AC/DC didn't just walk into the studio to record Let There Be Rock. They went to war. It was 1977, and the music world was fracturing. On one side, you had the bloated, self-indulgent prog-rock giants playing twenty-minute synthesizer solos. On the other, the raw, snarling punk movement was threatening to make traditional rock and roll obsolete overnight. AC/DC was caught in the middle, and honestly, they didn't give a damn about either camp. They just wanted to be the loudest, tightest, most relentless band on the planet.

They succeeded.

If you listen to the album today, it still feels like a physical assault. It’s sweaty. It's abrasive. The guitars sound like they're literally melting the amplifiers, which, according to studio legend, actually happened during the recording of the title track. AC/DC Let There Be Rock represents the exact moment the band stopped being a local Australian phenomenon and became a global powerhouse of pure, unadulterated energy.

The Sound of Amps Literally Catching Fire

Most bands talk about "intensity," but AC/DC lived it at the Albert Studios in Sydney. George Young and Harry Vanda, the production duo who understood the band's DNA better than anyone, pushed them to capture a live feel that most studios try to polish away. They wanted the grit. They wanted the hiss.

During the recording of the song "Let There Be Rock," Angus Young’s Marshall amplifier actually started smoking. He was in the middle of a blistering solo, and the tubes were pushed so far past their limit that they began to disintegrate. George Young reportedly gestured through the glass for Angus to keep going. He didn't want to lose the take. That’s the sound you hear on the record—a man playing through equipment that is actively dying. It’s glorious.

The tracklist is a masterclass in pacing. You have "Go Down," inspired by the infamous "Super Ruby," which sets a sleazy, heavy tone right out of the gate. Then there's "Dog Eat Dog," a cynical look at the music business that feels more relevant now than it did forty years ago. Bon Scott’s lyrics were never just about beer and women; he had a sharp, observational wit that captured the struggle of the working class and the absurdity of the rock star life.

Bon Scott and the Art of the Story

Bon wasn't a "singer" in the traditional, operatic sense. He was a narrator. A poet of the gutters. In "Whole Lotta Rosie," he tells a true story about a one-night stand in Tasmania with a woman who, let’s just say, didn't fit the typical 1970s groupie mold. It’s hilarious, respectful, and incredibly heavy all at once.

He had this way of making you feel like you were sitting at the bar with him. When he screams "Let there be light / Sound / Drums / Guitar," it’s not a request. It's a genesis myth for the working man. He was the bridge between the old-school blues shouters and the burgeoning hard rock scene. Without his charisma on this specific album, the band might have been written off as just another loud group from the outback.

🔗 Read more: The Middle Explained: Why Brick Heck Is the Character You Can't Forget

Why the International Version Matters

If you're a vinyl collector, you know the headache. The Australian release and the international release of Let There Be Rock aren't the same. The original Aussie version included "Crabsody in Blue," a slow, tongue-in-cheek blues number about, well, exactly what the title suggests.

When Atlantic Records brought the album to the rest of the world, they swapped that track for "Problem Child" from the Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap album (which hadn't been released in the US yet). It changed the flow of the record. The international version feels more like a frantic sprint, while the Australian version has a bit more of that pub-rock breathing room. Both are essential, but the high-speed chaos of the international tracklist is what most fans identify as the "true" experience.

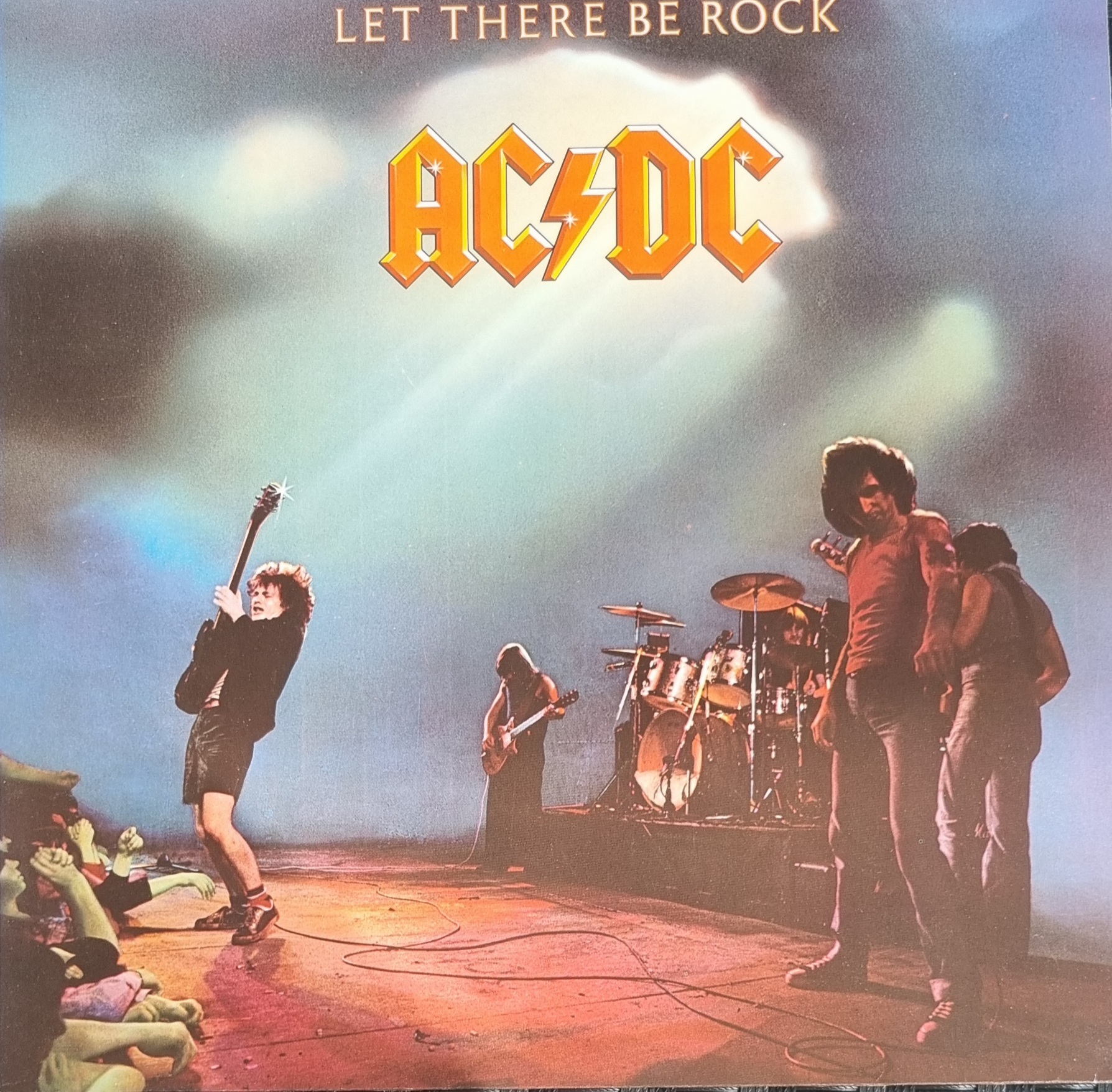

The cover art also tells a story. The international cover features the iconic AC/DC lightning bolt logo for the very first time. It was designed by Gerard Huertas, and it solidified the band's visual identity forever. Before this, the branding was a bit scattered. Now, it was iconic.

The 1977 Context: Rock vs. Punk

It's easy to forget how much people hated "dinosaur rock" in 1977. The Sex Pistols were everywhere. The Clash were reinventing the rules. AC/DC was one of the few "traditional" rock bands that the punks actually respected. Why? Because they were faster and louder than the punks were.

They didn't wear velvet capes. They didn't sing about wizards or outer space. They wore schoolboy uniforms and sweaty t-shirts. AC/DC Let There Be Rock was the band’s manifesto. It said that you didn't need a three-chord revolution if your three chords were played with enough conviction to level a building.

Angus Young’s performance on this album is otherworldly. His vibrato is wider, his phrasing is more aggressive, and his tone is pure "Gibson SG into a dimed Marshall." There are no pedals. No tricks. Just fingers and wood. If you're a guitar player, this is the textbook. You can spend years trying to replicate the "Overdose" intro, and you’ll still struggle to get that specific rhythmic pocket that Angus and his brother Malcolm created.

Malcolm Young: The Secret Weapon

We talk about Angus because he's the one doing the duckwalk and losing his shirt. But Malcolm Young is the reason this album works. His rhythm playing on "Bad Boy Boogie" is a clinic in precision. He didn't play "thick" chords; he played "big" chords. He left space for the drums and bass to breathe, which made the overall sound feel massive.

The interplay between the two brothers on this record is the gold standard for dual-guitar bands. They weren't competing. They were interlocking.

📖 Related: Who Are the 7 Dwarfs? The Real Story Behind the Names You Know

The Movie: Let There Be Rock (1980)

You can't talk about this album without mentioning the concert film. Recorded in Paris in 1979, it’s arguably the greatest document of a live rock band ever captured on celluloid. Even though it was filmed during the Highway to Hell tour, the spirit of the Let There Be Rock era is what defines it.

The footage of Angus backstage, literally needing oxygen because he's pushed himself so hard, is legendary. It shows the physical toll of this music. This wasn't a hobby for them; it was a grueling, high-stakes performance that demanded everything they had. The film captures the sweat dripping off the ceiling and the sheer volume that seems to vibrate the camera lens itself.

Modern Legacy and Misconceptions

People sometimes think AC/DC is "simple." That’s the biggest mistake you can make. It’s easy to play an A-chord and a D-chord. It’s nearly impossible to play them with the swing and "stink" that this band had in 1977.

Critics at the time often dismissed them as primitive. They missed the point. The "primitivism" was intentional. It was a stripping away of all the nonsense that had cluttered rock music in the mid-70s. When you listen to "Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be," you aren't listening to a band that doesn't know how to play complex music; you're listening to a band that has chosen to prioritize the groove above all else.

💡 You might also like: Why When Can I See You Again Lyrics Still Hit Different a Decade Later

- Production: Handled by Vanda & Young, giving it a raw, "in-the-room" feel.

- Engineering: Mark Opitz helped pioneer the "Australian Sound" here—dry drums and upfront guitars.

- Sales: It took a while to go Platinum, but its influence far outweighs its initial chart positions.

- Equipment: Angus used his 1968 Gibson SG; Malcolm used his "Beast" (a 1963 Gretsch Jet Firebird with the pickups ripped out).

Actionable Steps for the True Fan

If you want to truly appreciate AC/DC Let There Be Rock, don't just stream it on your phone speakers. This music wasn't designed for tiny plastic drivers.

- Find a high-quality vinyl press. Specifically, look for an early Albert Productions Australian pressing if you can afford it, or the 180g remasters which handle the low end surprisingly well.

- Watch the Paris '79 film. Don't just listen. See the physical exertion. Watch Malcolm's right hand—it's a metronome made of flesh and bone.

- Analyze the lyrics. Stop thinking of them as "party songs" for a second. Look at "Overdose." It’s a dark, heavy track about addiction (even if the addiction is a person). There’s a weight there that gets overlooked.

- Compare the versions. Listen to "Crabsody in Blue" back-to-back with "Problem Child." Notice how the inclusion of the blues track changes your perception of the band's range.

The reality is that rock music rarely reaches this level of purity anymore. Everything is aligned to a grid, pitch-corrected, and polished until the soul is gone. Let There Be Rock is the antidote to that. It’s messy, it’s loud, and it’s perfect because of its flaws. It’s the sound of five guys from Australia deciding that they were going to conquer the world or die trying. And for a few weeks in a Sydney studio in 1977, they were the only thing that mattered.