Honestly, if you look at a map of the Indian Ocean today, it’s easy to see it as a series of disconnected vacation spots—Dubai’s skyscrapers, Kerala’s backwaters, or the white sands of Zanzibar. But for over a thousand years, this massive blue expanse was essentially an "Arab Lake." Not in a political sense, but in a way that defined how the world ate, dressed, and even prayed.

When people talk about global trade, they usually default to the Silk Road. You know, camels, dunes, and Marco Polo. But the real action—the heavy lifting of the ancient and medieval world—happened on the water. And for a long, long time, Arabs were the undisputed masters of these waves.

The Monsoon Whisperers

The ocean is scary. Even now, with GPS and satellite weather tracking, it’s unpredictable. But back in the 8th or 9th century, Arab sailors were basically "hacking" the climate. They realized that the Indian Ocean wasn't just a random body of water; it was a giant machine powered by the Monsoon winds.

💡 You might also like: Southwest Airlines Naked Passenger: What Really Happened on That Flight to Chicago

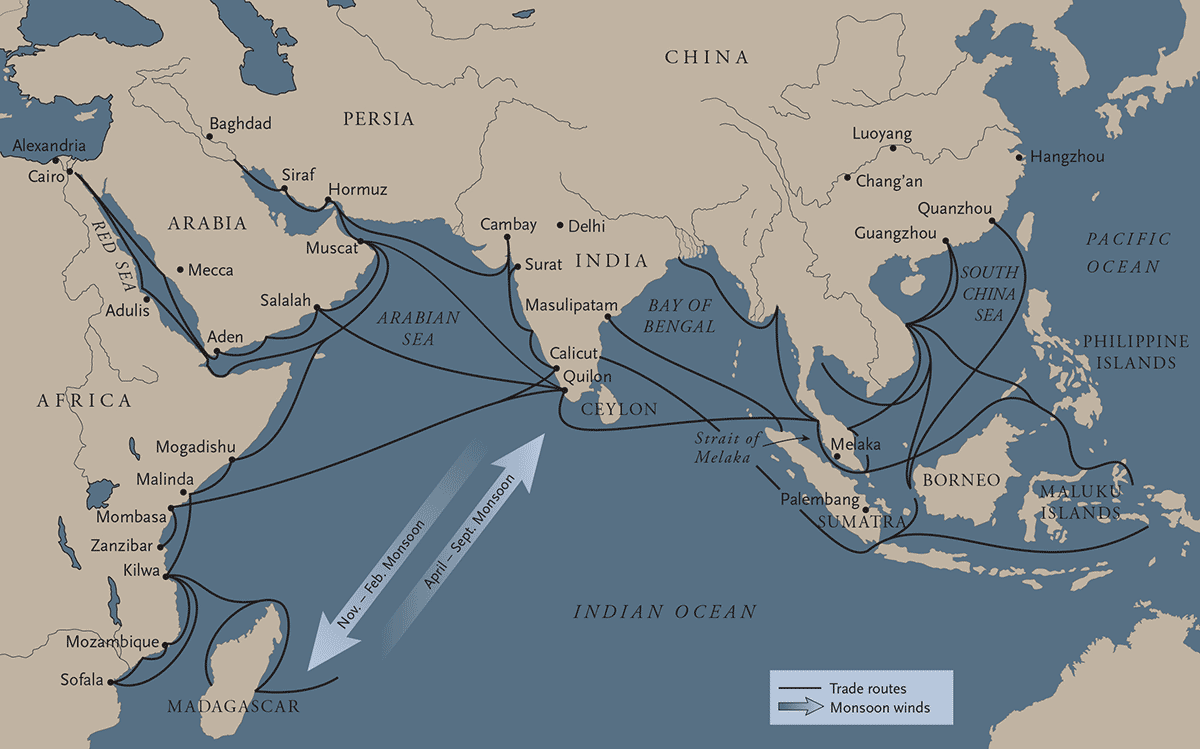

Between May and September, the wind blows hard toward India. From November to April, it flips and blows back toward Arabia and Africa. Arab navigators, like the legendary Ahmad ibn Majid (who some claim helped Vasco da Gama, though that's a spicy historical debate), didn't just survive these winds—they timed their entire lives around them.

Because they had to wait for the winds to change, these sailors didn't just drop off cargo and leave. They stayed. For months. They married into local families in places like the Malabar Coast of India or the Swahili coast of Africa. This created a "maritime silk road" that was less about a single path and more about a massive, pulsing network of people who actually knew each other.

Why the Dhow Changed Everything

You’ve probably seen a Dhow. It’s that wooden ship with the triangular "lateen" sail. It looks a bit fragile compared to a modern cargo ship, doesn't it?

But here is the thing: the dhow was a masterpiece of engineering for its time. Unlike European ships that used iron nails (which would rust and snap in the tropical salt water), Arab dhows were often "sewn" together with coconut fiber.

👉 See also: Why the Grand Floridian Hotel gingerbread house is basically the MVP of Disney Christmas

This made the hulls flexible. When the ship hit a coral reef or took on a massive wave, the wood could flex and absorb the impact instead of shattering. It’s kinda like the difference between a glass bottle and a plastic one. This tech allowed them to reach places others couldn't, carrying everything from African ivory and gold to Indian teak and Chinese porcelain.

The Cargo: It wasn't just Pepper

Sure, everyone wanted pepper. It was the "black gold" of the Middle Ages. But the trade was way more diverse than a spice rack.

- Horses: This is a big one people miss. South Indian kingdoms were constantly at war and they obsessed over Arabian horses. Arab merchants made a killing shipping stallions from the Gulf to ports like Kozhikode (Calicut).

- Frankincense and Myrrh: Coming straight from the Dhofar region of Oman and Yemen. This stuff was essential for religious rituals from Rome to China.

- Timber: Arabia is, well, not exactly known for its lush forests. They needed Indian teak to build the very ships they used for trade.

- Dates and Pearls: The staples of the Gulf.

The Religion of the Merchant

One of the most fascinating things about the Arabs role in Indian Ocean trade is that it wasn't spread by the sword. Unlike the later European arrivals—the Portuguese, Dutch, and British—who showed up with cannons and a "convert or else" attitude, the Arabs brought Islam through the ledger book.

Basically, being a Muslim merchant was a massive networking advantage. If you were a trader in Indonesia and you converted to Islam, you suddenly had a "common code" with traders in Cairo, Baghdad, and Kilwa. There was a shared system of contract law, a common language (Arabic), and a level of trust that bypassed tribal borders.

It’s why you see these incredible "creole" cultures today. The Swahili language is literally a mix of Bantu and Arabic. The food in Kerala has Middle Eastern DNA. It wasn't a conquest; it was a slow, centuries-long conversation.

📖 Related: African Countries Beginning with T: What Most People Get Wrong

What Happened When the "Lords of the Sea" Arrived?

Everything was going great until about 1498. That's when the Portuguese, led by Vasco da Gama, rounded the Cape of Good Hope.

The Europeans didn't want to join the trade; they wanted to own it. They were shocked to find that the "heathen" lands they were "discovering" were already part of a sophisticated, wealthy, and mostly peaceful Arab-Indian-Chinese trade network.

The Portuguese introduced something the Indian Ocean hadn't seen much of: naval warfare for monopoly. They started sinking dhows and demanding "cartazes" (passports) for any ship to move. This was the beginning of the end for the Arab dominance of the high seas, but the cultural footprint they left? That’s still there.

Real-World Takeaways: Why You Should Care

If you're looking to understand the "Blue Economy" or why certain coastal regions are the way they are, you have to look at this history. It’s not just dusty dates in a textbook.

- Look at the Architecture: Next time you're in Stone Town, Zanzibar, or a port city in Gujarat, look at the doors. Those heavy, carved wooden doors? That’s a direct link to the Arab-Indian trade axis.

- The Food Connection: The use of saffron, dried fruits, and specific meat-grilling techniques in coastal India didn't happen by accident. It's the "taste" of the trade routes.

- The Language of Trade: Even the word "check" (as in a bank check) comes from the Arabic saqq. This trade network literally invented many of the financial tools we use today.

If you want to experience this history yourself, skip the big resorts. Go to the dhow-building yards in Sur, Oman, or walk through the old port areas of Kochi, India. You can still smell the history there—a mix of sea salt, old wood, and dried spices that has been wafting across the ocean for over a millennium.

To really get a feel for this era, check out the Travels of Ibn Battuta. He was the ultimate "Indian Ocean influencer" before the term existed, and his accounts of the 14th-century maritime world are way more entertaining than any history book. If you're planning a trip to the region, start by mapping out the old Swahili or Malabar ports; that’s where the real soul of the Indian Ocean lives.