You’re probably doing it wrong. Honestly, most people are. You walk into any commercial gym and see someone grabbed a pair of fifty-pounders, hunched over like they’re looking for a lost contact lens, and started yanking the weights toward their chest with all the grace of a lawnmower pull-start gone bad. Their hips are rocking, their lower back is rounded, and their biceps are doing 90% of the heavy lifting. This is exactly why bent over rowing with dumbbells has a reputation for being "tough on the back" when it should be the gold standard for building a thick, powerful posterior chain.

It’s a foundational movement. It’s also a technical nightmare if you don't respect the physics.

Most lifters treat the row as a secondary thought after benching, but your back is a massive, complex network of muscles—latissimus dorsi, rhomboids, trapezius, rear deltoids—that requires more than just "pulling stuff." If you want that V-taper or just want to stop your shoulders from rolling forward after ten hours at a desk, you need to master the nuance of the dumbbell row. It’s not just about moving weight from point A to point B. It’s about tension, leverage, and not blowing out a disc in the process.

The Biomechanics of the Perfect Row

Let’s talk about the "hip hinge." If you can't hinge, you can't row. Period. When you perform bent over rowing with dumbbells, your hamstrings and glutes act as the anchor. You aren't just leaning over; you are pushing your hips back while keeping a neutral spine. Dr. Stuart McGill, a world-renowned expert in spine biomechanics, often emphasizes the "shortening" of the spine under load. If you round your back, you’re putting immense shear force on your lumbar vertebrae.

Keep your chest up. Not "pointing at the wall" up, but "proud."

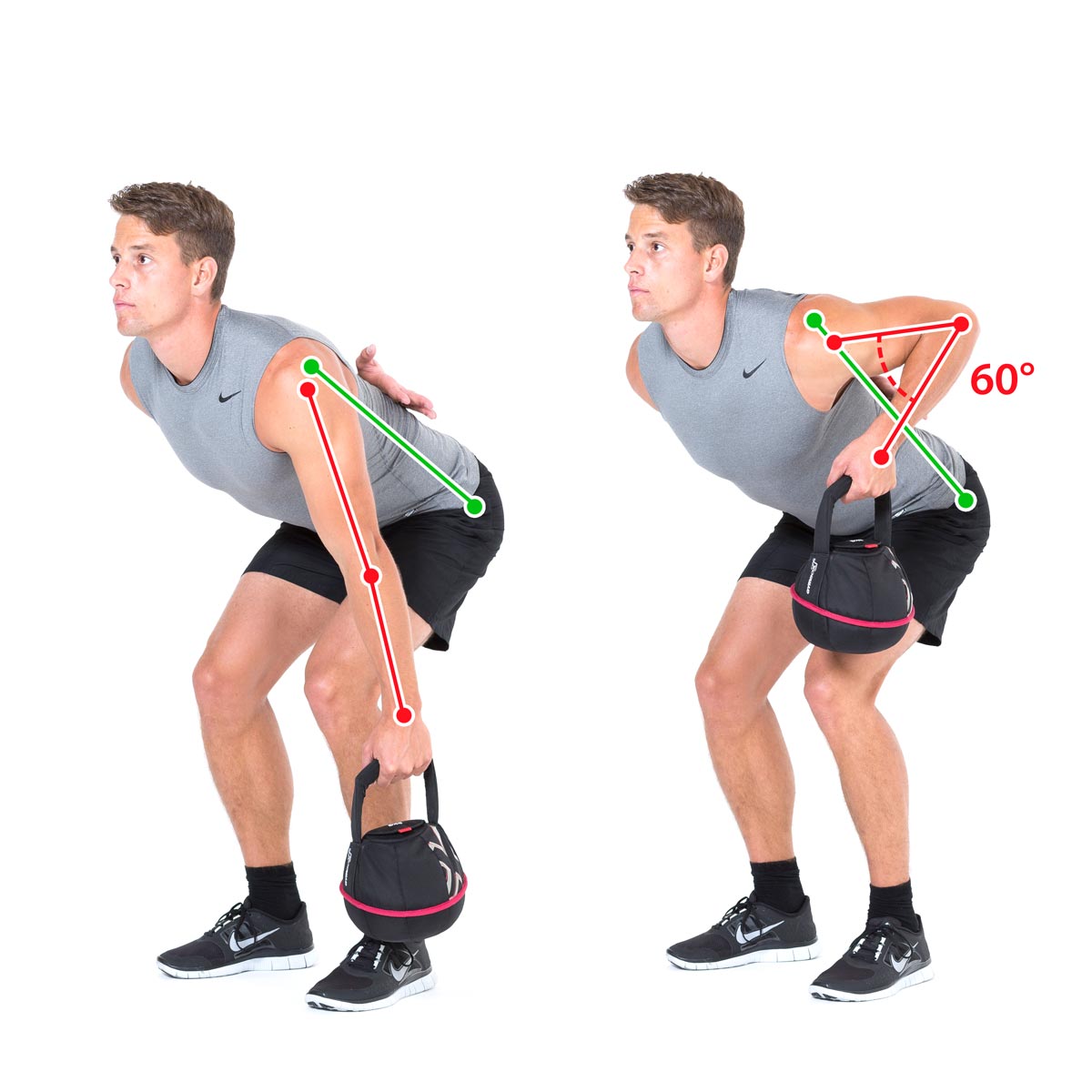

Your torso should be somewhere between 45 degrees and parallel to the floor. A lot of old-school bodybuilders swear by the 90-degree parallel row, but for most people with average hamstring flexibility, a slightly higher angle—around 15 to 30 degrees above parallel—is safer and allows for better lat engagement. When you pull, think about your elbows. Don't think about your hands. Your hands are just hooks. If you focus on pulling the dumbbell to your hip rather than your ribcage, you'll feel the lats kick in immediately.

Stop Making These Three Mistakes

The "T-Rex" Pull: This is where you pull the weight straight up to your armpit. It’s all biceps and upper traps. It looks silly. It feels worse. Instead, pull the dumbbell in a slight arc toward your waist. This engages the lower fibers of the lat.

The Ego Bounce: We’ve all seen it. The guy using 100-pound dumbbells who has to jump his whole body up just to get the weight moving. If you have to use momentum, the weight is too heavy. You’re training your ego, not your rhomboids. A real row involves a controlled eccentric (the lowering phase). If you’re just dropping the weight, you’re missing out on half the muscle-building potential.

Neck Cranking: Stop looking at yourself in the mirror. Seriously. When you crane your neck up to check your form, you’re pulling your cervical spine out of alignment. Look at a spot on the floor about three feet in front of you. Keep that neck tucked.

Variations That Actually Matter

You don't have to just stand there with two weights. In fact, variety is how you bypass plateaus.

The Three-Point Row (Single Arm)

This is arguably the king of all rows. By placing one hand on a bench, you create a tripod of stability. This allows you to go significantly heavier without your lower back being the limiting factor. Because your core has to fight the rotational pull of the weight, it’s also a secret oblique workout. National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) research suggests that unilateral (one-sided) training can help correct muscle imbalances that lead to injury.

📖 Related: Sunscreens for Acne Prone Skin: Why Your SPF is Probably Breaking You Out

The Chest-Supported Dumbbell Row

If your lower back is fried from deadlifts or you just have a history of tweaks, use an incline bench. Set it to about 45 degrees, lay face down, and row. This completely removes the "cheating" element. You can't bounce. You can't use your legs. It’s pure back isolation. It’s humbling because you’ll probably have to drop your usual weight by 20%, but the pump is incomparable.

The Renegade Row

This is for the "functional fitness" crowd, but it has its place. You’re in a plank position with your hands on the dumbbells. You row one side while balancing on the other. It’s less about back mass and more about "anti-rotational" core strength. Just don't be the person clanking the weights loudly in a quiet gym.

Why Your Grip is Failing Before Your Back

It’s frustrating. Your back feels like it could go for five more reps, but your forearms are screaming and the dumbbell is slipping. This is the great debate: to strap or not to strap?

Honestly? Use the straps.

If your goal is hypertrophy (muscle growth) of the back, don't let a weak grip hold you back. While it’s good to build forearm strength, bent over rowing with dumbbells is a back exercise. If you’re doing your heavy sets, wrap up. Save the raw grip work for your warm-ups or dedicated carry exercises.

👉 See also: Military diet for 3 days: What actually happens when you eat hot dogs and ice cream to lose weight

Programming for Real Results

How often should you do this? Most high-level coaches, like Mike Israetel of Renaissance Periodization, suggest training the back 2 to 4 times a week for optimal growth. Since the back is a large muscle group, it can handle a lot of volume, but you have to be smart.

- For Strength: 3 sets of 5-8 reps. Focus on the three-point row where you can move the most weight.

- For Hypertrophy: 4 sets of 10-15 reps. Use the chest-supported variation to really feel the squeeze at the top.

- The Finisher: Try a "drop set." Start with a heavy pair, go to failure, immediately grab a lighter pair, and keep going. Your lats will feel like they’re on fire.

The Anatomy of the Pull

To truly master the row, you have to understand what’s happening under the skin. Your lats are the biggest players, but they don't work alone. Your rhomboids and middle traps are responsible for "scapular retraction"—that’s the fancy term for pinching your shoulder blades together. If you don't pinch at the top of the movement, you aren't fully shortening those muscles.

Think of it like this: The first half of the movement is the lats pulling the arm back. The second half is the traps and rhomboids squeezing the shoulder blade toward the spine. If you skip the squeeze, you're only doing half the work.

Actionable Steps to Improve Your Row Today

Ready to actually see some progress? Don't just read this and go back to your old habits.

First, video your set. Set your phone up on the side and watch your spine. Are you rounding? Is your head popping up like a turtle? Most people are shocked when they see their actual form versus what they "feel" they are doing.

Second, slow down the tempo. Spend two full seconds lowering the weight. At the bottom, let the weight stretch your lats for a split second before pulling again. This "stretch-mediated hypertrophy" is a major driver of muscle growth.

Third, fix your stance. If you feel unstable, widen your feet. A wider base gives you more leverage. If you’re doing the two-arm version, try a staggered stance (one foot slightly in front of the other) if it helps your lower back feel more secure.

Finally, prioritize the squeeze. At the top of every rep, try to hold the weight for a one-second count. If you can't hold it, it’s too heavy. This simple rule will transform your back development faster than any "secret" supplement ever could. The dumbbell row isn't a race; it's a grind. Treat it with the respect it deserves, and your reflection in the mirror will start looking a lot wider.