Honestly, the first few years of parenthood feel like a blur of diapers, sleepless nights, and a seemingly endless string of pediatrician appointments. You walk in, your kid gets poked, they cry for a minute, you get a sticker, and you head home. But if you’re trying to keep track of the actual list of vaccines for children by age, it gets confusing fast. Why does a two-month-old need six different things? Why do some shots require four doses while others only need one?

It's a lot.

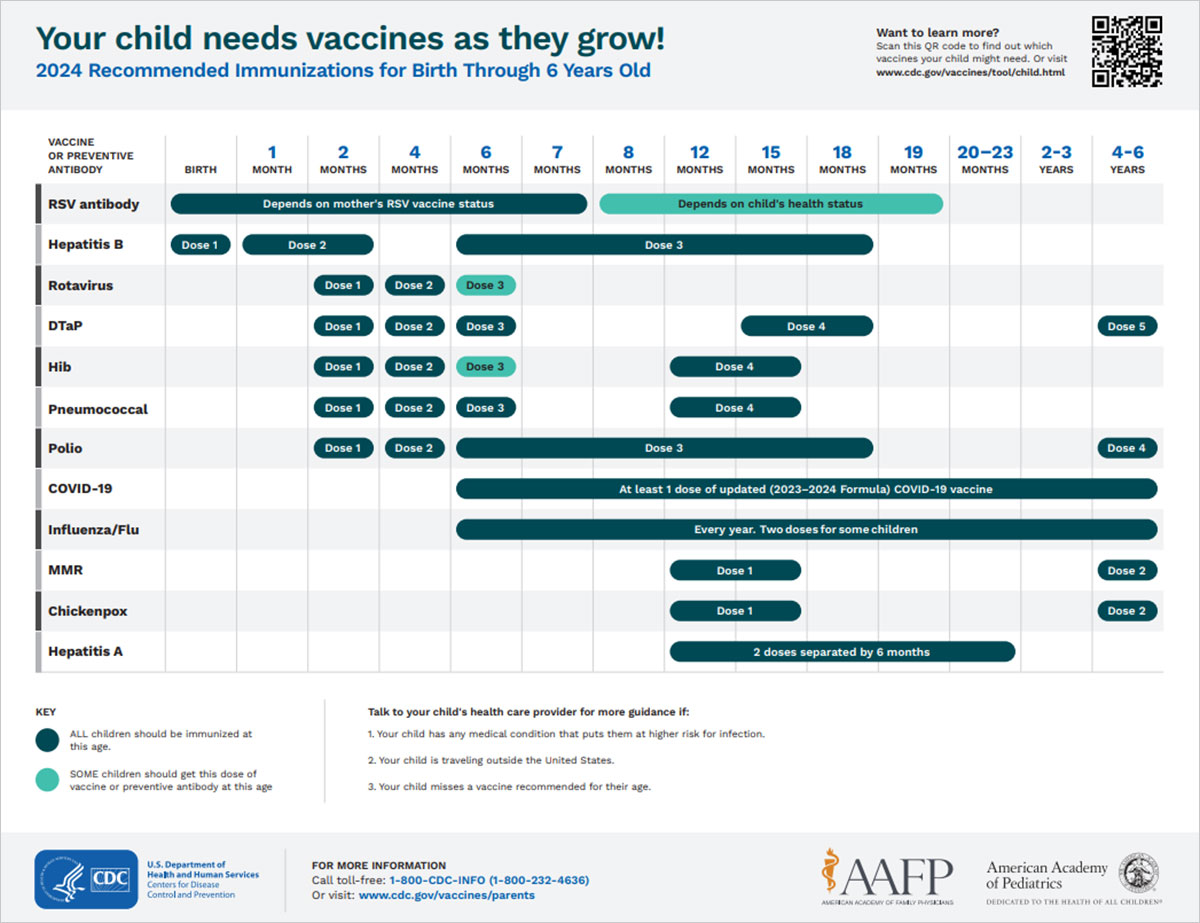

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) update the schedule every year, and while it looks like a chaotic spreadsheet at first glance, there’s a very specific logic to the timing. It’s all about the "window of vulnerability." Babies are born with some maternal antibodies—basically a temporary immune shield from their mom—but that wears off quickly. We vaccinate when we do because that’s the earliest point a child’s immune system can safely learn to defend itself before they run into the "wild" versions of these germs.

The Newborn Phase: Starting at Day One

Most people are surprised that the list of vaccines for children by age actually starts before you even leave the hospital.

The Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine is the outlier. It’s usually given within 24 hours of birth. You might wonder why a newborn needs protection against a virus often associated with adult behaviors, but HepB is incredibly hardy. It can live on surfaces for a week. For a tiny baby, contracting Hepatitis B carries a 90% risk of it becoming a chronic, lifelong infection that leads to liver cancer or cirrhosis. Giving that first dose at birth acts as a safety net.

If the mom happens to be an asymptomatic carrier of HepB and doesn't know it, that birth dose is a literal lifesaver.

The "Infant Gauntlet": 2, 4, and 6 Months

This is the stretch that hits parents the hardest. It feels like a lot of needles. However, many clinics use combination shots like Pediarix or Vaxelis to reduce the total number of pokes.

At the two-month mark, the heavy hitters come out. You’ve got Rotavirus (RV), which is actually an oral liquid, not a shot. It prevents that brutal diarrheal illness that used to send thousands of babies to the ER for dehydration every winter. Then there’s DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and acellular Pertussis). Pertussis, or whooping cough, is the big concern here. To an adult, it’s a nagging cough; to a two-month-old, it can stop their breathing entirely.

You’ll also see Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b). Before this vaccine existed in the 1980s, Hib was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in kids under five. It’s a terrifying disease that can cause permanent brain damage in hours. Rounding out the list are PCV15 or PCV20 (Pneumococcal) and IPV (Polio).

Guess what? You do almost all of that again at four months.

💡 You might also like: Butt implants gone wrong: What the glossy brochures don’t tell you

And again at six months.

The reason for the repetition is simple: "priming" the immune system. One dose might give some protection, but the second and third doses act like "booster" shots that lock that memory into the child's immune cells. By six months, your baby is also eligible for their first Influenza (flu) shot, which is vital because infants have the highest rates of flu-related hospitalizations outside of the elderly. During the 2023-2024 season, the CDC reported that the majority of pediatric flu deaths occurred in children who were not fully vaccinated.

The Toddler Transition: 12 to 18 Months

Once you hit the first birthday, the list of vaccines for children by age shifts toward live-attenuated vaccines.

This is when kids usually get the MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) and Varicella (Chickenpox) shots. We wait until 12 months for these because those maternal antibodies I mentioned earlier can actually neutralize a live vaccine if given too early, making it ineffective.

Measles is back in the news lately because it is incredibly contagious—one person can infect 12 to 18 others in an unvaccinated population. It’s not just a "rash." It causes "immune amnesia," essentially wiping out the immune system's memory of other diseases the child has already fought off.

During this window, they’ll also get:

- Hepatitis A: Usually given in two doses, six months apart. This protects against a virus often spread through contaminated food or water (or diapers in a daycare setting).

- The DTaP booster: Because that whooping cough protection starts to wane.

- The final Hib and PCV doses: Crossing these off the list for good.

The "Big Kid" Boosters: Ages 4 to 6

Before they head off to kindergarten, children need a final round of "school shots." This is mostly about topping off the immunity they built as babies. They get their second doses of MMR and Varicella, and their fifth dose of DTaP.

It’s a bit of a milestone. After this, you usually get a long break from the frequent needle pokes until the pre-teen years.

The Adolescent Shift: 11 to 12 Years

When kids hit middle school, the list of vaccines for children by age pivots to diseases that become more of a risk as they grow into social, active teenagers.

Tdap is the big one here. It’s a "booster" version of the infant DTaP. It’s particularly important because it prevents teens from catching whooping cough and passing it to infants who are too young to be vaccinated.

Then there is Meningococcal (MenACWY). This protects against four strains of bacterial meningitis. Meningitis outbreaks are rare but catastrophic, often spreading in high schools, locker rooms, and college dorms.

Finally, there’s HPV (Human Papillomavirus). This is one of the few vaccines we have that actually prevents cancer—specifically cervical, anal, and throat cancers. The medical community, including experts like Dr. Peter Hotez, emphasizes that giving it at age 11 or 12 creates a much stronger immune response than giving it later in the teens. It’s a "pre-exposure" vaccine; you want the protection there long before they ever encounter the virus.

📖 Related: Why looking at pictures of self harm is a cycle you need to break

Why the Timing Matters So Much

Some parents ask about "spacing out" the vaccines. It sounds logical—"let's not overwhelm the system"—but the data doesn't really support it.

Dr. Paul Offit, a leading virologist at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, often points out that a baby's immune system handles thousands of "challenges" (bacteria and viruses) every single day just by crawling on the floor or sticking a toy in their mouth. The total number of antigens in the entire modern childhood vaccine schedule is actually lower than it was in the 1980s, even though we protect against more diseases now, because the shots are more refined.

Spacing them out just leaves a child unprotected for a longer period. It’s like wearing a seatbelt only half the time you're in a car.

Actionable Steps for Parents

Managing a list of vaccines for children by age doesn't have to be a logistical nightmare.

1. Use the Digital Portal

Most pediatric offices now use an online portal (like MyChart). Don't rely on the yellow paper card; those get lost in a move or a flooded basement. Ensure your clinic has uploaded everything so you can download a PDF for school registration or summer camp in two clicks.

2. Prep for the "Post-Shot Slump"

Expect a low-grade fever or some crankiness for 24-48 hours after the 2-month and 12-month visits. This isn't the vaccine "making them sick"; it's the immune system doing its "workout." Have infant acetaminophen (Tylenol) on hand, but check with your doctor for the correct dosage based on your child's current weight, not their age.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Most Healthy Oil to Cook With: What Most People Get Wrong

3. Address the Pain Directly

For older kids, don't lie and say "it won't hurt." It’s a needle; it stings. Instead, use a "Buzzy" (a vibrating device that numbs the area) or a "ShotBlocker." Distraction works wonders—let them watch a video or use a sugary snack as a reward immediately after.

4. Keep a Side Effect Diary

If your child has a localized reaction—like a large red lump at the injection site—take a photo. Show it to the doctor at the next visit. Most of the time it's a normal "Arthus reaction," but having a visual record helps the doctor decide if they should use a different brand or site next time.

Vaccination is a foundational part of modern preventative medicine. By staying on top of the schedule, you aren't just checking boxes for school—you're providing a biological "instruction manual" that helps your child's body recognize and defeat dangerous pathogens before they ever have a chance to cause harm.