You’ve probably seen a diagram of the esophagus in a high school biology textbook. It usually looks like a simple, straight pink tube connecting the throat to the stomach. Boring, right?

Honestly, that’s a massive oversimplification.

Your esophagus isn’t just a passive slide for a cheeseburger. It’s a highly coordinated, muscular powerhouse that uses a sophisticated relay of nerves and sphincters to keep you from choking or burning your throat with acid. If you’ve ever felt like food was "stuck" in your chest or dealt with the searing heat of GERD, you know exactly how complex this 25-centimeter organ really is.

What the Standard Diagram of the Esophagus Usually Misses

Most diagrams show a hollow pipe. In reality, the esophagus is collapsed when it's empty. It only expands when you swallow.

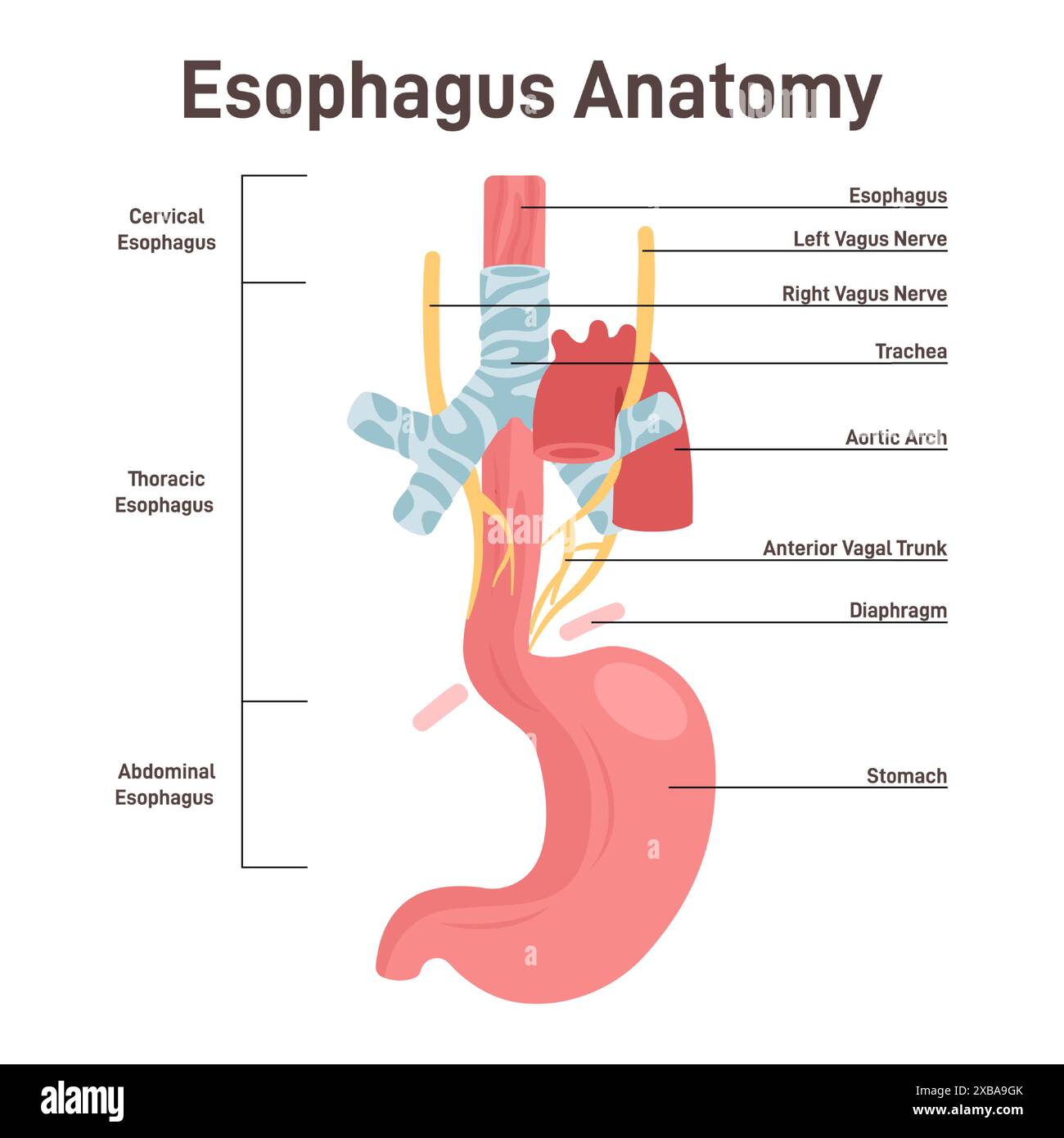

It starts at the lower end of the pharynx—right behind the windpipe (trachea)—and travels down through the "thoracic cavity," eventually piercing the diaphragm to meet the stomach. It’s not just sitting there loosely. It's tucked neatly between the spine and the heart.

The Three Narrowings

If you look closely at a detailed medical diagram of the esophagus, you’ll notice it isn't perfectly uniform. There are three specific spots where the tube naturally constricts. Surgeons and gastroenterologists obsess over these because they are the most common places for a stray fish bone or a pill to get stuck.

- The Cervical Constriction: This is at the very top, near the cricoid cartilage. It’s the "gatekeeper."

- The Thoracic Constriction: Here, the esophagus gets squeezed slightly by the arch of the aorta and the left main bronchus.

- The Phrenic Constriction: This is the literal hole in the diaphragm (the hiatus) where the esophagus passes into the abdomen.

Layers of the Wall: It’s Not Just One Thick Muscle

If you were to take a cross-section of a diagram of the esophagus, you'd see four distinct layers. This is where the magic happens.

First, there’s the Mucosa. This is the innermost lining, made of stratified squamous epithelium. It’s tough. It has to be. Think about the last time you ate a sharp tortilla chip without chewing it enough. That mucosa is designed to handle the friction.

Underneath that is the Submucosa. This layer contains the mucous glands that keep everything lubricated. It also houses the Meissner’s plexus, a network of nerves that tells the body, "Hey, food is coming!"

🔗 Read more: What to Take to Gain Weight: Why Your Bulking Shake Isn't Working

Then comes the Muscularis Externa. This is where things get weird. The top third of your esophagus is skeletal muscle—the kind you can control. That’s why you can consciously decide to swallow. The bottom third is smooth muscle, which is involuntary. The middle third? It’s a chaotic mix of both. Once food hits that middle section, you’ve lost all manual control. The body takes over.

Finally, there’s the Adventitia. Unlike the stomach, which is wrapped in a slippery "serosa," the esophagus is held in place by loose connective tissue. This is a big deal in oncology; because it lacks a serosal layer, esophageal cancer can unfortunately spread to nearby organs more easily than some other digestive cancers.

The Sphincters: The Body’s Security Guards

You can't talk about a diagram of the esophagus without mentioning the bookends: the Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES) and the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES).

The UES is under your control, mostly. It keeps air from rushing into your stomach when you breathe.

The LES is the real troublemaker. It's not a "true" anatomical sphincter like the one at the exit of your stomach; it’s more of a physiological high-pressure zone. It stays shut to keep stomach acid where it belongs. When it fails, you get Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD).

📖 Related: Calm Meditation for Anxiety: Why Your Brain Won't Shut Up and How to Fix It

The Z-Line Mystery

In a clinical diagram of the esophagus, doctors look for the "Z-line." This is the jagged junction where the pale, tough esophageal lining meets the dark red, glandular lining of the stomach. If this line moves too far up, it’s a sign of Barrett’s Esophagus—a condition where the body starts replacing esophageal cells with stomach-like cells because of chronic acid damage. It’s basically the body’s way of trying to "armor" itself against the burn, but it increases the risk of cancer.

How Swallowing Actually Works (Peristalsis)

Swallowing is a three-stage process. You have the oral phase (chewing), the pharyngeal phase (the "gulp"), and the esophageal phase.

When food enters the esophagus, a wave of muscular contractions called primary peristalsis begins. It’s like squeezing a tube of toothpaste from the bottom up. Even if you were hanging upside down, you could still swallow. Gravity helps, but it isn't the boss.

If a piece of food gets stuck, the esophagus senses the stretch and triggers secondary peristalsis. This is a localized, forceful "clearing wave" that tries to push the blockage down without you even realizing it’s happening.

Common Misconceptions About Esophageal Health

Most people think "heartburn" has something to do with the heart. It doesn't. It's just that the esophagus runs right behind the heart, and the nerves in that area are a bit "noisy." Your brain sometimes can't tell if the pain is coming from your cardiac muscle or your esophageal lining.

Another big one: "I have a small throat."

Usually, people who feel they have a "small throat" actually have an issue with esophageal motility (the way the muscles move) or a narrowing like an "Schatzki ring." It’s rarely about the actual size of the tube and more about the mechanics of the pump.

🔗 Read more: Are Sushi Rolls Healthy? The Honest Truth About What You’re Actually Eating

Visualizing the Problems: When the Diagram Changes

When things go wrong, the diagram of the esophagus changes shape.

- Hiatal Hernia: This is when the top of the stomach actually pokes up through the diaphragm into the chest. It ruins the LES pressure and makes reflux inevitable.

- Achalasia: The LES refuses to open. The esophagus becomes dilated and "mega-esophagus" occurs, where the tube stretches out like a balloon because food can't get into the stomach.

- Esophageal Varices: These are swollen veins in the lining, often caused by liver disease. On a diagram, they look like blue, bulging grapes. If they burst, it’s a medical emergency.

Actionable Steps for Esophageal Health

Understanding the anatomy is cool, but keeping the tube functional is better.

Stop eating three hours before bed. Remember that LES we talked about? It’s weaker when you’re lying down. Give your stomach time to empty so there’s no pressure on that sphincter while you sleep.

Watch the "trigger" foods. Caffeine, chocolate, and peppermint actually relax the LES. If you’re prone to reflux, you’re basically telling the security guard to take a nap.

Chew more than you think you need to. The esophagus is tough, but it’s not a blender. Reducing the mechanical stress on the mucosa prevents the tiny micro-tears that can lead to inflammation over decades.

Manage your weight. Abdominal fat puts physical pressure on the stomach, which forces the LES open. It’s a simple mechanical issue.

If you're looking at a diagram of the esophagus because you’re having trouble swallowing (dysphagia) or persistent pain, don’t ignore it. The lining is resilient, but it isn't invincible. Chronic inflammation can lead to strictures—permanent scarring that narrows the path. Modern treatments like "dilation" (where a doctor literally stretches the tube back out) or PPI medications can manage these issues, but early intervention is the only way to keep the Z-line where it belongs.

The esophagus is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. It's a high-speed transit system that operates in a high-pressure, high-acid environment every single day. Treat it with a little respect.