You’ve been there. The sprint planning meeting is dragging into its third hour, everyone is staring at a Jira ticket that says "As a user, I want to reset my password," and the developers are arguing with the product owner about what "reset" actually means. Is it an email link? A temporary code? Does it log them out of all devices? This is where everything falls apart. If you don't nail the acceptance criteria for user stories, you aren't just looking at a minor misunderstanding; you're looking at wasted salary, missed deadlines, and a product that makes users want to throw their laptops across the room.

The truth is that most teams treat these criteria like an afterthought. They scribble a few bullet points five minutes before the sprint starts and call it a day. That’s a mistake.

Why We Fail at Acceptance Criteria

Software development is basically a giant game of Telephone. The customer tells the stakeholder what they want, the stakeholder tells the product manager, the product manager writes a user story, and the developer builds what they think the story meant. By the time it reaches the QA engineer, the original intent is long gone. Acceptance criteria for user stories act as the guardrails. They define the "boundaries" of a feature. Without them, scope creep isn't just a risk—it's a mathematical certainty.

I’ve seen projects where "simple" login features ballooned into three-week nightmares because nobody specified that the system needed to handle international phone numbers. It’s painful.

Honestly, the problem usually stems from a lack of shared context. Bill Wake, who famously created the INVEST mnemonic (Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Small, Testable), argued that stories are "a promise for a conversation." But conversations are forgotten. Acceptance criteria (AC) are the written record of that conversation. They are the "Done-Done" definition for a specific piece of work.

The Difference Between "The Story" and "The Criteria"

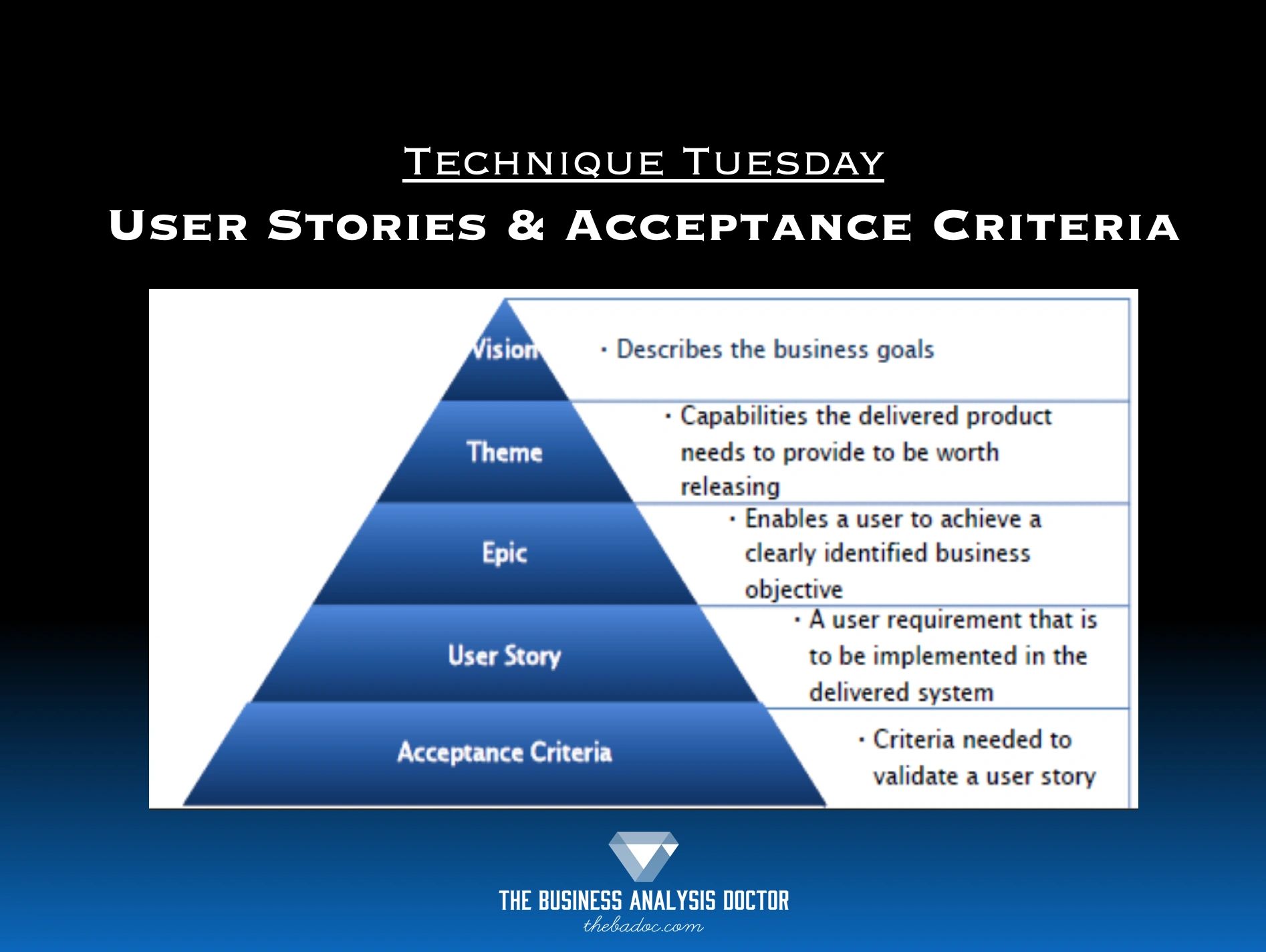

Think of the user story as the intent and the acceptance criteria as the evidence.

The story is the "why" and the "who." For example: As a frequent traveler, I want to save my credit card details so I can book flights faster. That’s great for empathy, but it’s useless for a coder. The coder needs to know the specifics. Does it support AMEX? Can the user save more than one card? What happens if the card expires tomorrow?

The acceptance criteria for user stories should answer those nagging "what if" questions. They aren't technical specifications—you shouldn't be telling the dev to use a specific SQL query—but they must be functional requirements that any human can verify.

Two Ways to Write Them (And Why One Is Winning)

There isn't just one way to write these, and sticking to a rigid template is usually a bad move. However, two main styles dominate the industry right now.

1. The Checklist (Rule-Based)

This is the old-school, straightforward way. It’s basically a list of conditions that must be true.

- User cannot submit the form without an @ symbol in the email field.

- Password must be at least 8 characters.

- Error message "Invalid Credentials" appears after three failed attempts.

This works well for simple features. It's fast. It's easy to read. But it lacks context. It doesn't tell the story of how the user interacts with the system, which can lead to "fragmented" UX where every button works but the flow feels like a mess.

2. Gherkin Style (Scenario-Based)

If you’ve heard of Behavior Driven Development (BDD), you know Gherkin. It follows a Given/When/Then structure. This is becoming the gold standard for acceptance criteria for user stories because it translates directly into automated tests.

- Given: The user is on the "Payment" page.

- When: They enter a Visa card number that is already expired.

- Then: The "Submit" button remains greyed out and a red warning appears under the date field.

It’s verbose. It takes longer to write. But it is nearly impossible to misinterpret.

Who Actually Writes This Stuff?

There’s a common misconception that the Product Owner (PO) is the sole author of the AC. That’s a recipe for disaster. If the PO writes them in a vacuum, they might include things that are technically impossible or omit edge cases that the developers know all too well.

🔗 Read more: Is MyPillow Going Out of Business 2024: The Messy Reality Behind the Headlines

The best teams use the "Three Amigos" approach. This is a concept popularized by George Dinwiddie, and it involves a Product person, a Developer, and a Tester sitting down together. The PO explains the "what," the Dev explains the "how," and the Tester asks, "But what happens if the Wi-Fi cuts out halfway through?"

You need all three perspectives. If you're a PO and you're handing down AC like they're the Ten Commandments, stop. You're missing the collective intelligence of your team.

Real-World Example: The "Search" Feature

Let's look at a real-world scenario. Say you're building a search bar for an e-commerce site.

User Story: As a shopper, I want to search for products by name so I can find what I need quickly.

If you leave it at that, the developer might build a search that only works if the spelling is 100% perfect. Or maybe it doesn't show the price in the results. Here is how you'd actually write the acceptance criteria for user stories in this case:

- Search results must update in real-time after the 3rd character is typed.

- If no results are found, suggest "similar items" based on the last category viewed.

- Results must display the product image, title, and current price.

- The search should ignore case sensitivity (e.g., "Apple" and "apple" return the same thing).

- System must handle "fuzzy matching" for common typos (e.g., "iphnoe" should find "iPhone").

Notice how these aren't just "functional"? They're also about the experience. But they are still measurable. You can look at the screen and say, "Yes, it shows the price," or "No, it doesn't show the price."

Avoid the "Negative Space" Trap

One thing people always forget is the "negative path." We all love to describe the "happy path"—the perfect user journey where everything goes right. But software lives in the dark corners.

What happens when the database is down? What if the user tries to upload a 5GB file when the limit is 10MB? Good acceptance criteria for user stories must define the boundaries of failure. You have to tell the system how to say "no" gracefully.

Elizabeth Hendrickson, author of Explore It!, often talks about the importance of exploring the "edges." If your AC only covers the middle of the road, your software will crash the moment it hits a curve.

Common Pitfalls (The "Don'ts")

Don't be too narrow. If you specify every single hex code for a button in the AC, you’re micromanaging. That belongs in a design file (like Figma), not in a Jira ticket. Keep the AC focused on behavior.

Also, avoid "and" in a single criterion. If you find yourself writing "The system should save the user's name and send them a confirmation email and update the CRM," you've just written three criteria, not one. Split them up. If one part fails but the others work, is the story done? It’s hard to tell when you lump them together.

Lastly, stop using vague words. Words like "fast," "user-friendly," "optimal," or "efficient" are meaningless in a technical context. What is "fast"? Is it 200ms or 2 seconds? To a backend engineer, 2 seconds is an eternity. To a user on a 3G connection in a rural area, 2 seconds is a miracle. Be specific. "The page must load in under 500ms on a standard 4G connection" is a criterion. "The page should be fast" is a wish.

How to Get Started Tomorrow

You don't need a massive process overhaul to start writing better acceptance criteria for user stories. You just need a little discipline.

Start by looking at your current backlog. Pick one story. Does it have AC? If not, get your developer and your tester in a room (or a Zoom call) for 10 minutes. Ask them: "How will we prove this works?"

Write down their answers. Use those answers as your criteria.

You'll find that the first few times you do this, it feels slow. It feels like "extra work." But wait until you get to the end of the sprint. You'll notice something weird: there are fewer bugs. There’s less arguing. The demo actually goes well because everyone knew exactly what was being built.

Actionable Steps for Better Acceptance Criteria

- Audit your "Done" definition: Ensure your team agrees on what "ready for dev" looks like. If a story doesn't have at least three specific criteria, it's not ready.

- Shift Left: Bring your QA engineers into the conversation before a single line of code is written. They are the masters of edge cases.

- Use the "So That" test: For every criterion, ask "So that... what?" If you can't justify why a criterion exists, delete it.

- Focus on Outcomes, Not Inputs: Don't tell the dev how to build the engine; tell them how fast the car needs to go and what color the seats should be.

- Keep it accessible: Write in plain English. Your stakeholders should be able to read the AC and understand exactly what they are paying for.

Mastering acceptance criteria for user stories isn't about being a perfectionist. It’s about communication. It’s about making sure that the brilliant idea in your head actually makes it into the hands of the user without getting mangled along the way. Stop treating them like a chore and start treating them like the blueprint they are.