You’ve probably seen the headlines. They pop up every few months, usually alongside a grainy photo of a barn or a biologist in a white hazmat suit. It’s easy to tune it out. We’ve had "bird flu" in the background of our lives for decades. But honestly, the situation with avian bird flu Canada is facing right now is different than it was five years ago. It’s weirder. It’s more persistent. And for the first time, it’s hitting closer to home for humans in ways that have scientists actually leaning in and paying attention.

The H5N1 strain isn't just a "bird" problem anymore.

Since the current highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) wave kicked off around 2022, we’ve seen millions of birds culled across the prairies, Ontario, and BC. But the real shift? The virus is jumping. It’s in the milk in the US. It’s in the skunks in your backyard. And recently, we’ve seen the first domestic human cases in North America that weren’t just "mild eye infections." If you're wondering if you should still be feeding the ducks or if your eggs are safe, you aren't alone.

The Reality of Avian Bird Flu Canada: It’s Not Just a Seasonal Blip

For a long time, we thought of bird flu like a bad storm. It blows in with the migratory birds in the spring, causes some chaos in poultry farms, and then blows out. That's not the case anymore. The virus has become endemic in wild bird populations. This means it's basically here year-round.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has been working overtime. Since 2022, more than 11 million domestic birds in Canada have been impacted. Think about that number. That’s a staggering blow to farmers in places like the Fraser Valley, which is basically the "ground zero" for these outbreaks due to the sheer density of farms and its location on a major migratory flyway. When a single farm gets hit, the response is brutal: the entire flock is usually culled to prevent the virus from mutating or spreading. It's devastating for the agricultural economy, but it's the only tool we currently have.

Why the Jump to Mammals Changes the Math

This is where things get a bit spooky. In 2024 and heading into 2025, we started seeing a massive uptick in mammal infections. We’re talking seals on the East Coast, foxes in Ontario, and even domestic cats. When a virus jumps from a bird to a mammal, it has to figure out how to live in a body with a different temperature and different cellular receptors. Every time it makes that jump, it’s like the virus is taking a "coding class" on how to infect humans better.

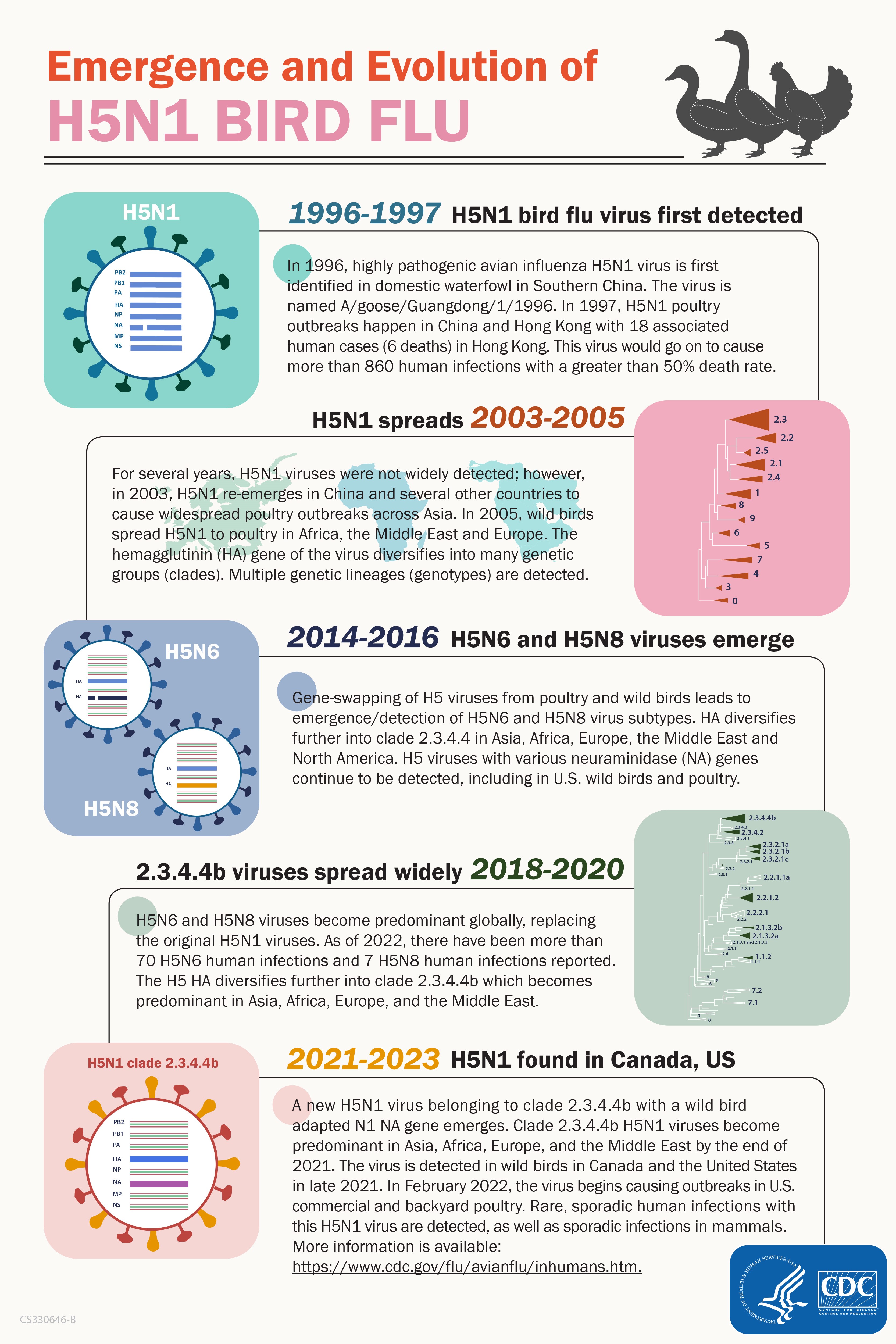

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) are watching the "clade 2.3.4.4b" very closely. This specific version of H5N1 has shown a terrifying ability to spread among species. The biggest red flag recently wasn't even in Canada—it was the discovery of the virus in dairy cattle in the United States. Since our borders aren't exactly "bird-proof" or "cow-proof," Canadian officials had to pivot quickly.

Is the milk safe? Yes. Basically, pasteurization kills the virus. You’re fine. But the fact that it reached the udders of cows suggests the virus is evolving in ways we didn't predict. It’s no longer just about respiratory droplets; it’s about systemic infection in mammals.

What Happened with the Human Case in BC?

In late 2024, Canada recorded its first domestically acquired human case of H5 avian influenza in a teenager in British Columbia. This was a massive deal. Unlike previous cases in the US where farmworkers got "pink eye" after working with infected cows, this individual ended up in critical condition.

Public health officials, including Dr. Bonnie Henry, were incredibly transparent but also cautious. They couldn't find a direct link to a farm. This suggests the teen might have caught it from a wild animal or an environmental source.

This is the "nuance" that often gets lost in the news:

- Most human cases are "dead-end" infections (it doesn't spread person-to-person).

- The virus still lacks the specific mutations needed to easily attach to human lungs.

- However, the severity of the BC case reminded everyone that "low risk" does not mean "no risk."

If the virus ever learns to "handshake" with human cells effectively, we aren't just looking at a poultry problem. We're looking at a pandemic. Luckily, we aren't there yet. But the surveillance of avian bird flu Canada is the only thing standing between us and a nasty surprise.

The Economic Gut Punch: Why Your Grocery Bill Cares

You’ve noticed the price of eggs. It’s not just "inflation" as a generic concept. When millions of laying hens are wiped out in a single province, the supply chain breaks. Canada uses a supply management system, which usually keeps prices stable, but even that can't fully absorb the shock of a massive H5N1 outbreak.

It’s not just eggs. Turkey prices around the holidays have become a gamble. Farmers are now living in a state of constant "biosecurity lockdown." You can't just wander into a commercial barn anymore. You’re stepping through disinfectant footbaths and changing clothes. It’s intense. It’s also expensive. Those costs eventually trickle down to the person buying a carton of large Grade A eggs at Loblaws.

Misconceptions You Should Probably Stop Believing

There is a lot of junk information out there. Let’s clear some of it up.

"I should stop eating chicken." No. Just no. There is zero evidence that you can catch avian flu from eating properly cooked poultry or eggs. The virus is heat-sensitive. If you cook your chicken to an internal temperature of $74^{\circ}C$ ($165^{\circ}F$), the virus is toast. Literally.

💡 You might also like: Watching a Video of Inserting Tampon: Why Visual Learning is Changing Period Care

"The virus is only on farms."

Actually, the biggest "reservoir" is wild birds. Geese, ducks, and even hawks. If you see a dead bird on a trail, do not touch it. Don't let your dog sniff it. This is how the virus moves into residential areas.

"A vaccine for humans is ready to go."

Kinda. We have "candidate" vaccines. Governments have stockpiles of H5N1 vaccine components. But because the virus is constantly changing, a "perfect" vaccine can’t be mass-produced until we see the exact strain that starts spreading in humans. We’re prepared, but we’re not "immune."

How to Protect Yourself (And Your Pets)

It feels like one of those things you can't control, but you actually can.

First, if you have a bird feeder, keep it clean. Better yet, if there’s a local outbreak reported, take it down for a few weeks. Feeders congregate different species of birds in one spot—it’s basically a nightclub for viruses. If a sick bird poops on the feeder, every other bird that visits is at risk.

Second, keep your cats inside. Seriously. We’ve seen cases of domestic cats dying from H5N1 after catching a sick songbird or mouse. It’s a grisly way for a pet to go, and it brings the virus right onto your sofa.

Third, report dead wildlife. Don't be a hero and try to bury it yourself. Call the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative or your provincial environment ministry. They need those samples to track how the virus is moving across the country.

Actionable Steps for the Average Canadian

Living with the reality of avian bird flu Canada doesn't mean living in fear. It just means being a bit more "bio-aware."

- Check the Map: The CFIA maintains a primary control zone map. If you live in an area with active outbreaks, be extra vigilant with your pets.

- Handle Bird Feeders with Gloves: If you insist on keeping them up, wash them weekly with a 10% bleach solution.

- Cook Your Food: This is basic food safety, but it bears repeating. No "runny" wild game. Ensure everything is cooked through.

- Hunters, Be Careful: If you’re hunting waterfowl, wear gloves when dressing the bird and avoid consuming the heart or liver of birds that seem "off."

- Monitor for Symptoms: If you’ve been in contact with birds and develop a fever, cough, or—interestingly—severe conjunctivitis (red eyes), tell your doctor immediately about the bird exposure.

The situation with avian bird flu Canada is a reminder that human health and animal health are inextricably linked. We call this "One Health." We can't fix one without looking at the other. For now, the risk to the general public remains low, but the virus is definitely "testing the fences." Stay informed, keep your distance from wildlife, and keep your eggs on the frying pan until they’re done.