Ever seen a version of Eric Cartman wearing a white taqiyah? If you grew up in Kuwait during the early 2000s, you probably did. While Western audiences were busy watching Stan, Kyle, Kenny, and Cartman get into increasingly R-rated trouble, a very different version of that same aesthetic was taking over Middle Eastern television. It was called Block 13.

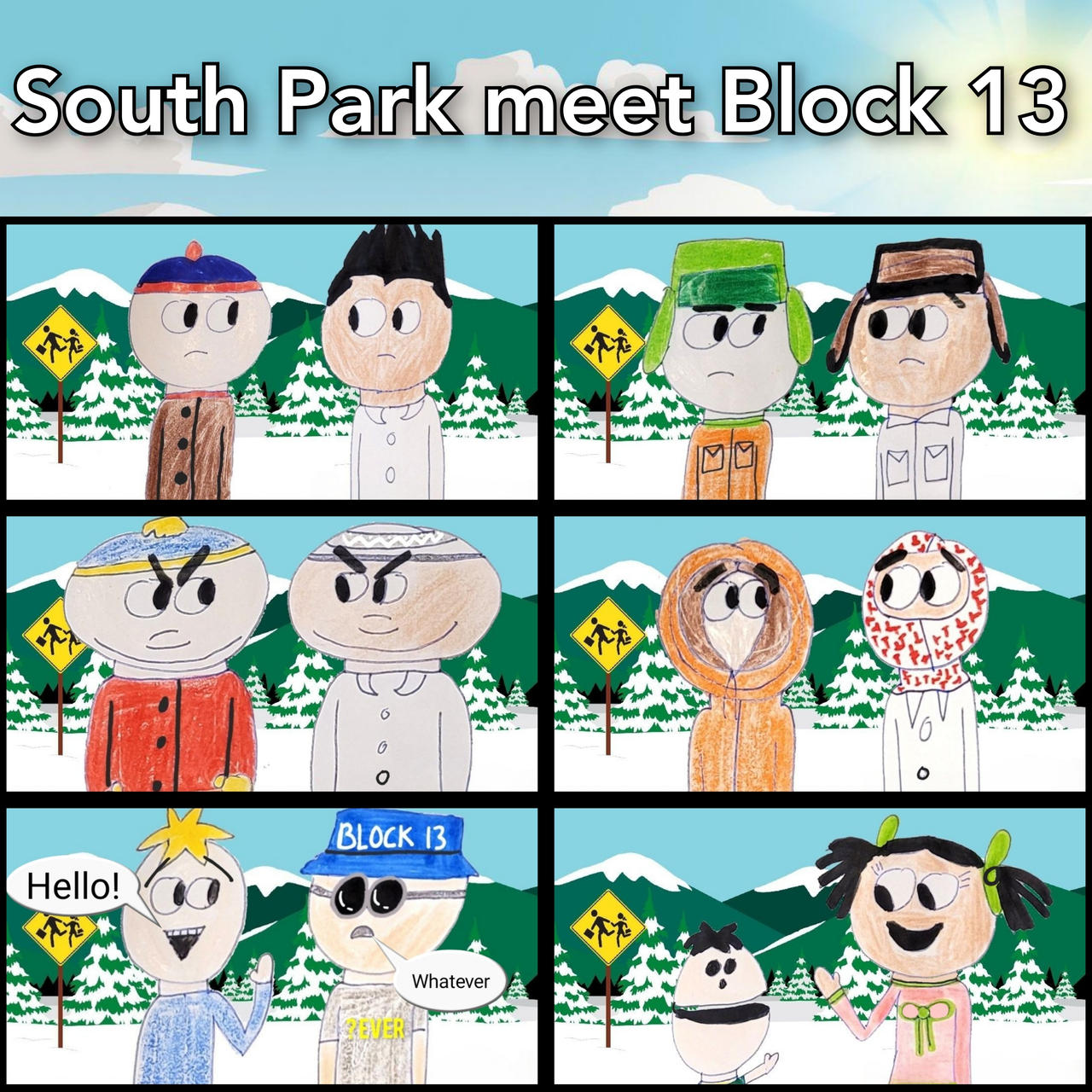

Most people look at a screenshot of Block 13 South Park side-by-side and assume it's just a lazy, low-budget ripoff. Honestly, at first glance, it is. The character designs are almost identical. The choppy, paper-cutout animation style is a direct lift. But the story behind why it exists—and how it became a cultural staple in the Gulf—is way more interesting than just some "shameless clone" narrative.

The Birth of the Arab South Park

So, here's the deal. By the late 90s, South Park was a global phenomenon, but it was also a massive headache for censors. In Kuwait and much of the Middle East, the show was eventually banned. The crude humor, the constant poking at religion, and the generally NSFW nature of Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s brainchild didn't sit well with local values.

But there was a vacuum. People liked the look. They liked the idea of a show about kids being kids.

Enter Nawaf Salem Al-Shammari. In 2000, he launched Block 13 on Kuwait Television. It wasn't some underground, bootleg project sold on the back of trucks; it was a primetime hit that aired during Ramadan. Imagine that for a second. The holiest month of the year, and families are sitting down to watch a show that looks exactly like the most profane cartoon in America.

Except, it wasn't profane. Not even a little bit.

How Block 13 Flipped the Script

The most fascinating thing about Block 13 South Park is how it kept the "skeleton" of the original but completely replaced the "soul." It’s an unlicensed adaptation, sure, but it’s more like a localized remix.

Take the characters. You've got your "Fab Four" equivalents:

👉 See also: Evil Exes Scott Pilgrim: Why They Aren't Actually Who You Think

- Abboud: He's the Cartman of the group. He’s chubby and loves being the center of attention, but instead of being a sociopathic bigot, he’s just a bit of a brat. He wears a white gahfiya (taqiyah).

- Hammoud: The "cool," well-mannered one. He’s basically Stan Marsh if Stan never had an existential crisis and always listened to his dad.

- Azzouz: This is the Kyle Broflovski stand-in.

- Saloom: The Kenny. This is the best part—instead of an orange parka, he wears his father’s red keffiyeh wrapped around his face. It muffles his speech just like Kenny, and he constantly gets into absurd accidents.

The humor wasn't about swearing or killing celebrities. Instead, Block 13 focused on "educational entertainment." It tackled local issues like school life, Kuwaiti traditions, and social etiquette. It was family-friendly. It was safe. It was, in many ways, the polar opposite of what South Park stands for.

Why the "Ripoff" Tag is Kinda Complicated

Is it a clone? Yes. The creators didn't have the rights. They took the visual language of Comedy Central’s biggest hit and used it to sell a totally different product.

But in the world of global media, "cloning" is often how new industries start. Block 13 was the first animated TV series ever produced in the Persian Gulf region. That’s huge. It proved there was a market for local animation. Before this, kids in the region were mostly watching dubbed Japanese anime or American imports.

There's even a theory among hardcore fans that South Park eventually noticed. In the 2001 episode "Osama bin Laden Has Farty Pants," there’s a scene with Afghan versions of the main characters. Some think this was a subtle jab back at the Kuwaiti show that had debuted just a year earlier.

The Mystery of the Season 3 Finale

The show ran for three seasons, ending in 2002 with 45 episodes. But if you try to find the whole thing online today, you’re going to run into a wall.

📖 Related: Why Surviving R Kelly Episodes Still Haunt the Music Industry Today

Most of the series is documented on YouTube, but the Season 3 finale is essentially "lost media." The director, Al-Shammari, once posted a video saying the episode wasn't about one specific thing but a collection of events. Despite that, a full, high-quality copy has never surfaced. It’s one of those weird internet mysteries that keeps the Block 13 South Park conversation alive in niche corners of Reddit.

In 2022, a spiritual successor called Street 13 (Shar’e 13) popped up, involving many of the original creators. It shows that even decades later, the "Block 13" brand still has weight.

What You Can Learn From the Block 13 Legacy

If you’re a creator or someone interested in how culture travels, this show is a case study. It proves that a "bad" idea (copying a famous show) can actually serve a legitimate purpose if you localize it correctly.

Actionable Takeaways for Content Strategy:

- Context is King: You can take a successful format from one niche or culture and "re-skin" it for another, as long as you understand the local values. Block 13 succeeded because it spoke Kuwaiti, not just because it looked like South Park.

- Identify the Vacuum: The creators saw a ban as an opportunity. When a popular product is removed from a market, people still want the feeling of that product.

- Iterate on the "Why": Don't just copy the look; change the purpose. Block 13 swapped satire for social lessons, making it indispensable for its specific audience during Ramadan.

If you want to see it for yourself, hunt down the theme song on YouTube. Even without knowing Arabic, you'll recognize the energy. It’s a bizarre, fascinating piece of television history that reminds us that sometimes, the most interesting things happen when the world tries to make its own version of a "block" we already know.

Check out the early episodes on the Internet Archive or YouTube to see the evolution of the animation—it’s a trip.