You open your brokerage app. You see a stock price—let's say it's Apple or Tesla—and it looks like a solid number. $220.50. You hit buy. Suddenly, the trade executes at $220.55. You feel slightly cheated, right? Honestly, most people just ignore those few cents, but if you're moving a lot of shares, those pennies turn into real rent money. This is the world of bid vs ask stocks, and it is the literal heartbeat of the market. It's the friction that keeps the gears turning, even if it feels like a hidden tax on your portfolio.

Market prices aren't static things. They are more like a constant, high-speed negotiation between people who are desperate to get out and people who are dying to get in.

The Push and Pull of the Spread

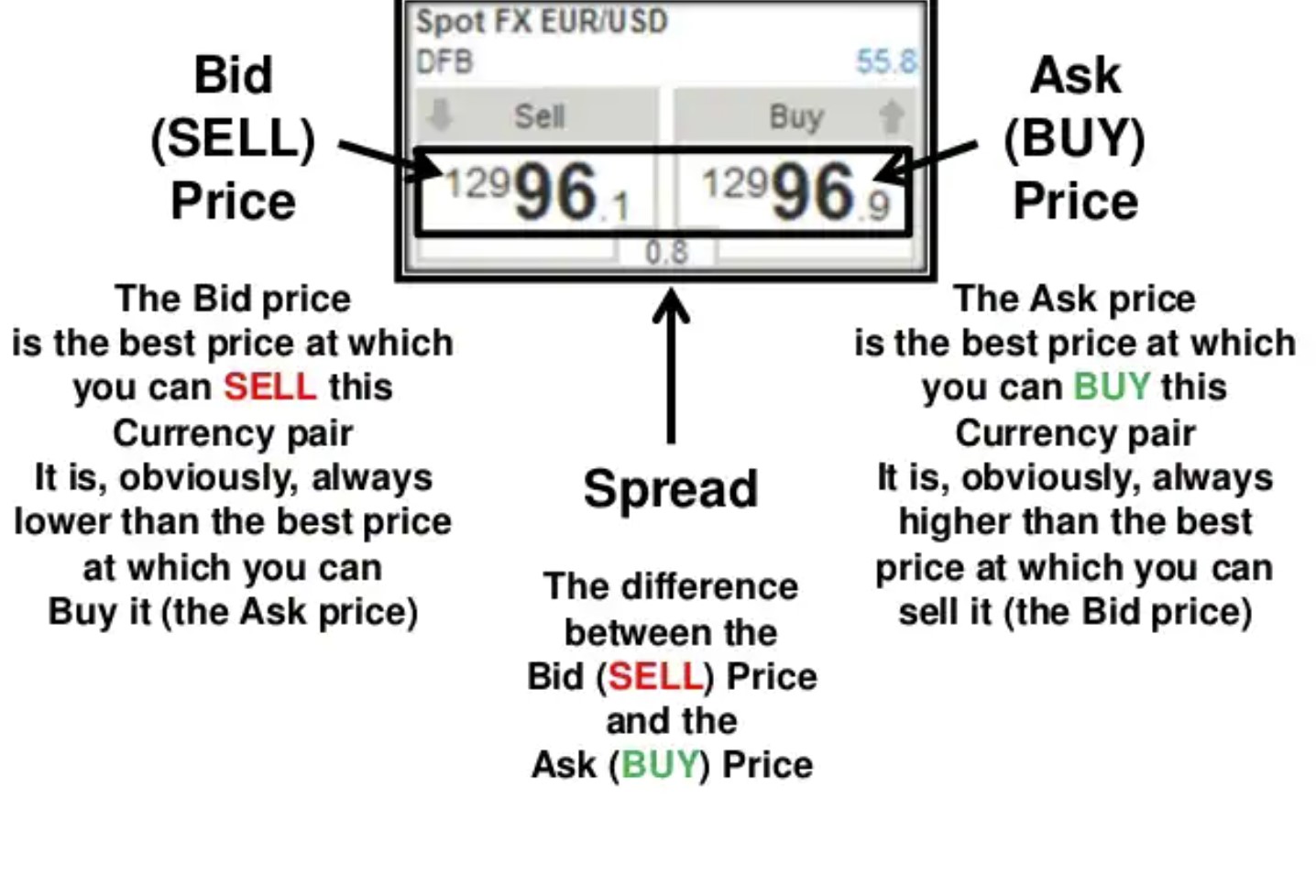

Think of the "bid" as the buyer's territory. This is the maximum price a buyer is willing to pay. On the flip side, the "ask" is the seller's turf. It’s the minimum they’ll accept to part with their shares. The gap between them? That’s the bid-ask spread. If you’ve ever traded a "thin" stock—maybe a small-cap biotech company or a weird penny stock—you’ve seen spreads that are wide enough to drive a truck through. In highly liquid stocks like SPY (the S&P 500 ETF), the spread is usually just a penny.

Why does this matter? Because the moment you buy at the "ask" and sell at the "bid," you are technically losing money. You start in the red.

💡 You might also like: Why the UPS PeriShip Global Shipping Agreement Changes Everything for Cold Chain Logistics

Market makers are the invisible hand here. Firms like Citadel Securities or Virtu Financial basically live in this gap. They provide liquidity by constantly posting bids and asks. They take the risk of holding the stock, and in exchange, they pocket that tiny difference. It sounds like peanuts, but when you process millions of trades a second, those peanuts build skyscrapers.

Market Orders vs. Limit Orders: The Great Trap

Most beginners use market orders. It’s easy. It’s fast. You just want the stock now. But using a market order in the context of bid vs ask stocks is basically giving the market permission to take the worst available price.

If the "ask" is $50.05 and the "bid" is $49.95, a market buy order will fill at $50.05. You just paid a premium for speed.

Smart traders—the ones who actually keep their gains—almost exclusively use limit orders. A limit order lets you pick your price. You tell the broker, "I will not pay a cent more than $50.00." Your order sits there on the bid side. You might not get filled immediately. You might not get filled at all if the stock moons. But you aren't getting "slippage," which is the industry term for that annoying price creep.

Why Spreads Blow Out During Volatility

Everything changes when the market panics. Remember the "Flash Crash" of 2010? Or even the wild swings during the early 2020 lockdowns? When uncertainty hits, market makers get scared. They don't know where the price is going, so they protect themselves by widening the spread.

- In normal times: Bid $100.00 / Ask $100.01

- In a crisis: Bid $98.50 / Ask $101.50

If you hit "Market Buy" during a period of high volatility, you could end up paying 2% or 3% more than the "last price" you saw on your screen. This is where "stop-loss" orders can actually ruin your life. If you have a stop-loss set to sell when a stock hits $90, and the market gaps down, your broker might sell your shares at the next available "bid"—which could be $85. You just lost an extra $5 per share because the spread widened into an abyss.

The Role of Liquidity

Liquidity is just a fancy way of saying how easy it is to flip a stock for cash without moving the price. Big blue-chip stocks have massive liquidity. Thousands of people are bidding and asking at every possible price point.

But look at something like a municipal bond or a tiny micro-cap stock. There might only be three people interested in buying it today. If you want to sell 10,000 shares of a low-liquidity stock, you’ll eat through the "bid" levels quickly. You might sell the first 100 shares at $10.00, the next 500 at $9.90, and the rest at $9.50. This is why institutional investors (the big whales) have to hide their trades using "dark pools." They can't just dump everything onto the public bid/ask spread without tanking the price.

Understanding the "Level 2" Screen

If you really want to see the bid vs ask stocks battle in real-time, you need Level 2 market data. Your standard Robinhood or E*TRADE screen usually shows Level 1—the best bid and the best ask. Level 2 shows you the "book."

It shows you that there are 5,000 shares wanted at $50.00, another 10,000 at $49.98, and so on. It also shows you who is making the market (identified by four-letter codes like CDEL for Citadel). When you see a massive "wall" of sell orders at a certain ask price, you know the stock is going to have a hard time breaking through that level. Traders call this "resistance." Conversely, a huge stack of bids creates "support."

💡 You might also like: Why Aventis Pharma Ltd Share Price Still Matters (and What It's Called Now)

Practical Steps to Stop Losing Money

You don't need to be a Wall Street quant to handle this better. You just need a little discipline.

First, stop using market orders for anything other than an absolute emergency. If a stock is moving so fast that you must use a market order, you're probably chasing a peak anyway. Set a limit order at the "midpoint"—right in between the bid and the ask. Sometimes a market maker will split the difference with you just to get the trade done.

Second, check the volume. If a stock trades less than 500,000 shares a day, be extremely careful. The spreads will be wider, and getting out will be harder than getting in. It’s like entering a room with a tiny door; it’s easy to walk in, but if everyone tries to leave at once, someone’s getting crushed.

Third, pay attention to the time of day. Spreads are usually widest right at the opening bell (9:30 AM EST) and right before the close. The "price discovery" process is messy in the first 30 minutes of trading. If you wait until 10:30 AM, things usually settle down, and the bid-ask spread tightens up, giving you a fairer price.

The Reality of "Commission-Free" Trading

We all love $0 commissions. But remember: if you aren't paying for the product, you are the product. Most retail brokers make money through "Payment for Order Flow" (PFOF). They send your orders to market makers like Susquehanna or Citadel.

These market makers pay your broker for the privilege of seeing your trade first. They then execute your trade within the bid-ask spread. While the SEC mandates "best execution," there is a lot of gray area. You might get a "price improvement" of a fraction of a penny, but the market maker still walks away with a profit. It’s a trade-off. You get free software and no commissions, but you might be paying a tiny bit more on the spread than you realize.

Final Actionable Insights

To master the spread and protect your capital, implement these rules immediately:

Always use Limit Orders. Even if you set your limit price a few cents above the current ask to ensure a fill, it protects you from "fat finger" errors or sudden spikes that could drain your account.

Avoid trading during the first 15 minutes of the market session. The volatility makes bid-ask spreads unpredictable and usually wider than they need to be.

Calculate the spread as a percentage. If a stock is $1.00 and the spread is $0.05, you are down 5% the moment you buy. That is a massive hurdle to overcome just to break even. Stick to stocks where the spread is a negligible fraction of the share price.

Monitor the "Size" next to the Bid/Ask. If you see a Bid of $50.00 (10) and an Ask of $50.10 (100), it means there are only 1,000 shares (10 x 100-share lots) wanted at $50, but 10,000 shares for sale at $50.10. This imbalance suggests the price might head lower because the "sell-side" pressure is much heavier.

Understanding the mechanics of the bid and the ask turns you from a gambler into a technician. It is the difference between blindly throwing money at a screen and actually participating in a professional marketplace. Stop looking at the "price" and start looking at the "negotiation."