Medical history is rarely as neat as a textbook makes it out to be. Most of us grew up hearing the name Ben Carson in the context of a "miracle" surgery. We saw the posters in school hallways or heard the stories in church. The narrative was simple: a brilliant neurosurgeon from Detroit did the impossible and separated twins joined at the head.

But if you look at the actual clinical outcomes, the story of Ben Carson and conjoined twins is a lot heavier than the "Gifted Hands" version. It’s a mix of genuine technical breakthroughs and some pretty heartbreaking long-term realities for the families involved.

The 1987 Breakthrough: Patrick and Benjamin Binder

Honestly, before September 1987, the medical community mostly viewed separating occipital craniopagus twins—those joined at the back of the head—as a suicide mission. Usually, at least one baby died on the table. Sometimes both.

Then came the Binders.

Patrick and Benjamin were seven-month-old boys from West Germany. Their parents, Theresia and Josef, were desperate. Without surgery, the boys would never sit up, crawl, or even turn over. They’d spend their lives staring in opposite directions, flat on their backs.

The "Suspended Animation" Strategy

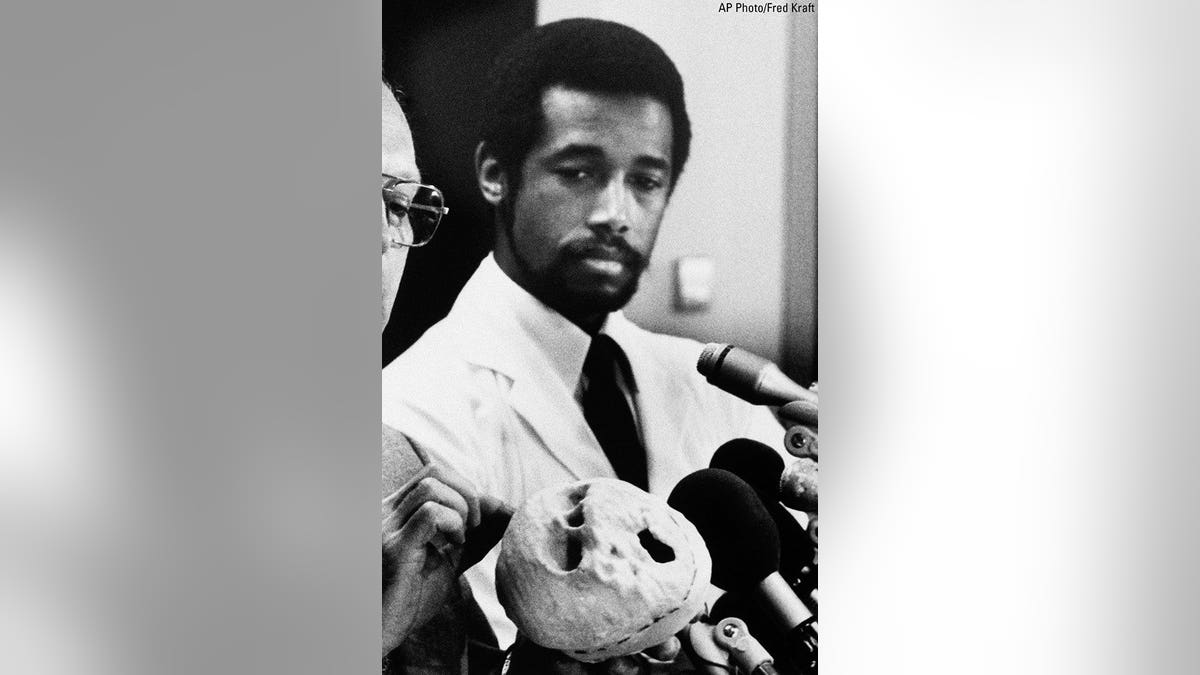

Carson didn't just walk in and start cutting. He led a massive 70-person team at Johns Hopkins. They spent five months rehearsing with dolls held together by Velcro.

The biggest hurdle was the superior sagittal sinus. That's a massive vein that drains blood from the brain. The Binder twins shared it. If you cut it, they’d bleed out in seconds. To solve this, Carson and his team used a radical technique: hypothermic arrest.

- They dropped the twins' body temperature to 68°F (20°C).

- Their hearts were stopped.

- Blood flow ceased entirely.

Basically, they put the boys in a state of suspended animation. This gave the surgeons a 60-minute window to separate the vein and reconstruct it without the babies bleeding to death.

🔗 Read more: What is a middle age crisis and why it feels so different for everyone

It worked. Sorta.

The Part Nobody Talks About: The Aftermath

In a technical sense, the surgery was a triumph. The tables were pulled apart, and for the first time in history, both twins survived the separation of that specific brain connection.

But the "happily ever after" didn't really happen.

The boys returned to Germany, and the news cycle moved on. Years later, we found out the truth was grim. Patrick and Benjamin were left profoundly disabled. Patrick suffered a setback in the hospital when he choked on food, depriving his brain of oxygen. He never spoke and eventually passed away.

Benjamin fared slightly better but remained developmentally like an infant. He couldn't feed himself or speak. In 1993, Theresia Binder told a German magazine that she felt "guilty forever" for consenting to the surgery because of the lack of quality of life for her sons.

It Wasn't Just One Surgery

Most people think Carson did this once and then became a politician. Actually, he was involved in several other high-profile separation attempts. The results were all over the place, which just goes to show how risky neurosurgery is at this level.

✨ Don't miss: Signs of Kidney Stones: Why That Random Back Pain Might Be Something Else

- The Makwaeba Twins (1994): These girls from South Africa were joined at the head. Sadly, they both died during the surgery due to complications. It was a massive blow to the team.

- The Banda Twins (1997): This is the "big win." Joseph and Luka Banda from Zambia were joined at the top of the head (type 2 vertical craniopagus). Carson led a 28-hour surgery. This time, both boys survived and, crucially, both were neurologically normal. They grew up, went to school, and lived independent lives.

- The Bijani Sisters (2003): This was the most controversial. Ladan and Laleh Bijani were 29-year-old Iranian women. They were adults with law degrees who desperately wanted to be separated. Doctors had turned them down for decades because the risk was too high. Carson joined an international team in Singapore to try. Tragically, both sisters died on the operating table from blood loss.

The Legacy of the "Gifted Hands" Era

So, was it a success? It depends on who you ask.

If you ask a medical historian, they’ll say Ben Carson’s work with conjoined twins changed the game. He proved that hypothermic arrest could be used for complex neurosurgery. He refined the use of scalp expanders—small balloons inserted under the skin to grow extra tissue before surgery so there's enough skin to cover the new wounds.

If you ask the families, the answer is more complicated. The medical advances gained from the Binder surgery helped save the Banda twins a decade later. But that's cold comfort to a mother whose children never got to grow up.

Key Takeaways from Carson’s Surgical Career

- Technique over Outcome: The 1987 surgery was a "technical success" because it proved the method, even if the clinical outcome for the patients was poor.

- 3D Modeling: Carson was an early adopter of using 3-D imaging to map out surgeries before making the first incision.

- The Power of Risk: These surgeries weren't performed because success was guaranteed; they were performed because, without them, the twins had a 0% chance of a normal life.

Practical Insights for Today

The story of Ben Carson and conjoined twins teaches us a lot about the ethics of modern medicine. When we see "miracle" headlines today, it's worth remembering that the recovery process is often a lifelong marathon, not a sprint.

If you’re researching this for a project or just out of curiosity, look for the peer-reviewed follow-ups, not just the initial press conferences. Medicine moves fast, but the human impact takes years to settle.

👉 See also: High Protein Dessert Recipes: What Most People Get Wrong About Healthy Sweets

Actionable Next Step: To see how far we've come since 1987, look up the 2020 separation of the Bibi twins in Turkey or the Canagueral twins. You'll notice that the use of Virtual Reality (VR) and 3D printing—technologies Carson helped pioneer the early versions of—are now the gold standard for preventing the neurological damage that the Binder twins suffered.