Winnie the Pooh is everywhere. You see him on diapers, expensive porcelain figurines, and those weirdly aggressive bumper stickers. He is the face of childhood innocence, a "silly old bear" who just wants a bit of honey. But if you look at the actual life of A.A. Milne, the man who brought him into the world, the story isn't nearly as fuzzy as a Disney plush. It’s actually kinda heartbreaking.

Alan Alexander Milne didn't want to be the "Pooh guy." Before the bear, he was a serious playwright and a contributor to Punch magazine. He was a veteran of World War I—an experience that likely shaped the quiet, safe, trauma-free world of the Hundred Acre Wood. He wanted to be known for his wit and his political essays. Instead, he wrote four thin books for his son, Christopher Robin Milne, and the world decided that was the only thing he was allowed to be.

📖 Related: Why The Middle Season Finale Still Hits Harder Than Most Sitcom Send-offs

Why A.A. Milne and Winnie the Pooh Became a Cultural Phenomenon

The magic started with a real bear named Winnipeg. During the First World War, a Canadian soldier bought a black bear cub and eventually gave it to the London Zoo. Milne’s son, Christopher Robin, became obsessed with her. He even named his own stuffed swan "Pooh." You combine those two, and you get the name that has dominated nurseries for a century.

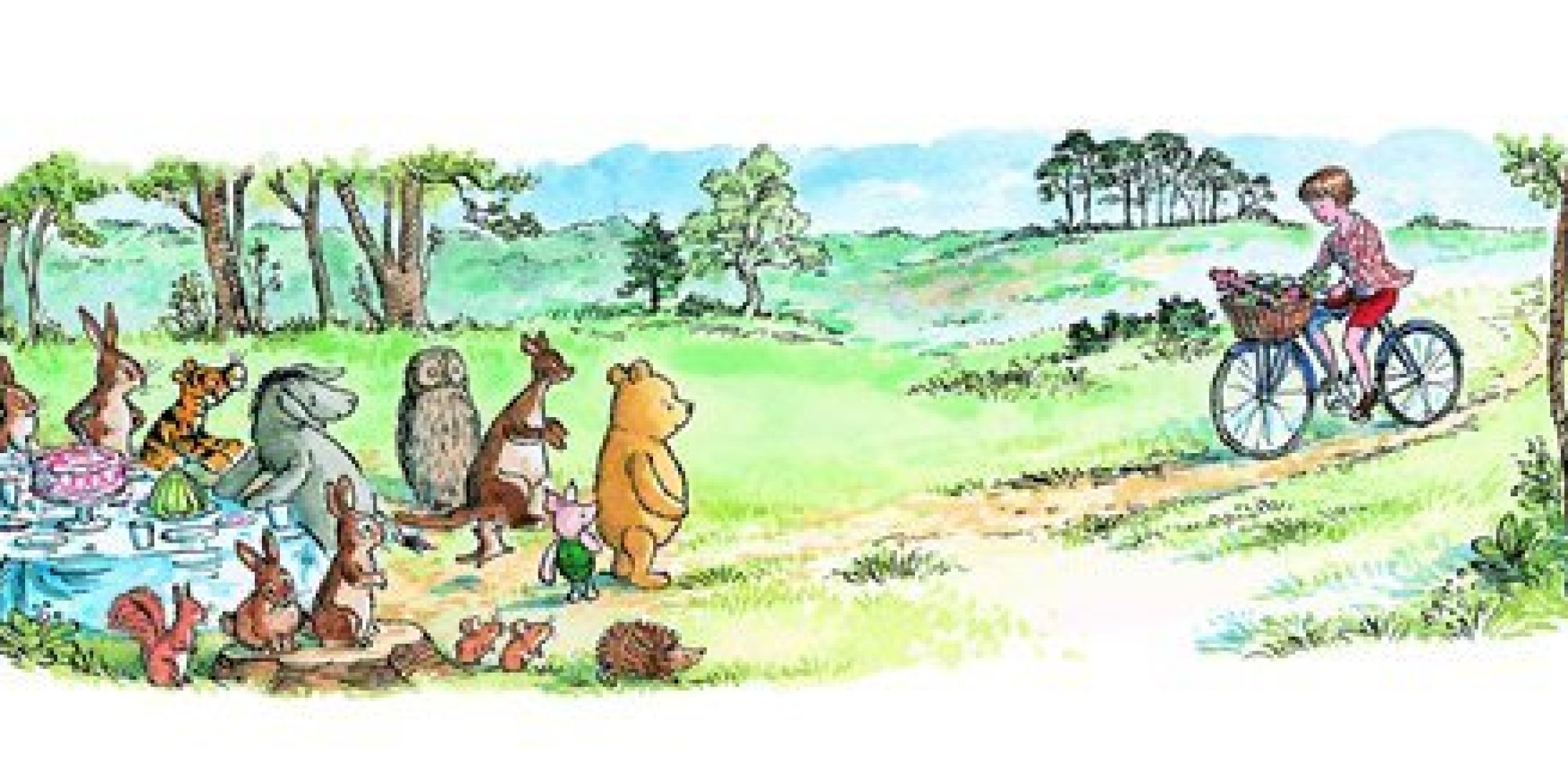

People think these stories are just for kids. They aren't. Not really. Milne had this incredible ability to capture the specific, high-strung anxieties of adulthood and hide them in a donkey or a tiny pig. Eeyore isn't just "sad." He’s a clinical study in depression, yet he is completely accepted by his friends. They don't try to "fix" him. They just invite him along. That’s deep.

The Real People Behind the Pages

Christopher Robin wasn’t just a character. He was a real boy, and having his childhood sold to the masses wasn't a great experience. Imagine growing up and realizing your private play sessions are being read by millions of strangers. It created a massive rift between father and son. Christopher later wrote in his memoirs that his father had "got to where he was by climbing on my infant shoulders."

- Ernest H. Shepard: The illustrator who actually modeled the drawings on his own son’s bear, Growler, not the original Winnie.

- Daphne Milne: A.A. Milne’s wife, who was the one who actually provided much of the creative spark for the characters during playtime.

- The Stuffed Toys: They are real. You can see the original Tigger, Kanga, Eeyore, and Pooh at the New York Public Library today. They look a bit worn out, honestly, but they’re the literal DNA of this entire franchise.

The Philosophical Depth You Probably Missed

There is this idea in Taoism called "The Uncarved Block," or Pu. Basically, it's about being in your natural state without trying to be something else. Pooh is the ultimate Uncarved Block. He doesn't overthink. He just is.

Compare that to Rabbit, who is always busy doing nothing, or Owl, who pretends to be much smarter than he actually is (he can’t even spell "Tuesday"). Milne was low-key roasting the self-important intellectuals of his time. He was saying that the simplest person in the room is often the only one who actually knows what’s going on.

It's weirdly profound.

We live in a world that demands 24/7 productivity. Milne created a space where the most important thing you could do was go on an "Expotition" to the North Pole or check a honey pot. It’s an escape from the noise.

The Messy Legal Battle and the Disney Takeover

A.A. Milne died in 1956. By then, he had grown to almost resent the bear. He felt it overshadowed his "serious" work, which it absolutely did. But the real shift happened in the 1960s when Walt Disney stepped in.

Disney didn't just buy a character; they bought a lifestyle. They added the red shirt. They gave him the American accent. They turned the Hundred Acre Wood into a multi-billion dollar merchandising machine. Some purists hate it. They think the original sketches by E.H. Shepard have a soul that the bright yellow Disney version lacks.

The rights situation was a nightmare for decades. There were lawsuits between the Stephen Slesinger estate (who bought US rights in the 30s) and Disney that lasted longer than most marriages. It’s ironic, honestly. A book about a bear who doesn’t care about "stuff" became the center of one of the greediest legal battles in Hollywood history.

The Public Domain Shift

As of January 2022, the original Winnie-the-Pooh book entered the public domain. This is why we suddenly have horror movies like Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey. It’s why you see weird indie projects using the character.

Anyone can use the 1926 version of Pooh now. But—and this is a big "but"—you can't use the red shirt. You can't use Tigger yet (he showed up in the later books). You have to stick to the original Milne and Shepard version. It’s a legal minefield that keeps lawyers very, very happy.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Stories

Most people think Pooh is a "kids' book" in the way Paw Patrol is for kids. It's not. Milne’s writing is sharp. It’s cynical. It’s very British.

When Pooh gets stuck in Rabbit's door because he ate too much, the solution isn't some magical lesson about sharing. It’s Rabbit using Pooh’s legs as a towel rack while they wait for him to get thin again. There’s a certain grit to the original stories that the cartoons softened.

The ending of The House at Pooh Corner is probably the saddest thing ever written in English. Christopher Robin has to go away to school. He has to grow up. He asks Pooh to never forget him, even when he’s a hundred. If you can read that without getting a lump in your throat, you’re probably a robot. It’s a story about the death of childhood. Milne wasn't just writing for his son; he was mourning the fact that his son was growing up and drifting away from him.

How to Actually Experience the Real Pooh Today

If you want to move past the corporate version and see what A.A. Milne was actually talking about, you have to go back to the source. Don't just watch the movies.

- Read the original 1926 text. Pay attention to the punctuation. Milne used capital letters for "Important Things" in a way that perfectly captures how a child thinks.

- Visit Ashdown Forest. This is the real-life Hundred Acre Wood in East Sussex, England. You can play Poohsticks at the actual bridge. It’s surprisingly small in person, which makes sense—the world feels huge when you're five, but it's really just a few acres of trees.

- Look at the Shepard sketches. Notice how much white space there is. There is a loneliness to those drawings that fits the tone of the books perfectly.

A.A. Milne gave the world a gift that he eventually grew to regret. He wanted to be a man of letters, but he became the man of the bear. It’s a reminder that we don’t always get to choose our legacy. Sometimes, the thing you do "just for fun" or for your family is the only thing that really sticks.

The bear survived. He survived the war, he survived the lawsuits, and he survived the horror movie remakes. He’s still there, sitting in a tree, wondering if it's an "eleventy-one" or just a "humming" kind of day.

To truly understand the legacy of A.A. Milne and Winnie the Pooh, start by visiting the original toys at the New York Public Library or taking a walk through a local wooded area without your phone. The goal of Milne's work was never to sell lunchboxes; it was to encourage a specific kind of quiet observation. Sit down, find a "thoughtful spot," and try to see the world through the eyes of someone who isn't worried about the next notification. That is where the real magic of the Hundred Acre Wood lives.