You’ve been there. It’s 8:00 PM on a Sunday, and suddenly you remember the animal cell 3d project is due tomorrow morning. You’re staring at a tub of lime gelatin and wondering if a grape can actually represent a mitochondria without dissolving into a sticky mess. It’s a rite of passage for students, honestly. But beyond the panicked crafting, these projects are actually a pretty incredible way to wrap your head around the microscopic machinery that keeps us alive.

Biology is messy.

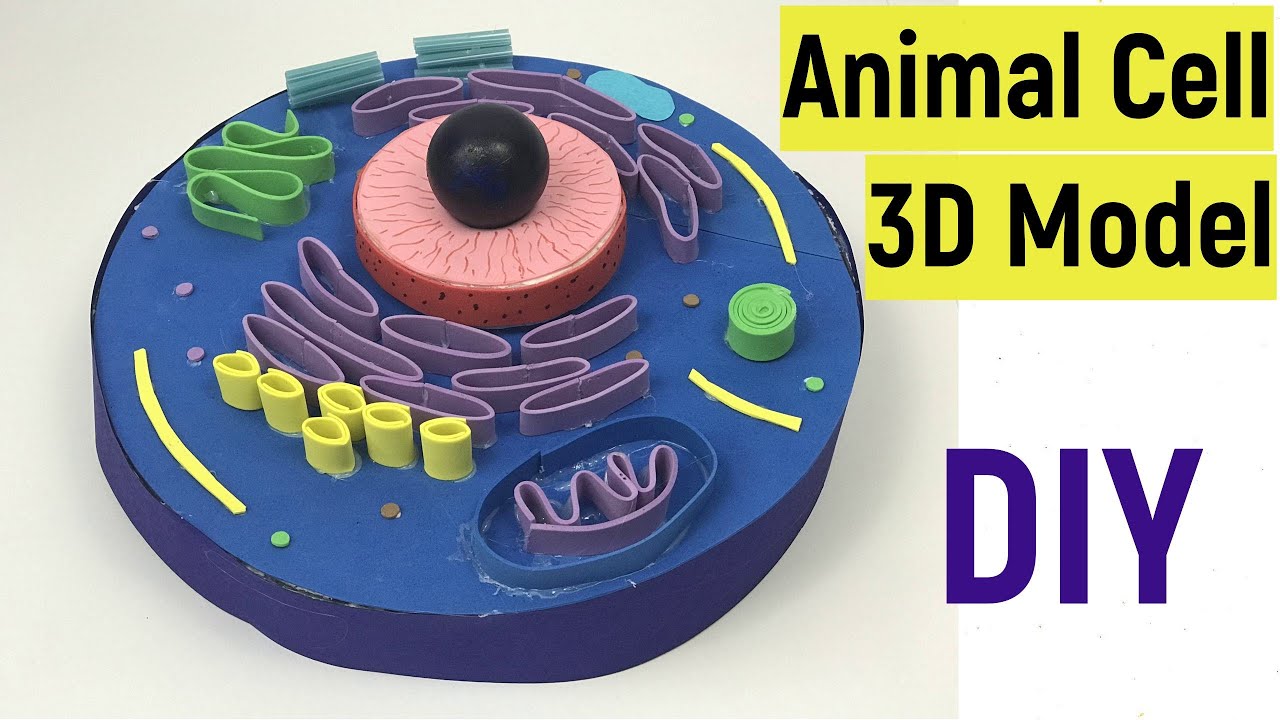

If you look at a textbook diagram, everything looks flat and color-coded, like a neat little map of a city. Real life isn't like that. An animal cell is a crowded, pulsing, three-dimensional balloon filled with salty soup and frantic protein robots. When you build a 3D model, you're trying to capture that chaos in a way that makes sense to the human eye.

Moving Beyond the Styrofoam Sphere

Most people reach for the Styrofoam ball first. It makes sense. It’s round, it’s cheap, and it’s easy to paint. But let’s be real: Styrofoam is kind of a nightmare to work with if you want things to actually stay attached. Glue eats through it. Toothpicks wiggle out. If you’re going for a "lifestyle" approach to science—meaning you want something that looks good on a shelf and doesn't crumble—you’ve got better options.

Consider the "Shadow Box" method. Instead of a floating ball, you use a deep picture frame or a wooden box. This gives you a literal stage. It allows you to use hanging elements, like fishing line, to suspend the nucleus or the Golgi apparatus. It creates a sense of depth that a flat poster just can't touch. Plus, it won't roll off the kitchen table and shatter into a million white beads.

Actually, the best models often use recycled materials. A crumpled piece of tinfoil makes a surprisingly accurate-looking mitochondria because of those inner folds, known as cristae. An old coiled-up phone cord? Perfect for the Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). It’s all about finding textures that mimic the biological function.

The Anatomy of Your Animal Cell 3D Project

You can’t just throw random junk into a bowl and call it a day. You need the "Big Seven" organelles. If you miss these, your grade is going to tank, and your understanding of cell biology stays superficial.

The Nucleus is the boss. It’s usually the largest thing in your model. If you’re building this, think of it as the hard drive. It holds the DNA. A lot of students use a golf ball or a small orange, which is fine, but if you want to be fancy, cut it in half. Show the "nucleolus" inside. That’s where ribosomes are born. It adds that layer of "I actually read the textbook" energy that teachers love.

Then there’s the Cytoplasm. This is the jelly. In a physical project, this is the hardest part to represent because it’s technically everywhere. If you’re doing a non-edible model, clear hair gel or even just the empty space in your box works. But remember, the cytoplasm isn't just "filler." It’s a structural scaffold.

The Powerhouse and the Post Office

We have to talk about the Mitochondria. It’s a meme at this point—everyone knows it’s the powerhouse of the cell. But why? It’s because of those internal membranes where ATP (energy) is produced. If your animal cell 3d project just uses a kidney bean for this, you’re missing a chance to show the "folds." Use a piece of ribbon candy or folded felt instead.

The Golgi Apparatus is basically the FedEx of the cell. It takes proteins, packages them into little bubbles called vesicles, and ships them out. It looks like a stack of pancakes. Seriously. Use layers of folded cardboard or even pieces of fruit leather if you’re going the edible route.

Edible Models: The Sticky Reality

Let’s talk about the cake. Or the pizza. Or the giant bowl of Jello. Edible cell models are the most popular version of the animal cell 3d project for a reason: you get to eat your homework.

But there’s a trap here.

Jello is notoriously unstable. If you put heavy candy (like a jawbreaker for a nucleus) into warm gelatin, it will sink to the bottom faster than a stone. You have to let the gelatin partially set, then "suspend" your organelles in layers. It takes hours. Honestly, it’s a lesson in patience.

If you want a model that survives the bus ride to school, go with a cake. Frosting is like biological glue. You can use fruit roll-ups for the ER, sprinkles for ribosomes, and a sliced plum for the nucleus. It’s sturdy, it’s recognizable, and it doesn't melt in the sun.

📖 Related: Why Chair Covers for Wedding Planning Are Actually the Hardest Choice You'll Make

Common Mistakes That Ruin the Vibe

- Scale issues: Don’t make your ribosomes the size of your nucleus. Ribosomes are tiny dots. They should be the smallest thing on your model—like grains of sand or tiny glitter.

- Missing the Centrioles: These look like little bundles of pasta (macaroni works great). They are crucial for cell division. Most people forget them because they aren't as "famous" as the mitochondria.

- The Cell Membrane: Don't just leave the edge of your project bare. An animal cell has a flexible lipid bilayer. If you’re using a box, line the inside with plastic wrap to show that it’s a contained, fluid environment.

Why This Project Actually Matters in 2026

We live in an era where biotechnology is moving at light speed. We're literally 3D printing human tissues now. Understanding the spatial relationship of organelles isn't just some dusty academic exercise. It’s the foundation of modern medicine. When scientists talk about mRNA vaccines or CRISPR gene editing, they are talking about manipulating the very parts you’re gluing onto your Styrofoam ball.

When you hold a 3D model, you realize how crowded a cell is. It's not a big empty room. It's a packed factory floor. That realization is the "aha!" moment that sticks with you long after you’ve thrown the project in the trash.

Actionable Steps for a Winning Project

If you’re starting right now, here is the move. Forget the "perfect" store-bought kit.

First, pick your base based on your transport method. If you have to walk to school, do a shadow box or a cake. If your parents are driving you, you can risk the Jello or the elaborate Styrofoam sculpture.

📖 Related: Why That Pic of a Gecko You Just Saw is Probably Lying to You

Second, create a key. This is the secret to an A+. Don’t just label the cell with toothpicks. Create a separate, professionally written legend that explains what each material represents and, more importantly, what that organelle actually does.

Third, focus on the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Most people mess this up. Make sure you have both "Rough" (with ribosomes/dots) and "Smooth" (no dots) versions. The Rough ER is usually hugged right up against the nucleus. Putting it on the far edge of the cell is a classic rookie mistake.

Finally, don't overcomplicate the "animal" part. Animal cells are generally irregular or roundish. Unlike plant cells, they don't have a rigid cell wall or chloroplasts. Keep it squishy. Keep it organic. And honestly? Use a little hot glue. It solves 90% of the structural integrity issues you’ll face at midnight.

Get the nucleus centered, get your "pancake" Golgi stacked, and make sure those mitochondria have their folds. You’ve got this.