You probably remember the basic sketches from seventh-grade biology. One was a roundish blob, and the other was a rigid green rectangle. It felt simple back then. But honestly, when you look at the actual mechanics of how life sustains itself, the decision to compare the animal cell and plant cell becomes a lot more than a memorization game. It’s a study in survival strategies. One builds a fortress to stand tall against the wind; the other builds a flexible, moving machine to go find dinner.

Cells are the smallest units of life, but they aren’t "simple." They are busy cities. If you zoom into your own bicep, you’ll find trillions of animal cells working in tandem. If you look at the leaf of a fiddle-leaf fig, you’ll see plant cells doing something humans can only dream of: literally eating sunlight.

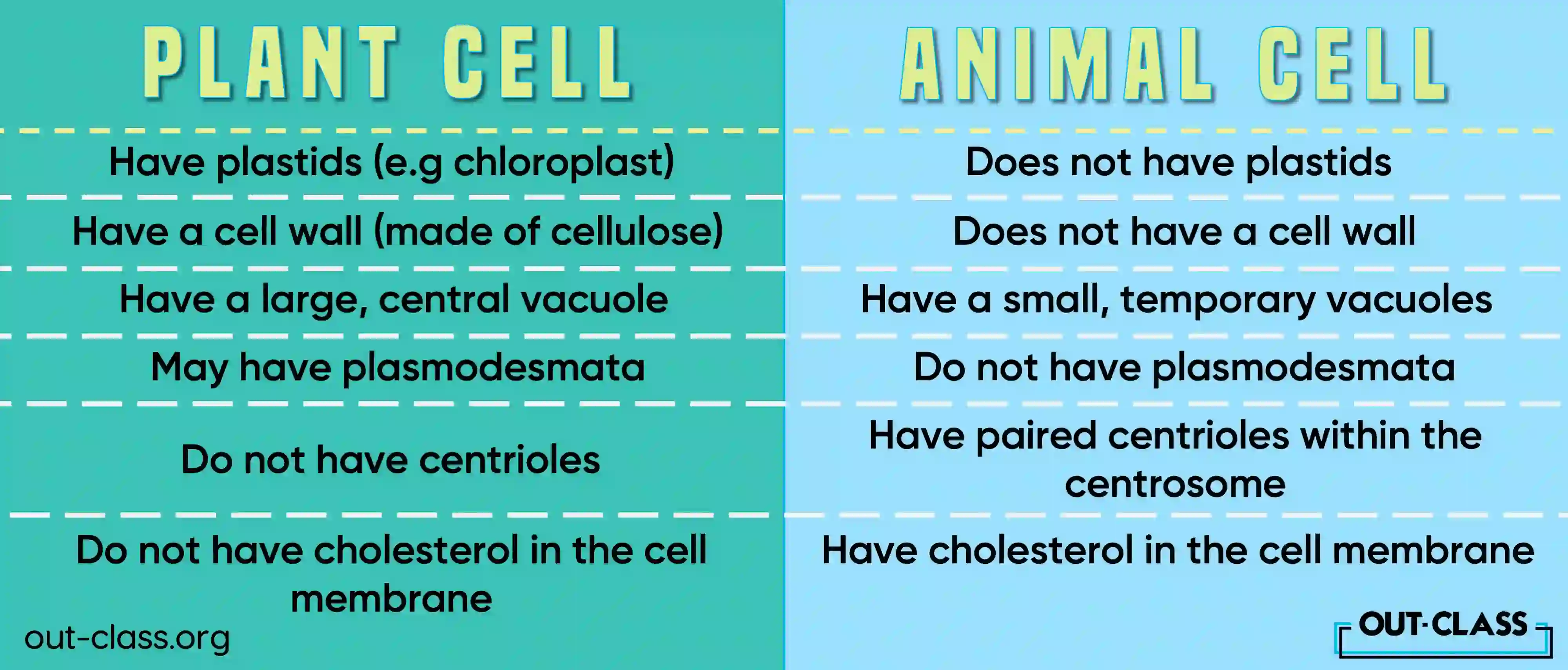

The Wall vs. The Membrane

The biggest, most obvious difference is the housing. Plant cells are encased in a cell wall made of cellulose. It’s tough. It’s the reason why celery stalks crunch when you bite them and why giant redwoods can grow hundreds of feet into the air without a skeleton. Without that wall, a tree would just be a puddle of green goo on the forest floor.

Animal cells? We don’t have that. We have a flexible cell membrane. This is why you can move your arm, blink your eyes, and squeeze through a tight space. We trade structural rigidity for mobility. If our cells had walls, we'd be as stiff as a board. Think of it like this: plants live in a brick house, while animals live in a high-tech, elastic tent.

What’s inside the wall?

Inside that wall, the plant cell still has a plasma membrane, just like we do. It’s a double-layered gatekeeper. In plants, this membrane is usually pushed tight against the wall because of something called turgor pressure. This pressure is basically the cell inflating itself with water. When a plant wilts, it’s not because the cells died—it’s because that pressure dropped. The "tent" inside the "brick house" deflated.

Energy: Solar Panels vs. Power Plants

If we want to compare the animal cell and plant cell effectively, we have to talk about how they get their "batteries" charged.

Animals are consumers. We eat. We take in glucose, and our mitochondria—the famous "powerhouse of the cell"—break that sugar down into ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate). Mitochondria are fascinating because they actually have their own DNA. Scientists like Lynn Margulis championed the endosymbiotic theory, suggesting these organelles were once independent bacteria that got swallowed by a larger cell and just... stayed.

Plants have mitochondria too. That’s a common misconception; people think plants only have chloroplasts. Nope. They need mitochondria to process energy just like us. But plants have the ultimate "cheat code": chloroplasts.

These are the green organelles that perform photosynthesis. They contain chlorophyll, which absorbs light energy to synthesize food. While we’re out here working 9-to-5s to buy groceries, a plant is just sitting in the sun, making its own lunch from carbon dioxide and water.

The Vacuole Situation

Size matters here. Both cells have vacuoles, which are basically storage sacs. But in a plant cell, the Central Vacuole is a monster. It can take up 90% of the cell's volume. It stores water, waste, and nutrients. In an animal cell, vacuoles are tiny, numerous, and often temporary. We use them for transport or getting rid of waste, but we don't rely on them to keep our physical shape.

The Weird Stuff: Centrioles and Lysosomes

Usually, people say lysosomes are only in animal cells. That’s a bit of a "textbook lie" for simplicity. While they are rare in plants (vacuoles do most of the heavy lifting there), animal cells are packed with lysosomes. These are the "suicide bags" or recycling centers. They contain digestive enzymes that break down cellular debris. If a cell is damaged beyond repair, the lysosomes can actually burst and digest the cell from the inside out to protect the rest of the organism. It’s metal.

👉 See also: 710 W 168th St New York NY 10032: The Nerve Center of Columbia’s Medical Campus

Then you have centrioles.

These are barrel-shaped structures that help with cell division in animals. When it’s time for one cell to become two, centrioles organize the "spindle fibers" that pull DNA apart. Most higher plants don't have centrioles; they manage to divide just fine using a different microtubule-organizing center. It’s a subtle difference, but it matters to biologists studying mitosis.

Shape and Symmetry

Go look at a microscope slide of human cheek cells. They look like fried eggs dropped on a floor—irregular, squishy, and unique. Now look at an onion skin. It looks like a brick wall. This regularity in plant cells allows them to stack and form the rigid tissues needed for stems and roots.

Animal cells are highly specialized. A neuron (nerve cell) looks like a long, spindly tree with branches, while a red blood cell looks like a tiny donut without a hole. Because we don't have a cell wall, our cells can take on wild shapes to perform specific jobs, like contracting muscles or carrying oxygen.

How They Divide (The Cytokinesis Gap)

When it comes time to multiply, the two types of cells have a bit of a "divorce" disagreement.

- Animal cells pinch. A ring of proteins tightens around the middle of the cell like a drawstring bag until it snaps into two. This is called a cleavage furrow.

- Plant cells build. Because of that rigid wall, they can't just "pinch." Instead, they build a brand-new wall right down the middle. This is called a cell plate. It starts as a few bubbles in the center and expands outward until the two daughter cells are walled off from each other.

Why Should You Care?

Understanding the nuances when you compare the animal cell and plant cell is actually the foundation of modern medicine and agriculture.

For instance, many antibiotics work by attacking cell walls. Since human (animal) cells don't have walls, the medicine can kill the bacteria (which do have walls) without hurting you. If we had cell walls, penicillin would be a poison, not a cure.

Similarly, herbicides often target chloroplasts or the specific way plants store energy. By knowing exactly how a plant cell differs from an animal cell, scientists can create chemicals that kill weeds but leave the neighborhood dogs and squirrels perfectly fine.

Real-World Nuance: The Exceptions

Biology loves to break its own rules. There are "animal-like" protists that have some plant features and "plant-like" algae that can move. There are even sea slugs (Elysia chlorotica) that "steal" chloroplasts from the algae they eat and can then live off sunlight for months. Life is messy, and the lines between these categories are sometimes thinner than we think.

Summary of the Key Differences

To keep it straight, honestly, just think about what the organism does.

- Plants stay still and grow tall: They need walls, big water tanks (vacuoles), and solar panels (chloroplasts).

- Animals move and eat: They need flexibility (no walls), specialized shapes, and lots of "digestion" centers (lysosomes).

Actionable Insights for Biology Students and Enthusiasts

If you are studying these for an exam or just trying to wrap your head around the microscopic world, don't just memorize a list. Try these specific steps to truly master the concept:

1. Sketch the "Why," not just the "What"

Draw an animal cell and a plant cell. Instead of just labeling "Cell Wall," write "This keeps the tree from falling over." Instead of "Chloroplast," write "This is the solar panel." Connecting the structure to the function makes it impossible to forget.

2. Use the "Balloon in a Box" Mental Model

To understand turgor pressure in plants, imagine a balloon (the cell membrane and vacuole) inside a cardboard box (the cell wall). When the balloon is full of air, it pushes against the box and the whole thing is rigid. When the air lets out, the box stays, but the structure becomes weak. That is exactly why your lettuce goes limp in the fridge.

3. Observe it in your kitchen

Take a piece of wilted celery and put it in a glass of water. Wait a few hours. When the celery becomes crisp again, you are witnessing the plant's central vacuoles filling up and the turgor pressure returning. You are seeing cell biology in action.

4. Compare DNA and Organelles

Remember that both cells share a nucleus, cytoplasm, ribosomes, and the Golgi apparatus. These are the universal "machinery" of complex life (Eukaryotes). Focus your energy on the differences—the Wall, the Chloroplast, and the Vacuole size—as these are the "upgrades" that define the kingdom.