By night, she was a floating cloud of silk and lace.

Fabrics, Colors, and the "Orientalism" Craze

1912 was obsessed with "The East." Thanks to the Ballets Russes performing in Paris, everyone went crazy for "Orientalist" details.

- Kimono sleeves: Wide, comfortable sleeves that didn't require the tight armholes of the Victorian era.

- Harem pants: Poiret tried to make these happen. They didn't really take off for the average woman, but the daring "bright young things" wore them to private parties.

- Bold colors: Instead of just pastels, you started seeing "electric" blue, cherry red, and deep purples.

Satin was the king of fabrics. Specifically, "charmeuse," which had a beautiful drape and a soft sheen. If you were wealthy in 1912, you were wearing silk charmeuse. If you weren't, you were wearing "mercerized" cotton, which was treated to look like silk but felt a lot more like, well, cotton.

What Most People Get Wrong About 1912

A lot of people think everyone in 1912 looked like a princess. They didn't.

For the working class, 1912 fashion for women was a lot more practical, but still restrictive. A shop girl or a factory worker wouldn't be wearing a hobble skirt; she'd be wearing a "walking skirt" that cleared the ground by an inch or two. No one wanted to drag their hem through the literal filth of a 1912 city street.

✨ Don't miss: Growing Out Short Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About the In-Between Phase

Also, the "unbound" look Poiret championed? It was a lie. Even if a woman didn't wear a heavy, boned corset, she was wearing a "brassiere" (a term that was just starting to gain traction) and a long-line girdle to keep her hips smooth. The "natural" look took a lot of work to maintain.

Practical Insights for History Buffs and Costumers

If you’re looking to recreate this look or just understand the era's vibe, keep these specific 1912 hallmarks in mind:

- The Silhouette: It’s a "V" or a "Y" shape. Wide at the top (hat and shoulders) and narrowing down to the ankles.

- The Footwear: High-button boots or pumps with a "Louis" heel (slightly curved). Stockings were usually black silk or wool, regardless of the dress color.

- The Hair: "Pompadour" style. It was puffed out over wire frames called "rats." If you see a woman with "big" hair in 1912, she’s almost certainly wearing someone else's hair mixed in with her own.

- The Accessories: Handbags were small—usually beaded "reticules." Long "lavalier" necklaces were the jewelry of choice, hanging down to the mid-chest.

1912 was the last gasp of a certain kind of luxury. Within two years, World War I would break out, and the flamboyant plumes, the restrictive skirts, and the obsession with "Lady-like" delicacy would vanish. Women would head into factories, their skirts would rise to the mid-calf for safety, and the "Merry Widow" hats would be boxed up forever.

To really dive into this, check out the digital archives of The Delineator or Vogue from 1912. The illustrations show a world that knew it was changing but didn't know how fast the floor was about to drop out. You can also visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute online database; they have several Poiret and Lucile pieces from this exact year that show the intricate beadwork you can't see in grainy black-and-white photos.

Study the construction of the "internal waistband." Most 1912 dresses weren't one piece; they were built on a structured inner belt that took the weight of the skirt off the shoulders. It’s a genius bit of engineering that modern fast fashion has completely abandoned. If you're sewing a replica, start with that inner "petersham" ribbon—it's the secret to making the whole outfit sit correctly without sagging.