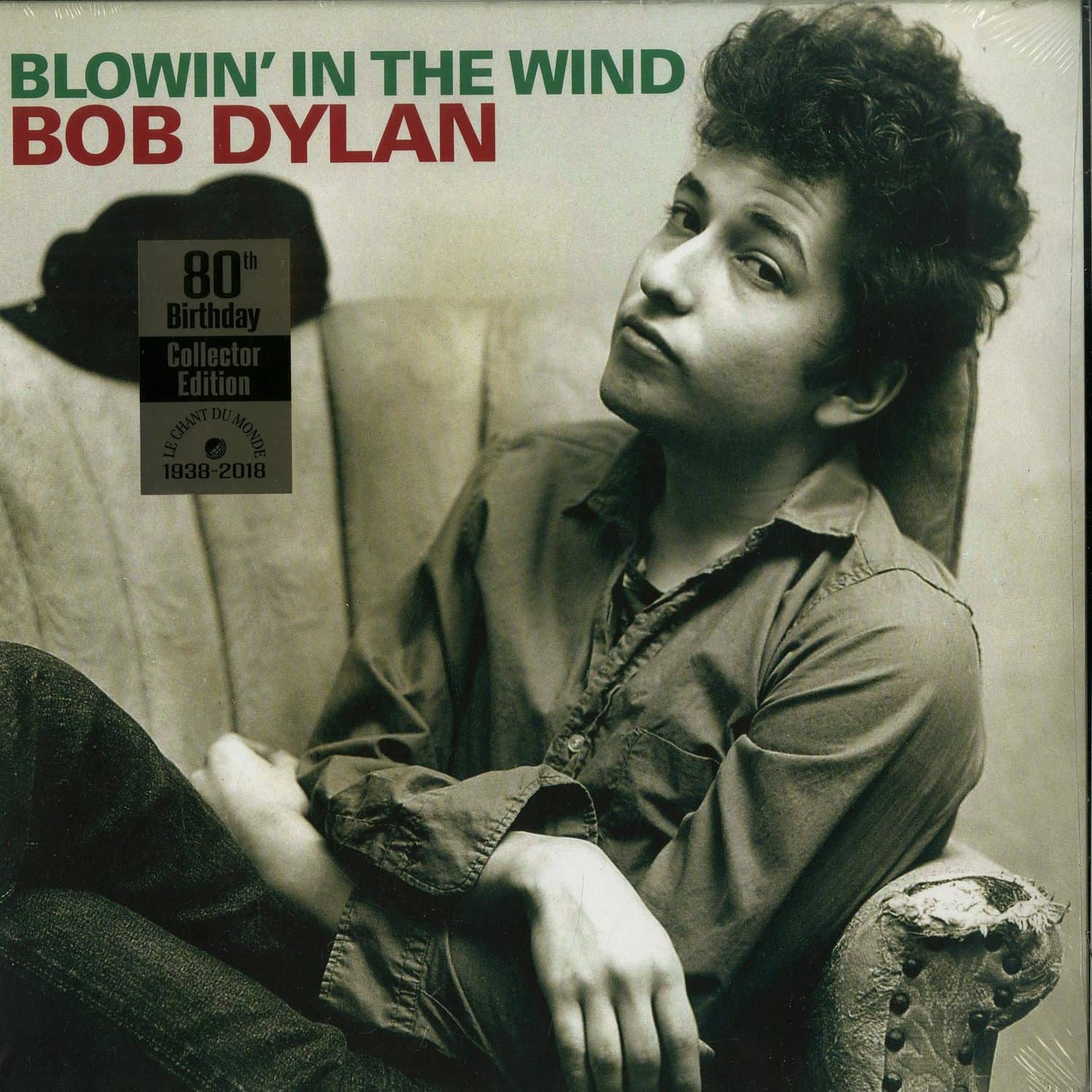

Honestly, if you ask most people about the 1960s, they’ll probably hum a few bars of Blowin' in the Wind and tell you it’s the ultimate protest song. It’s the anthem of a generation. It’s the "I Have a Dream" of folk music. But if you actually talk to Bob Dylan, he might give you a look that says you’ve missed the point entirely.

The song is everywhere. It’s been sung by popes, presidents, and kids in middle school choir. Yet, the story of how it was born in a cramped Manhattan cafe and how it actually works as a piece of poetry is way weirder than the history books usually let on.

The Ten-Minute Myth and the Greenwich Village Ghost

There’s this legend that Dylan sat down at The Commons (a cafe on MacDougal Street) and scribbled the whole thing on a napkin in ten minutes. Dylan himself has pushed this story. "I wrote it in ten minutes," he’s said more than once.

But here is the thing: songs like that don't just fall out of the sky.

The melody wasn't even "new." Not really. Dylan basically lifted the tune from an old African-American spiritual called "No More Auction Block." It was a song sung by former slaves who fled to Canada after 1833. Dylan was hanging out with Delores Dixon of the New World Singers at the time—she used to sing "No More Auction Block" at Gerde’s Folk City.

✨ Don't miss: Married at First Sight USA Season 4: Why Miami Was the Show's First Real Mess

Dylan heard it, liked it, and essentially poured his own lyrics into that historical mold.

Why the melody matters

- The "Folk Process": Pete Seeger used to call this "plagiarism" in a joking way, but in the folk world, it’s just how things worked. You take an old vessel and put new wine in it.

- Subconscious Weight: Because the melody came from a slave song, it carried a ghostly, heavy weight even before Dylan opened his mouth to sing about "how many years some people can exist before they're allowed to be free."

When he first performed it at Gerde's on April 16, 1962, it only had two verses. He hadn't even written the middle one yet. So much for the "ten-minute masterpiece" being finished in one go.

Blowin' in the Wind: The Answer That Isn't an Answer

The biggest misconception about Blowin' in the Wind Bob Dylan is that it’s a song of "solutions." People treat it like a political manifesto. But if you look at the lyrics, they’re just questions. Nine of them.

- How many roads?

- How many seas?

- How many deaths?

Dylan never actually gives you a "yes" or "no." He says the answer is "blowin' in the wind." That is incredibly frustrating if you're looking for a policy change, but it’s brilliant if you’re an artist.

The Ambiguity Trap

Is the answer "in the wind" because it's obvious? Like, right in front of your face? Or is it "in the wind" because it’s intangible and impossible to catch?

Mick Gold, a critic who followed Dylan’s early career, called it "impenetrably ambiguous." Dylan didn't want to be a leader. He didn't want to be the "voice of a generation." He was 21 years old and trying to figure out how to write a song that sounded as old as the Bible. He used images from the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Joel. He wasn't looking at the 1962 newspaper as much as he was looking at the human soul.

How Peter, Paul and Mary Changed the Game

We tend to forget that Dylan’s own version wasn't the one that made the song a global phenomenon. His second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, was great, but it was a bit... scratchy. A bit raw.

Then came Peter, Paul and Mary.

They were managed by Albert Grossman, who also managed Dylan. Grossman was a shark. He knew a hit when he heard one. He gave the song to the trio, and their version—polished, harmonic, and much "safer" for 1963 radio—sold 300,000 copies in the first week.

Suddenly, a song about cannonballs and death was sitting at #2 on the Billboard charts.

The Sam Cooke Connection

One of the coolest pieces of trivia about this track is what it did to Sam Cooke. Cooke, the king of soul, heard Peter, Paul and Mary's version on the radio. He was stunned. He was also a bit pissed off. He couldn't believe a young white kid from Minnesota had written a song that so perfectly captured the frustration of Black Americans.

Cooke started performing the song in his live sets, but more importantly, it pushed him to write "A Change Is Gonna Come." Without Dylan’s questions, we might never have gotten Cooke’s answer.

It’s Not Actually a "Protest" Song

Wait, what?

In a 1962 interview with Broadside magazine, Dylan said: "This here ain’t no protest song or anything like that, ’cause I don’t write no protest songs."

He was being cheeky, sure. But he was also being honest. To Dylan, a "protest song" was something that had a specific target—like a strike or a specific politician. Blowin' in the Wind is too big for that. It’s a song about the human condition.

He didn't want to be the guy with the picket sign. He wanted to be the poet on the hill.

The 2026 Perspective: Why It Still Ranks

You’d think a song from 1962 would feel like a museum piece by now. It doesn't.

Because Dylan kept the questions "vague," they never expire. We are still asking how many times a man can turn his head and pretend he doesn't see. We are still asking about the cannonballs.

The song has been covered by everyone: Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Dolly Parton, even Mavis Staples. Staples once said she couldn't understand how Dylan "knew" what they were feeling. That’s the magic. It’s a song that belongs to whoever is singing it.

What to do next

If you want to truly understand the DNA of this song, don't just listen to the Dylan version.

- Find a recording of "No More Auction Block" (Odetta does a haunting version). Listen to the melody.

- Then, pull up the Peter, Paul and Mary 1963 March on Washington performance.

- Finally, listen to Dylan’s 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue version, where he turns it into a crashing, electric rock song.

Seeing the evolution from a slave spiritual to a folk anthem to a rock-and-roll scream is the only way to see how the "wind" actually blows.