You’ve probably seen it. That specific, glowing shade of translucent green sitting on a dusty shelf in a thrift store or tucked away in your grandmother’s china cabinet. It’s distinct. It’s heavy. It feels like a piece of history because, honestly, it is. Anchor Hocking green glassware isn't just a collection of old cups and saucers; it's a massive, sprawling catalog of American industrial design that somehow survived the Great Depression and the transition into the modern era.

People get obsessed with this stuff. It’s easy to see why once you hold a piece of Manhattan pattern or a Soreno bowl. There is a weight to it that modern IKEA glass just can’t replicate. But if you’re trying to collect it, or even just identify that one weird pitcher you found, you’ve got to know what you’re looking at. The history is messy.

The Depression Era and the Uranium Glow

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: the "glow." A lot of the early Anchor Hocking green glassware—specifically the stuff made during the late 1920s and throughout the 1930s—actually contains uranium. Not enough to hurt you, basically, but enough to make the glass fluoresce a bright, neon green under a UV light. This is what collectors call "Vaseline glass" or "Uranium glass."

During the Depression, Anchor Hocking (which formed in 1937 after the merger of Hocking Glass Company and Anchor Cap & Closure Corporation) was a powerhouse. They were churned out by the millions. They were cheap. Sometimes they were even given away for free in boxes of oatmeal or at movie theaters.

Imagine going to see a flick and walking out with a "Block Optic" sherbet dish. That was the reality. This wasn't luxury. It was survival-mode marketing. Because the Hocking Glass Company focused on machine-pressed glass rather than hand-blown crystal, they could undercut everyone on price. This is why you find so much of it today. It was the Tupperware of its time, but made of sand and fire instead of plastic.

Identifying the Green: From Forest to Mint

Not all green is created equal in the world of Hocking. You have to be able to distinguish between the eras, or you’re going to overpay for something common.

Forest Green is perhaps the most iconic. It’s deep. It’s moody. It looks like a pine tree in the middle of July. Anchor Hocking produced this heavily in the 1950s and 60s. If you find a smooth, dark green pitcher with a weighted bottom, it’s almost certainly Forest Green. It doesn't glow under blacklight, but it catches sunlight in a way that makes a kitchen feel grounded.

Then you have Spring Green or Avocado. This is the 1970s calling. It’s a bit more muted, a bit more "earthy." If you find the "Soreno" pattern—which looks like crinkled bark or frozen water—in this shade, you’ve found a staple of Mid-Century Modern design.

📖 Related: Lakeside Country Club Los Angeles: Why This Spot Is Still the City's Quietest Power Play

And don't forget the translucent green of the Depression era. This is often found in patterns like:

- Princess: Very ornate, lots of scrolls and swags.

- Block Optic: Simple, geometric, very "Art Deco."

- Mayfair (Open Rose): Intricate floral designs that feel very feminine and delicate, despite being machine-made.

What Most People Get Wrong About Value

I see it all the time at estate sales. Someone sees a green plate and thinks they’ve hit a $500 jackpot. Slow down.

Value is dictated by condition and rarity, obviously, but also by "completeness." A single green tea cup is worth maybe $5. A set of twelve with the matching saucers, the cream and sugar set, and the serving platter? Now you’re talking real money. The "Cameo" pattern (sometimes called "Dancing Girl") is a big one here. If you find the shaker set in green, you're looking at a piece that collectors actually fight over because those small peripheral items broke easily over the last 90 years.

Condition matters more than you think. "Sick glass" is a real term. It’s that cloudy, milky film that won't wash off. It’s actually a chemical change in the glass from being put through modern dishwashers too many times. Harsh detergents and high heat literally etch the surface. If the green looks hazy, it’s basically worthless to a serious collector. Always check for "flea bites"—tiny chips along the rim that you can feel with your fingernail even if you can't see them.

The 1970s Pivot: Why "Suburban" Green Matters

By the time we hit the 1960s and 70s, Anchor Hocking was leaning hard into the "suburban dream" aesthetic. This is where the Anchor Hocking green glassware shifted from delicate pressed patterns to chunky, textured styles.

The "Soreno" and "Milano" patterns are the kings of this era. They are rugged. You could probably drop a Soreno bowl on a rug and it would bounce. These pieces are currently seeing a massive resurgence because they fit the "Grandmillennial" and "MCM" (Mid-Century Modern) decor trends. People want that textured, organic look.

Interestingly, the green used in the 70s was often called "Avocado" or "Olive," reflecting the interior design trends of the time (think shag carpets and wood paneling). While not as "fancy" as the Depression-era stuff, it’s arguably more usable for a modern dinner party. You can actually put chips and dip in a Soreno bowl without feeling like you’re handling a museum artifact.

Spotting the Fakes and Reproductions

Is there fake Anchor Hocking? Sorta.

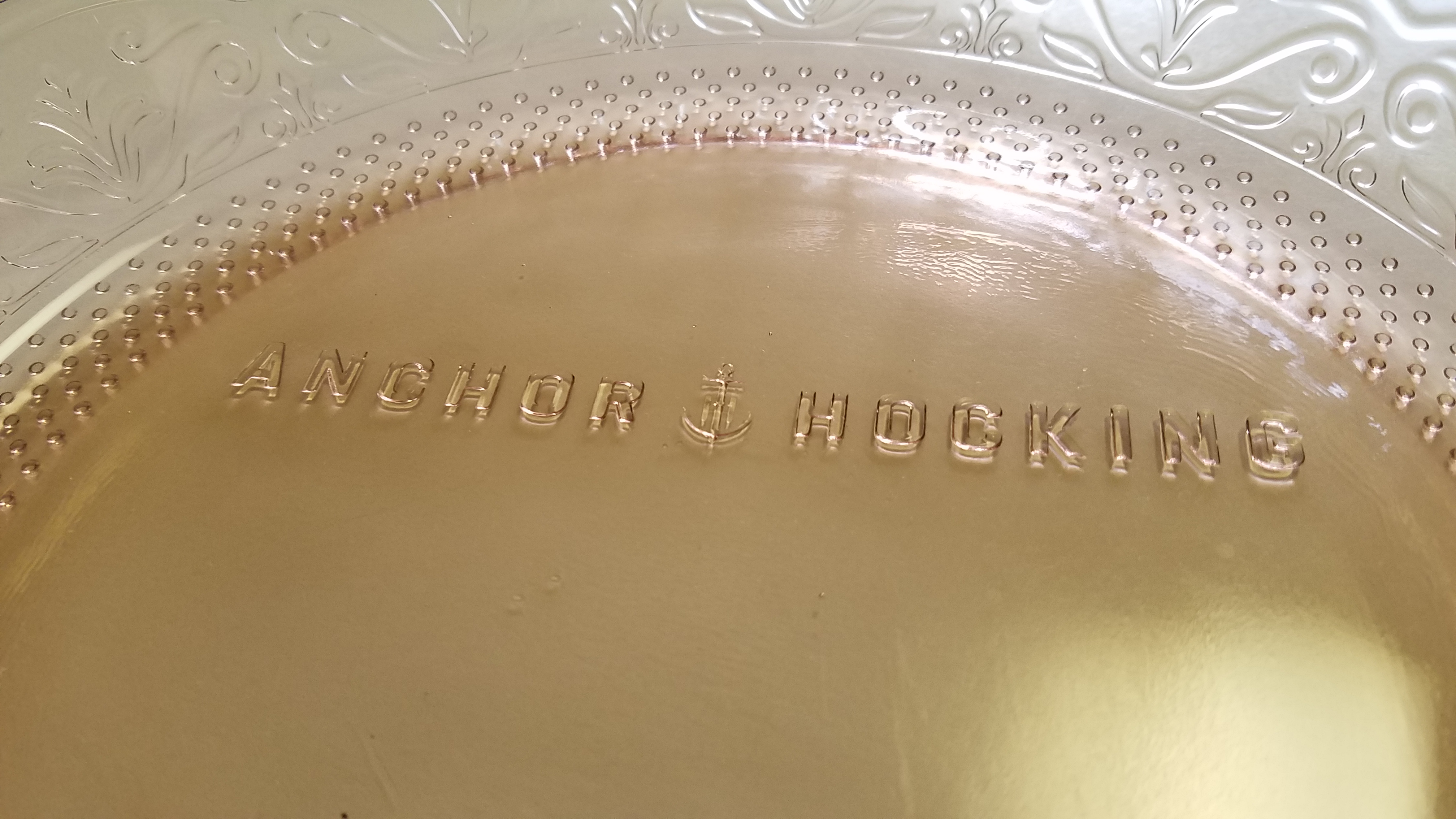

It’s less about "fakes" and more about "reissues." In the 1990s and early 2000s, some patterns were brought back. For a novice, a 1930s original and a 1990s reproduction look identical. But look at the bottoms. Original Hocking glass often has a very faint "H" over an anchor symbol, though not always. Many Depression-era pieces weren't marked at all.

The real giveaway is the "mold lines." Older glass has more prominent seams from the two-part molds used in the 30s. Also, the color. Newer green glass often looks "too perfect." It lacks the tiny bubbles (seeds) or slight striations found in glass made during a time when quality control was a guy with a squint and a lantern.

Real-World Rarity: The "Holy Grail" Pieces

If you're hunting, keep your eyes peeled for the Royal Ruby or Forest Green mixing bowl sets. But specifically, look for the "Dot" or "Bullseye" patterns.

✨ Don't miss: What is a Coptic Orthodox Christian? The Ancient Faith You Might Not Know

Most people don't realize that Hocking made experimental runs. There are shades of green that don't quite fit the "Forest" or "Spring" categories—almost a teal or a seafoam. These were often short-lived trials. If you find a piece of Anchor Hocking green glassware in a pattern you recognize but a shade you’ve never seen, buy it immediately.

Also, look for the "Fire-King" heat-resistant line. While most people associate Fire-King with Jadeite (that opaque, milky green), they did produce transparent green ovenware. A green transparent Fire-King loaf pan is a rare beast indeed. It combines the utility of Pyrex with the aesthetic of Hocking.

The Chemistry of the Green

Why green? Why was it so popular?

Economics, mostly. Iron impurities in sand naturally turn glass a yellowish-green. To get clear glass, you have to add "decolorizers" like manganese or selenium. During the war years and the Depression, those chemicals were expensive or needed for the war effort. By leaning into the green, Hocking could use cheaper raw materials and market the color as a "style choice" rather than a cost-cutting measure. It was brilliant branding.

They turned a manufacturing limitation into an iconic American look.

Taking Care of Your Collection

If you buy this stuff, treat it with respect.

- No Dishwashers. I cannot stress this enough. The heat will kill the luster and the detergent will etch the surface. Hand wash only with mild soap.

- Avoid Thermal Shock. Don't take a green glass bowl from a cold fridge and pour hot soup into it. It will crack. These aren't tempered like modern Borosilicate glass.

- Storage. If you stack plates, put a piece of felt or even a paper towel between them. The foot of one plate will scratch the face of the one below it.

How to Start Your Collection Today

Don't go to eBay first. You'll pay premium prices and shipping glass is a nightmare—half of it arrives as green glitter.

Go to the "junk" shops in small towns. Look under the tables at flea markets. The best way to learn is tactile. Feel the weight of a genuine Hocking piece. Look for the "H" logo on the bottom of 1960s-era tumblers.

Actionable Steps for New Collectors:

- Get a small UV flashlight. Take it to thrift stores. If a piece of green glass glows bright neon, it’s Uranium glass from the 1930s. It’s an instant way to verify age.

- Focus on one pattern. It’s tempting to buy every green glass piece you see. Don't. You'll end up with a cluttered mess. Pick "Manhattan" (the ribbed circles) or "Soreno" and try to build a full service for four.

- Check the edges. Run your finger (carefully!) along every rim. If it’s jagged, move on.

- Consult the "Bible". Look for books by Gene Florence. He is the gold standard for Depression glass identification. While some of his price guides are outdated due to the internet, his identification photos are unmatched.

- Join a community. Groups like the National Depression Glass Association (NDGA) have archives that show every single mold Hocking ever used.

The market for Anchor Hocking green glassware is weirdly resilient. While "brown furniture" has tanked in value, mid-century and Depression-era glass has stayed steady because it’s a "usable" collectible. It’s a way to own a piece of the 20th century that you can actually use to serve a salad or drink a gin and tonic.

Start by looking at the glassware you already have. You might be surprised to find that a "cheap" green bowl you’ve been using for keys is actually a 1934 Princess pattern piece worth more than the table it’s sitting on. Keep your eyes open for that specific glow. It’s getting harder to find, but it’s out there.