Let's be real for a second. Most students look at a page of AP Calculus BC problems and see a collection of hieroglyphics designed to ruin their GPA. It's intimidating. You’ve got Taylor series that stretch into infinity, polar coordinates that make circles feel like a personal attack, and those infamous integration by parts scenarios that seem to go on forever. But here’s the thing—the "BC" in the course doesn't stand for "Basically Crazy," even if it feels that way at 2:00 AM while you're staring at a divergent p-series.

Actually, it's just more math. That's the secret.

The College Board structures this exam to test how you handle depth, not just how fast you can memorize a formula. If you can master the logic behind the messiest AP Calculus BC problems, you aren’t just passing a test. You’re learning how the physical world actually functions. From the way your phone’s GPS calculates your location using triangulation to the fluid dynamics of a rocket launch, this is the language of the universe. It’s messy, sure. But it’s also incredibly logical once you stop fighting the symbols and start seeing the patterns.

The Polar Area Trap Most People Fall Into

Polar coordinates are where things usually start to go sideways for people. In AB Calculus, everything is nice and rectangular. You have an $x$ and a $y$. Life is good. Then BC introduces $r$ and $\theta$. Suddenly, you’re trying to find the area of a cardioid or a leaf on a rose curve.

🔗 Read more: How a Watch Defending Your Life Became a Reality for Modern Survival

The biggest mistake? Forgetting the $1/2$.

The formula for polar area is $\frac{1}{2} \int_{\alpha}^{\beta} [r(\theta)]^2 d\theta$. People lose points every single year because they treat it like a standard integral. They forget that we aren’t dealing with rectangles anymore; we are dealing with sectors of a circle. Imagine a tiny slice of pie. The area of that slice is based on the angle and the radius squared. If you forget that squared term or that constant out front, the whole problem falls apart.

But the real trick isn't just the formula. It's the bounds. Determining where the curve starts and ends—$\alpha$ and $\beta$—is the hardest part of these AP Calculus BC problems. You have to set $r = 0$ or find where two curves intersect. If you can’t visualize the "sweep" of the angle, you’re guessing. And guessing doesn't work when you're looking for the area inside one loop of $r = 3 \sin(2\theta)$.

Why Taylor Series Are Actually Just Fancy Polynomials

If you ask any BC student what keeps them up at night, they’ll say "Sequences and Series." Specifically, Taylor and Maclaurin series.

Honestly, they look terrifying. The summation notation alone is enough to make anyone want to close the textbook and go for a walk. But think about it this way: a Taylor series is just a way to turn a complicated, "difficult" function like $e^x$ or $\sin(x)$ into a simple polynomial. Polynomials are easy. We love polynomials. We can derive them and integrate them in our sleep.

The AP exam loves to ask you to find the "Lagrange Error Bound." This sounds like a high-level physics concept, but it's basically just asking: "How much did we mess up by stopping our polynomial early?"

- The Center: Everything happens around $x = c$.

- The Ratio Test: This is your best friend. Use it to find the interval of convergence. If the limit is less than 1, you're golden.

- Term-by-term: You can differentiate or integrate a series just like a regular function. It’s almost like cheating.

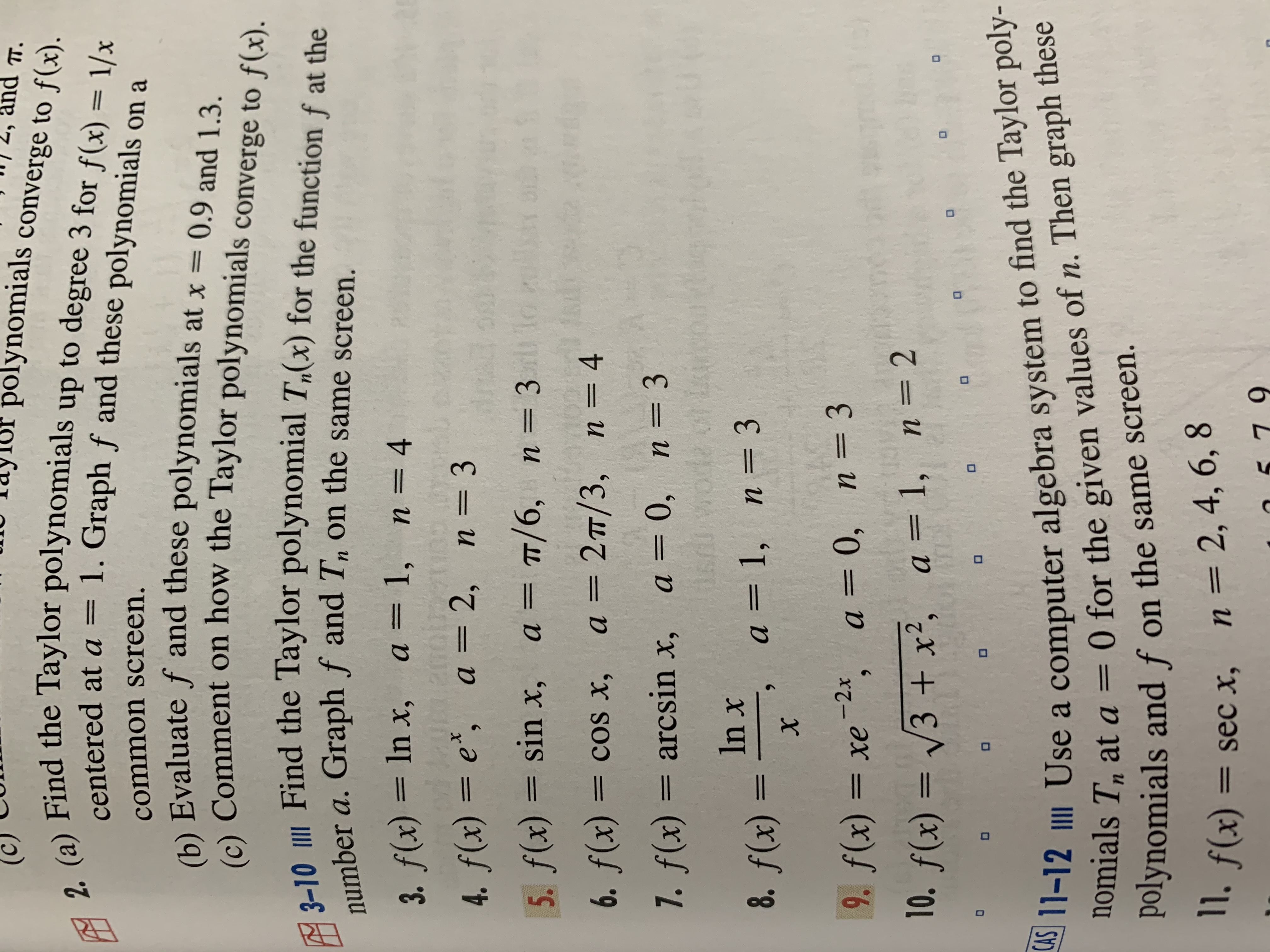

A classic problem might give you a function $f(x)$ and ask for the third-degree Taylor polynomial centered at $a=1$. You just take the derivatives, plug in the center, and follow the pattern: $f(a) + f'(a)(x-a) + \frac{f''(a)}{2!}(x-a)^2$. It’s a recipe. Follow the steps, and the monster becomes a kitten.

The Integration Techniques That Separate AB from BC

In AB, you have $u$-substitution. In BC, you have a whole toolbox of surgical instruments. Integration by Parts (IBP) and Partial Fractions are the heavy hitters.

📖 Related: Spatial Mode iPhone 16 Explained (Simply)

You’ve probably heard of the acronym LIATE (Logs, Inverse Trig, Algebraic, Trig, Exponential). It’s a solid rule of thumb for choosing your $u$ in IBP, but don't rely on it blindly. Sometimes the AP graders throw a curveball where the "standard" choice leads to an infinite loop.

Then there’s Partial Fraction Decomposition. This is basically "un-adding" fractions. If you have a denominator like $(x-2)(x+3)$, you split it up into $A/(x-2) + B/(x+3)$. It’s more algebra than calculus, really. But under the pressure of a timed exam, the algebra is usually where the wheels come off.

Parametric and Vector-Valued Functions

This is where the math starts to feel like physics. You aren't just looking at a curve on a graph; you’re looking at the path of a particle over time $t$.

In these AP Calculus BC problems, you're often asked for the "total distance traveled" or the "speed" of a particle.

Speed isn't just the derivative. It's the magnitude of the velocity vector: $\sqrt{(dx/dt)^2 + (dy/dt)^2}$.

- Velocity: The first derivative of the position vector.

- Acceleration: The second derivative.

- Position: The integral of velocity (don't forget the initial condition $+C$!).

The nuance here is often in the wording. If the problem asks for "displacement," you just integrate the velocity. If it asks for "total distance," you have to integrate the speed. That distinction is the difference between a 4 and a 5 on the exam.

Dealing with Improper Integrals

Sometimes an integral goes to infinity. Or maybe the function itself hits a vertical asymptote and shoots off to infinity. These are improper integrals, and they require a very specific ritual to solve on the AP exam.

You can't just plug in $\infty$. The College Board will dock points for that. You have to use limits. Instead of $\int_1^{\infty}$, you write $\lim_{b \to \infty} \int_1^b$. It seems like a pedantic detail, but it’s about mathematical rigor. If the limit exists, the integral "converges." If it doesn't, it "diverges."

It’s binary. No in-between.

Real Strategies for the Free Response Questions (FRQs)

The FRQs are where the battle is won or lost. You get six problems. Two with a calculator, four without.

On the calculator portion, let the machine do the heavy lifting. Don't try to integrate something complex by hand if you have a TI-84 or Nspire in front of you. Write down the setup (the "integral expression") and then just write the answer. The graders want to see the setup and the final result with units. They don't care about your intermediate arithmetic.

On the non-calculator side, keep your work organized. If you’re doing a multi-step Taylor series problem, label your derivatives. If you're doing a differential equation with separation of variables, show the step where you actually separate the $y$'s and $x$'s. That specific step is often worth the first point of the problem.

Common Misconceptions That Hurt Your Score

A big one is the "P-series" vs. "Geometric series" confusion.

A p-series is $\sum 1/n^p$. It converges if $p > 1$.

A geometric series is $\sum ar^n$. It converges if $|r| < 1$.

It sounds simple, but when you're stressed, it’s easy to flip the rules.

Another one? The Difference between "Absolute" and "Conditional" convergence.

Just because a series like $\sum (-1)^n / n$ (the alternating harmonic series) converges doesn't mean it converges "absolutely." If you take the absolute value, it becomes the harmonic series, which diverges.

Actionable Steps to Master BC Calculus

Stop trying to do every problem in the book. It’s a waste of time. Instead, focus on these specific habits:

- Download Past FRQs: Go to the College Board website. Download the last five years of scoring guidelines. Don't just look at the problems; look at how they award points. Sometimes you get 3 points just for setting up an integral correctly, even if you get the math wrong.

- The "No-Calculator" Drill: Practice your basic trig values and log rules. You’d be surprised how many people fail a complex calculus problem because they forgot what $\ln(1)$ or $\sin(\pi/6)$ is.

- Master the Error Bounds: Spend a dedicated hour on Alternating Series Error Bound and Lagrange Error Bound. Most students skip this because it's hard, which means it’s an easy place to gain an edge over the curve.

- Graph Everything: When you see a polar or parametric problem, do a quick sketch. It doesn't have to be art. It just has to help you see the boundaries of the motion.

- Analyze Your Mistakes: When you get a problem wrong, don't just look at the right answer. Figure out if it was a "Calculus" error (wrong formula) or an "Algebra" error (wrong simplification). If it's algebra, you need more practice reps. If it's calculus, you need to go back to the concepts.

Success in AP Calculus BC isn't about being a genius. It's about being a detective. You look at the clues—the given function, the interval, the rate of change—and you pick the right tool from your belt to solve the case. Whether it's a Taylor polynomial or a complex volume by shells, the logic remains the same. Focus on the "why" and the "how" will eventually take care of itself.