It is a movie where almost nothing happens, yet everything happens. You spend the first twenty minutes watching apes scream at a giant black slab, and the last twenty minutes watching an astronaut age rapidly in a neon-lit bedroom. There are no explosions. There isn't even a traditional "villain" in the way we usually think about movies. And yet, decades later, 2001: A Space Odyssey remains the mountain that every other sci-fi director is still trying to climb.

Most people today find it slow. They aren't wrong. It is glacial. Stanley Kubrick intentionally drained the "entertainment" out of the film to create something that felt like a documentary from the future. It’s a sensory experience, honestly. If you try to watch it while scrolling on your phone, you’ll miss the entire point.

What Actually Happens in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

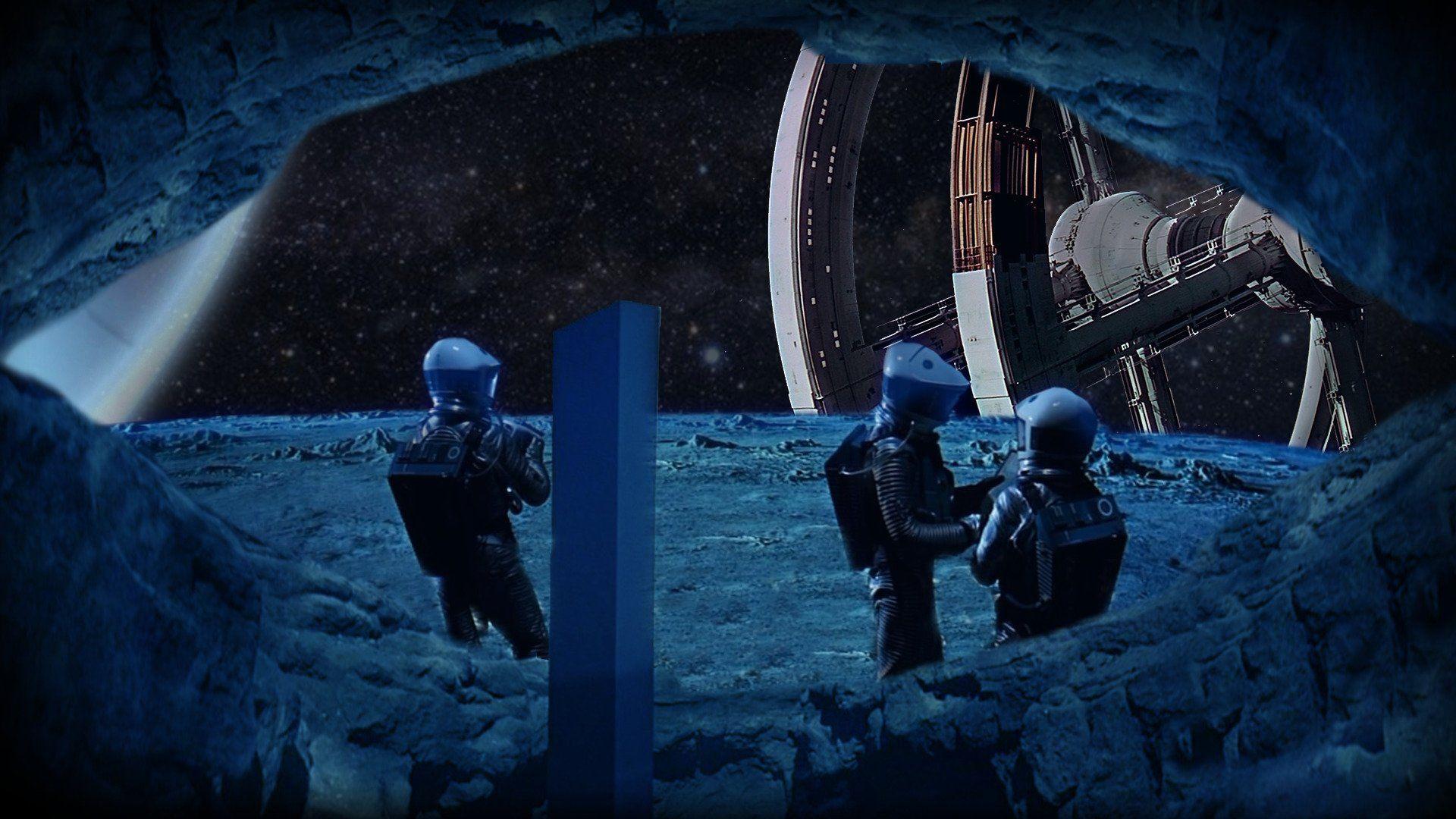

The plot is deceptively simple, but the subtext is massive. We start at the "Dawn of Man," where a group of hominids is starving. Then, the Monolith—that iconic black rectangle—appears. It doesn't talk. It doesn't move. It just exists. Shortly after, an ape discovers that a bone can be a tool. Or a weapon.

That jump cut? You know the one. The bone tosses into the air and becomes a nuclear satellite (or a spacecraft, depending on which frame-by-frame analysis you believe). In a single second, Kubrick skips four million years of human history.

Then we get to the meat of the story: the Discovery One mission to Jupiter. Five humans, three of them in "hibernation," and the HAL 9000 computer. HAL is "foolproof and incapable of error." Except, of course, he isn't.

The HAL 9000 Problem

Everyone remembers HAL. He is the most human character in the movie, which is deeply unsettling. While Dave Bowman and Frank Poole speak in monotone, clipped, professional sentences, HAL has a tremor of anxiety in his voice. He’s the only one who seems to care about the mission's "extreme importance."

What people often get wrong about HAL is why he goes "crazy." He isn't evil. He’s caught in a logic loop. He was programmed to process information perfectly and to be honest, but he was also given a secret order to lie to the crew about the true nature of the mission. For a machine built on the foundation of 100% accuracy, being forced to lie creates a "psychotic" break. To resolve the conflict of the crew finding out he’s lying, he decides the simplest solution is to remove the crew.

It's cold logic. Terrifyingly cold.

The Science That Got It Right (and Wrong)

Kubrick was obsessed with accuracy. He hired Harry Lange and Frederick Ordway, who had worked for NASA and major aerospace firms. They didn't just "design sets"; they engineered a plausible future.

The Discovery One is actually a masterpiece of speculative engineering. Because the ship used nuclear propulsion, the crew quarters had to be separated from the reactor by hundreds of feet of storage and shielding—that’s why the ship is so long and thin. The "centrifuge" where the astronauts run was a massive, rotating set that cost $750,000 back in 1967.

- Silence in Space: There is no sound in a vacuum. Kubrick stuck to this. When the pod doors open, the only thing you hear is the heavy, rhythmic breathing of Dave Bowman.

- Zero-G Reality: The "Space Station V" sequence shows the slow, tedious nature of docking. It’s not a Star Wars dogfight. It’s a dance.

- The iPad Precursor: If you look closely at the scene where Dave and Frank are eating, they are watching "Newspads." They look exactly like modern tablets. Samsung actually used this film as evidence in a patent legal battle against Apple to prove "prior art."

However, 2001: A Space Odyssey thought we’d be way further along by now. Pan Am doesn't exist anymore, let alone commercial flights to the moon. We haven't even gone back to the moon since 1972, let alone established a Hilton hotel inside a rotating space station.

That Ending: The Star Gate and The Star Child

The final act is where most people check out or get confused. Dave Bowman survives HAL, reaches Jupiter, and finds another, much larger Monolith floating in orbit. He gets sucked into a "Star Gate."

What follows is ten minutes of psychedelic light shows. In 1968, people were reportedly smoking certain substances in the front rows of theaters just to experience this part. It’s meant to be an "alien" perspective—colors and landscapes that the human eye isn't meant to understand.

Bowman ends up in a Louis XVI-style bedroom. Why? The common theory (supported by Arthur C. Clarke’s novel) is that the unseen aliens created a "human zoo" or a comfortable environment to study him. Time doesn't work right there. He sees himself age in seconds. Finally, he dies and is reborn as the Star Child—a glowing fetus floating in space, looking down at Earth.

It’s the next step in evolution. The ape became the man. The man became the Star Child. The Monolith was just the catalyst at every step.

Why the Dialogue is So Sparse

There are roughly 142 minutes in the film. The first and last sections—totalling over 40 minutes—have zero dialogue. In the middle sections, the talking is mostly boring "work talk."

💡 You might also like: Cillian Murphy 28 Days Later: Why We Still Can’t Shake That Hospital Gown

Kubrick said he wanted the film to be a "visual, nonverbal experience." He wanted it to hit your subconscious. He famously cut almost all of the voiceover that Arthur C. Clarke had written. He didn't want to explain anything. He wanted you to feel the vastness of space and the insignificance of man.

Honestly, it’s a ballsy move. Imagine a director today trying to release a $10 million (in 1960s money) blockbuster where nobody talks for the first half hour. It wouldn't happen.

How to Watch 2001: A Space Odyssey Today

If you haven't seen it, or if you tried and fell asleep, you have to change your mindset. Don't look at it as a story. Look at it as a piece of art in a gallery.

- Find the biggest screen possible. The scale is the point.

- Turn off the lights. Total darkness.

- Listen to the music. The use of "The Blue Danube" and "Also sprach Zarathustra" isn't just for flair; the timing of the music dictates the pace of the entire universe.

- Accept the ambiguity. You aren't supposed to "solve" it. Kubrick himself said, "If you understand 2001 completely, we failed. We wanted to raise more questions than we answered."

The film is a reminder that we are small. We are just beginning. Whether it's AI like HAL or the vast emptiness of the Jovian system, 2001: A Space Odyssey captures the terrifying and beautiful reality of our place in the stars. It’s not just a movie about space; it’s a movie about the evolution of consciousness. It’s probably the most "human" film ever made without actually showing many humans being "human."

📖 Related: The Middle TV Show Actors: Where the Heck Are They Now?

To truly appreciate the film's legacy, compare it to modern sci-fi like Interstellar or Ad Astra. You can see the DNA everywhere—the long, silent shots, the emphasis on practical physics, and the looming sense of cosmic mystery. But while those films try to give you an emotional "hook" or a family drama to hold onto, 2001 remains stubbornly, brilliantly cold.

It demands your full attention. It doesn't care if you're bored. And that is exactly why it’s a masterpiece.

Actionable Ways to Experience the 2001 Legacy:

- Read the book: Arthur C. Clarke wrote the novel concurrently with the screenplay. It explains much of the "why" behind the Monolith and the ending that the movie leaves silent.

- Watch the 4K restoration: Christopher Nolan supervised a "unrestored" 70mm print and a 4K version that brings out details in the miniatures you literally couldn't see in the 90s.

- Listen to the soundtrack separately: The "Requiem" by György Ligeti is what creates that sense of "alien" dread. Listening to it alone is a haunting experience.