It’s 3:00 AM. You’re staring at the ceiling because your lower back feels like it’s being gripped by a rusty vice. You’ve tried the heating pad. You’ve swallowed the ibuprofen. Now, you’re scrolling, looking for that one "magic" move to make the ache stop. We’ve all been there. Honestly, most advice about back pain stretching exercises is either outdated or just plain dangerous if you’re in the middle of a flare-up.

People think "stretching" means pulling as hard as you can until something releases. That's a mistake. If your back is screaming, your muscles are likely in a protective spasm. Yanking on them is like trying to untie a knot by pulling both ends of the string. You just make it tighter.

Why Your Hamstrings Are Probably Lying To You

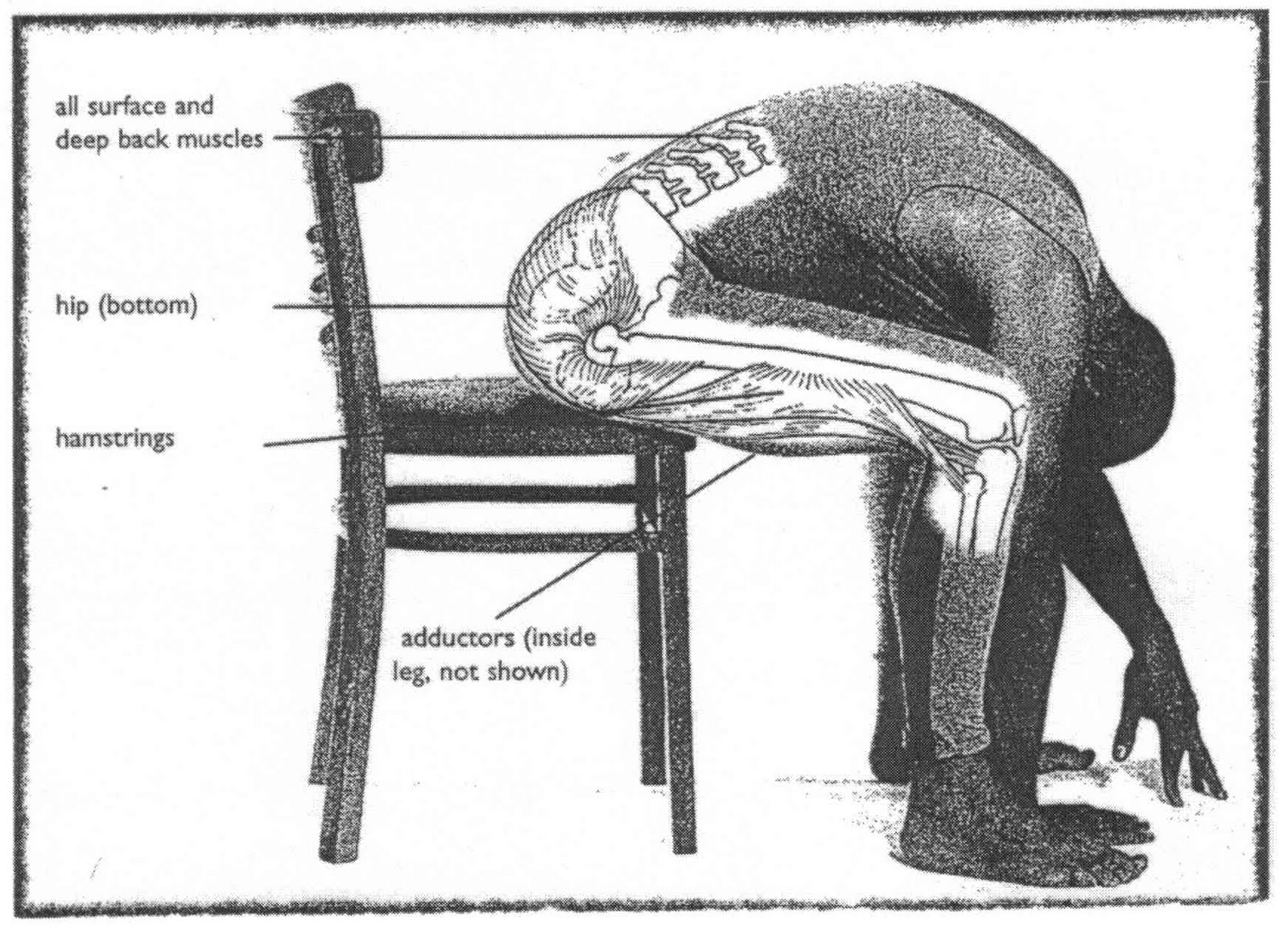

Most people with a cranky lumbar spine immediately go for the toes. They hang over their legs, reaching, straining, hoping to feel that sweet pull in the back of the thighs. Here’s the deal: tight hamstrings are often a symptom, not the cause. When your pelvis is tilted—thanks to sitting at a desk for eight hours—your hamstrings are already stretched thin like a rubber band. Stretching them further doesn't fix the back; it just irritates the sciatic nerve.

You need to look at the hip flexors. These are the muscles (specifically the psoas) that connect your spine to your legs. When they get short and tight from sitting, they literally tug your spine forward. It's a mechanical tug-of-war your back is losing.

💡 You might also like: The TB Outbreak in Kansas 2025: What Health Officials Aren't Saying (and What They Are)

The Moves That Actually Work (And How to Not Mess Them Up)

Let’s talk about the Cat-Cow. It’s the bread and butter of spinal mobility, but most people do it way too fast. They flop their belly down and crank their neck up like they’re trying to see the wall behind them. Stop that.

The goal isn't range of motion; it's segmentation. You want to feel every single vertebra moving individually. Start at your tailbone. Tuck it under. Let the curve travel up your spine until your chin finally drops. Then reverse it, starting from the tailbone again. It should feel like a slow-motion wave. If it hurts, you're pushing too far.

Child’s Pose is another one that gets bungled. If you have a disc herniation, rounding your back this much can actually push the disc material further against the nerve. If you feel a sharp "zing" down your leg, get out of that position immediately. Instead, try a de-weighted spinal decompression. Find a sturdy table or a kitchen counter. Lean onto your forearms and let your lower body hang heavy. This creates "traction," which is basically just fancy talk for giving your discs some breathing room.

The "Big Three" and Why Stuart McGill Matters

If you’ve spent any time researching back health, you’ve probably heard of Dr. Stuart McGill. He’s basically the Godfather of spinal biomechanics at the University of Waterloo. He famously dislikes "stretching" for back pain, preferring "stability."

His "Big Three" exercises aren't really stretches in the traditional sense, but they do more for long-term relief than any yoga pose.

- The Modified Curl-Up: You lie on your back, one knee bent, hands under the natural arch of your spine. You just barely lift your head and shoulders off the floor. It’s not a crunch. It’s a core stiffening maneuver.

- The Side Bridge: Propped up on your elbow, knees or feet stacked. It targets the quadratus lumborum (QL), a muscle that, when weak, causes massive side-to-side instability and back pain.

- The Bird-Dog: On all fours, reaching the opposite arm and leg out. This is the gold standard for teaching your back how to stay still while your limbs move.

Stop Stretching Your Lower Back into Oblivion

There is a weird obsession with "cracking" or "popping" the back through deep twists. You know the one—lying on your back, throwing one leg over the other until you hear a click. It feels good for about five minutes. Why? Because it triggers a release of endorphins. But you’re often just jamming the facet joints together.

If you have a "hypermobile" spine—meaning you’re naturally flexible—stretching might actually be the worst thing you can do. You don't need more flexibility; you need more "stiffness" (the good kind). Your muscles are tight because they are trying to do the job your weak ligaments can't. If you stretch those muscles away, you're removing the only thing holding your spine in place.

📖 Related: My Wife Has No Libido: Why It Happens and How Couples Actually Fix It

The Real Culprit: Thoracic Immobility

Sometimes the best back pain stretching exercises don't involve the lower back at all. They involve the upper back (the thoracic spine). If your upper back is stiff as a board—which it is, because you’re looking at a phone right now—your lower back has to move extra to compensate.

Try the Open Book stretch. Lie on your side, knees tucked up toward your chest. Reach both arms out in front of you. Take the top arm and trace a big arc over your body, trying to touch the floor behind you. Keep your knees glued together. If they lift, you’re cheating. You’ll probably feel a massive stretch through your chest and mid-back. That’s the "stuck" area that’s forcing your lower back to overwork.

Specific Scenarios: When to Walk Away

Not all back pain is created equal. If you have "centralization"—where the pain stays in your back—stretching is usually okay. But if you have "peripheralization"—pain, numbness, or tingling traveling down to your calf or toes—be extremely careful.

The McKenzie Method (specifically the prone press-up) is often used for disc issues. You lie on your stomach and gently push your chest up while keeping your hips on the floor. The goal is to "push" the pain out of the leg and back into the center of the spine. If the pain moves up your leg toward your back, you're doing it right. If it moves down toward your foot, stop. Seriously. Stop.

👉 See also: Finding What Bread Is Low in Carbohydrates (and Actually Tastes Good)

Forget the "No Pain, No Gain" Nonsense

Physical therapists generally agree on one thing: "Edge" is okay, "Ouch" is not. You want to find the edge of the tension where you can still breathe deeply. If you're holding your breath or gritting your teeth, your nervous system is in "fight or flight" mode. It will never let those muscles relax if it thinks it's being attacked by a stretch.

Think about your fascia. Fascia is the connective tissue that wraps around every muscle. It's like a wetsuit. If the wetsuit is too tight in the shoulders, it pulls on the hips. This is why stretching your calves and hip flexors often does more for back pain than touching your toes ever will.

Real World Action Plan

If you're hurting right now, don't go for a 60-minute yoga flow. You'll probably regret it tomorrow. Instead, try a "micro-dosing" approach to movement.

- Morning: Five minutes of very slow Cat-Cow. No ego. Just movement.

- Noon: Use the "Bruegger’s Relief Position." Sit on the edge of your chair, spread your knees, turn your palms out, and pull your shoulder blades back. Hold for 30 seconds. It resets your posture.

- Evening: The "90/90" position. Lie on the floor with your legs up on a couch or chair at a 90-degree angle. This flattens the spine and lets the psoas relax completely. Do this for 10 minutes.

The Nuance of Chronic vs. Acute Pain

Acute pain (you just tweaked it) needs rest and very gentle, non-weight-bearing movement. Chronic pain (it’s been hurting for three months) usually needs more aggressive strengthening and "desensitization." In chronic cases, the brain starts to perceive even normal movement as a threat. Stretching here is less about length and more about showing your brain that it’s safe to move again.

Don't ignore the psychological side, either. Stress makes you "guard" your core. You clinch your abs and jaw without knowing it. That constant tension is exhausting for the tiny stabilizer muscles in your spine. Sometimes the best "stretch" is just taking five deep diaphragmatic breaths that expand your ribcage.

Moving Forward

Consistency beats intensity every single time. Doing a two-minute hip flexor stretch every day is infinitely better than doing a grueling 90-minute mobility session once every two weeks.

If your pain is accompanied by a fever, sudden weight loss, or—and this is the big one—any changes in your bowel or bladder control, stop reading this and go to the ER. Those are "red flags" for things like Cauda Equina Syndrome. It's rare, but it's a medical emergency.

For everyone else, the path to a better back isn't about becoming a contortionist. It's about smart, targeted movement that respects the anatomy of the spine. Stop pulling on your back and start supporting it.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Assess your pain pattern: Does it feel better when you bend forward or backward? Use this to choose your moves (Press-ups for backward, Child’s Pose for forward).

- Focus on the "Hinges": Spend more time stretching your hips and ankles than your actual lower back.

- Audit your setup: If you’re stretching for 10 minutes but sitting in a slumped chair for 10 hours, you’re fighting a losing battle.

- Try the 90/90 rest: Tonight, instead of scrolling on the couch, lie on the floor with your legs up on the cushions for 10 minutes to reset your pelvic tilt.