You’re staring at a lab report. It’s a wall of numbers—sodium, chloride, potassium—and then you see it: anion gap. It’s usually a small number, maybe an 8 or a 12. Honestly, most people ignore it until a doctor starts looking worried or mentions the word "acidosis."

It sounds like a gap in your teeth or maybe something from a physics textbook. But in reality, it's one of the most elegant ways your body signals that something is chemically "off" deep inside your blood. It isn't a direct measurement of a single substance. Instead, it's a mathematical calculation that tells us if your blood is becoming too acidic.

What is a Anion Gap and Why Do We Measure It?

Think of your blood as a finely tuned electrical circuit. For you to stay alive, your blood must remain electrically neutral. This means the number of positively charged particles (cations) must equal the number of negatively charged particles (anions).

Your lab test usually measures the heavy hitters. On the positive side, we look at sodium. On the negative side, we look at chloride and bicarbonate. But here’s the kicker: if you add up the measured negative ions, they don't quite equal the positive ones. There is a "gap."

That gap isn't actually empty space. It’s filled with "unmeasured" anions like phosphates, sulfates, and proteins like albumin. When that gap gets too wide, it usually means your body is producing an "unmeasured" acid—like lactic acid or ketones—that is eating up your bicarbonate.

The standard formula used in hospitals is:

$$\text{Anion Gap} = \text{Sodium} - (\text{Chloride} + \text{Bicarbonate})$$

If your sodium is 140, your chloride is 105, and your bicarbonate is 25, your gap is 10. That's totally normal. But if that number jumps to 20? That’s when medical teams start moving fast.

💡 You might also like: What Can I Do to Suppress My Appetite? Real Talk on Why You’re Always Hungry

The Normal Range is Moving

One thing that trips people up is what qualifies as "normal." If you look at older medical textbooks from the 1970s or 80s, they’ll tell you a normal anion gap is 8 to 16 mEq/L.

But modern labs use different technology now.

Most hospitals today use ion-selective electrodes. This tech is so much more accurate that it actually shifted the goalposts. Nowadays, a "normal" range is often considered 3 to 10 mEq/L or 4 to 12 mEq/L, depending on the specific machine the lab uses. If you see a 13 on your report, don't panic immediately—always check the reference range listed right next to your result. It varies by zip code and equipment.

Why Albumin Matters More Than You Think

There is a massive blind spot in the standard anion gap calculation: Albumin. Albumin is a protein, and it carries a negative charge. It makes up a huge chunk of those "unmeasured anions."

If you are very sick or malnourished, your albumin levels drop. When albumin drops, your "normal" anion gap should also drop. A patient with a very low albumin might have an anion gap of 10, which looks healthy on paper, but for them, it’s actually dangerously high. Doctors often have to "correct" the gap for albumin to get the real story. For every 1 g/dL drop in albumin, the "normal" anion gap drops by about 2.5.

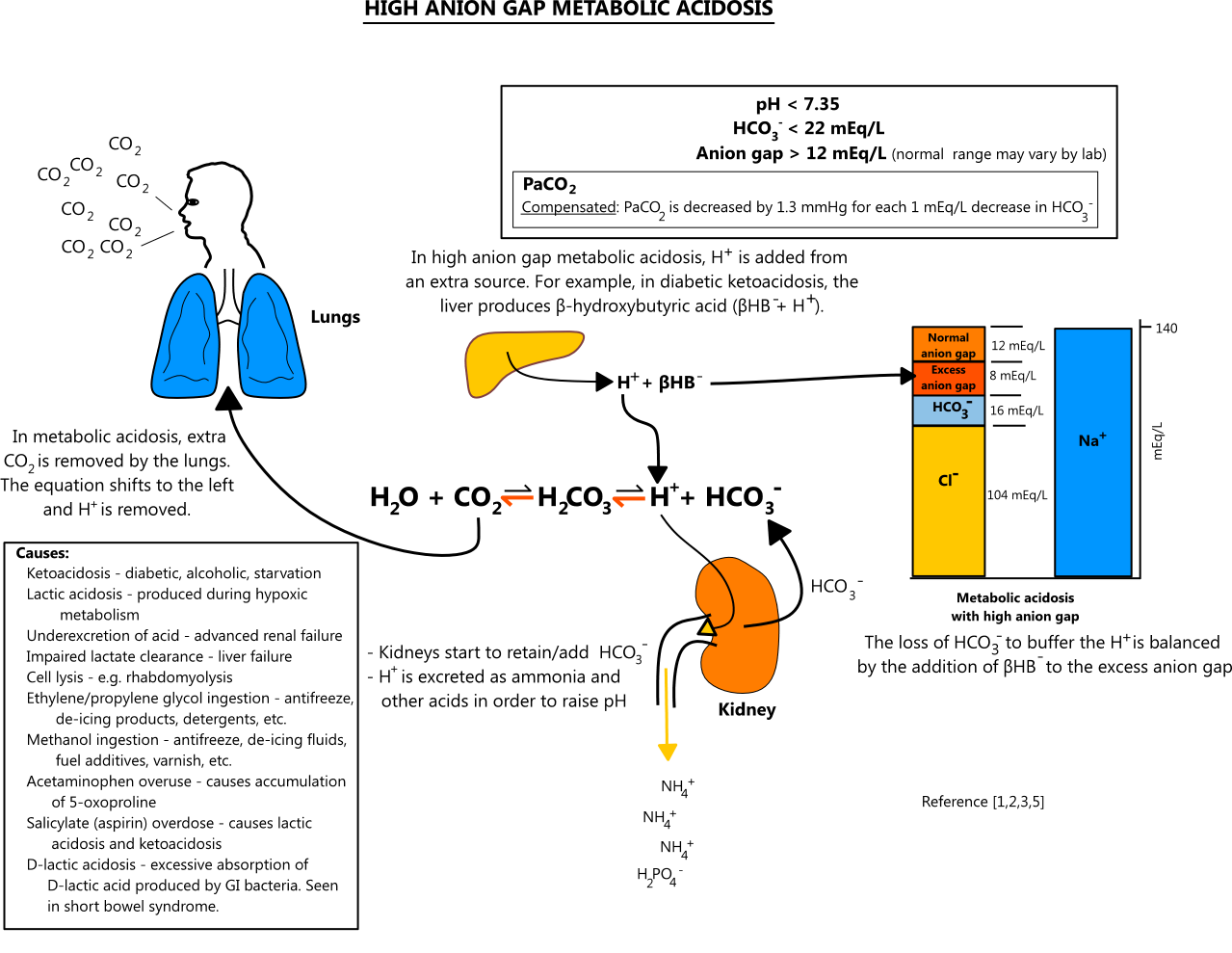

When the Gap Gets Wide: High Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis

This is the big one. Doctors call it HAGMA. It sounds like a monster from a low-budget horror flick, but it's just shorthand for "your blood is too acidic and we found the gap."

When the gap is high, it means your body is dealing with an "acid load" it can't handle. Medical students use the famous MUDPILES acronym to remember what causes this. It’s a bit grim, but it’s how the pros think:

- Methanol (Wood alcohol poisoning)

- Uremia (Kidney failure)

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

- Paraldehyde or Propylene glycol

- Iron or Isoniazid

- Lactic Acidosis (Often from sepsis or extreme exercise)

- Ethylene Glycol (Antifreeze)

- Salicylates (Aspirin overdose)

Lactic acidosis is probably the most common reason for a high gap in a hospital setting. If your tissues aren't getting enough oxygen—maybe because of a severe infection or heart issues—they start producing lactic acid. This acid dumps hydrogen ions into the blood, which then bind to bicarbonate to neutralize the threat. As bicarbonate disappears, the math changes, and the anion gap widens.

The "Low" Anion Gap Mystery

It's actually pretty rare to have a low anion gap. Most of the time, it's just a lab error. But when it's real, it’s usually fascinating from a diagnostic perspective.

🔗 Read more: Measles Outbreak in Florida: Why This Virus is Making a Comeback and What You Can Actually Do About It

One common cause is hypoalbuminemia (low protein), which we talked about earlier. But a low gap can also be a "smoke alarm" for something more serious like Multiple Myeloma. In this type of blood cancer, the body produces abnormal proteins (paraproteins) that are positively charged. These extra positive charges mess with the electrical balance, causing the calculated gap to shrink or even become a negative number.

If you see a gap of 2 or 1, and your protein levels are normal, a doctor might want to look closer at your bone marrow or blood proteins.

What You Should Actually Do With This Information

If you've just received lab results and see an "abnormal" anion gap, the first thing is to breathe. A single number in isolation is almost never a diagnosis.

Doctors look at the "triad": the anion gap, the pH of your blood, and your physical symptoms. If you feel fine and your gap is slightly out of range, it might be dehydration or a simple lab fluke. However, if you're feeling short of breath, confused, or extremely fatigued, that number becomes much more significant.

Real-World Steps to Take:

- Check the Albumin: Look at your protein or albumin levels on the same lab report. If albumin is low, your anion gap is likely "underestimated."

- Look at the Bicarbonate (CO2): If your anion gap is high AND your bicarbonate is low (usually below 22 mEq/L), that’s a much stronger sign of metabolic acidosis.

- Hydrate and Re-test: If you were fasted or dehydrated during the blood draw, your electrolytes can shift. Often, a repeat test after a few glasses of water shows a perfectly normal gap.

- Review Medications: Certain drugs, especially metformin (for diabetes) or topiramate (for migraines), can subtly influence your body's acid-base balance.

- Ask the "Why": If a doctor tells you your gap is high, ask: "Is this a production problem (like lactic acid) or a clearance problem (like my kidneys)?"

The anion gap is essentially a detective’s tool. It doesn't tell us exactly what is wrong, but it points the finger in the right direction. It tells the medical team whether they need to look for toxins, check kidney function, or manage blood sugar more aggressively.

Understanding this "invisible" math helps you advocate for yourself. It turns a scary-looking lab value into a manageable piece of data.

Most labs are just a snapshot in time. Your body is constantly buffering, adjusting, and breathing out CO2 to keep that gap exactly where it needs to be. If you're generally healthy, your "gap" is likely doing exactly what it's supposed to: staying quiet in the background while your internal chemistry keeps the lights on.

Actionable Insight: If you are reviewing your own labs, do not look at the anion gap in a vacuum. Compare it specifically to your BUN and Creatinine (kidney markers). If those are high alongside a high anion gap, the issue is likely renal clearance. If they are normal, the cause is more likely metabolic, such as intense physical exertion or an underlying inflammatory process. Always request a "Corrected Anion Gap" if your Albumin is below 3.0 g/dL to ensure your doctor isn't missing a hidden acidosis.