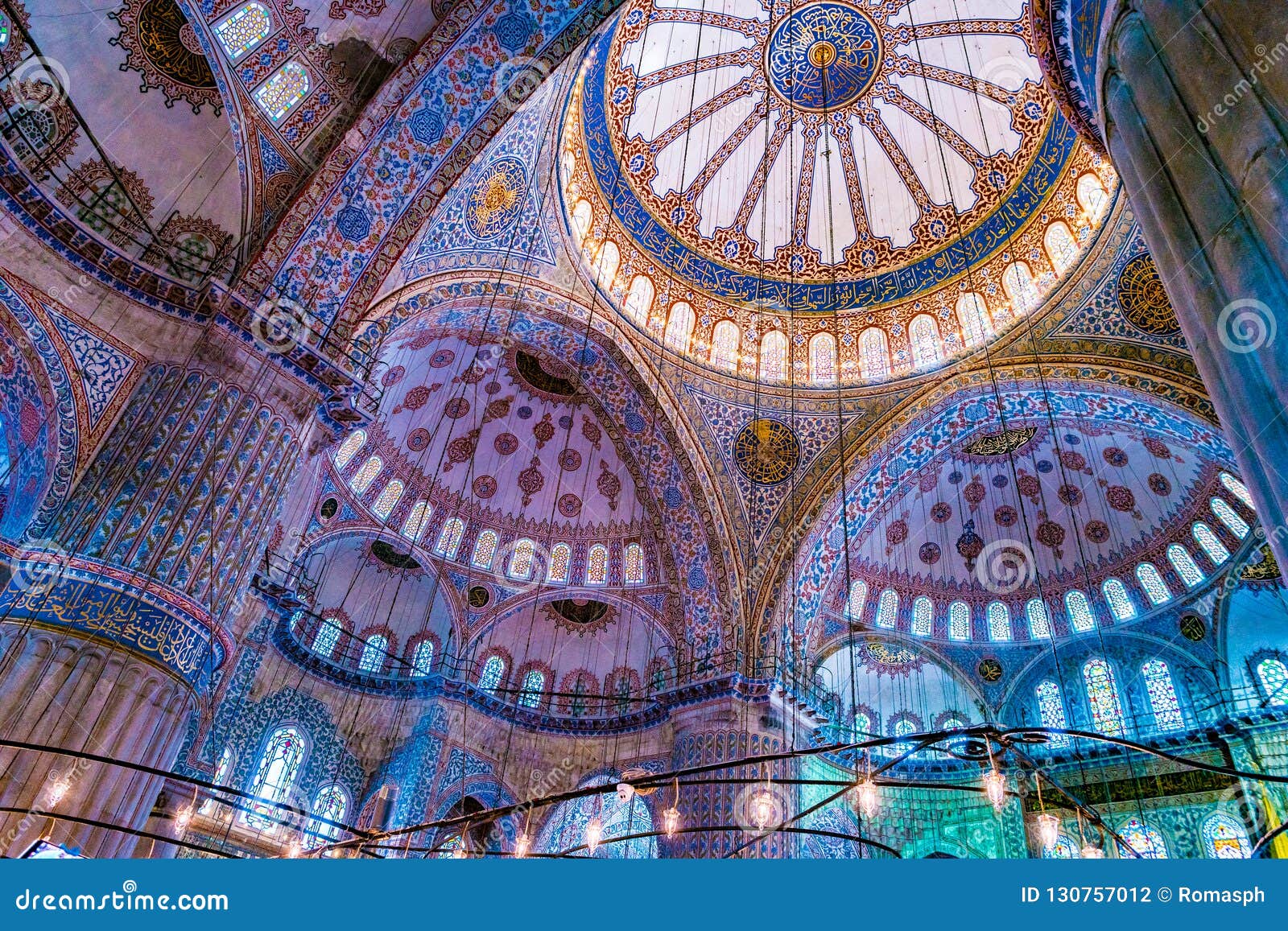

You walk in, and honestly, the first thing that hits you isn't the scale. It's the light. People call it the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, but once you’re standing on that massive red carpet looking up, you realize why "Blue Mosque" stuck. It’s a bit of a misnomer, though. The blue mosque istanbul interior isn't actually painted blue. It’s the glow.

Imagine twenty thousand handmade ceramic tiles.

Every single one of them was fired in the town of Iznik during the early 17th century. These aren't your hardware store tiles. We’re talking about intricate designs of lilies, carnations, and tulips—over fifty different tulip designs alone—that shimmer when the sun hits them through the 260 stained glass windows. Back in 1616, when Sultan Ahmed I finally opened the doors, this place was meant to outshine the Hagia Sophia. It was a bold move. Maybe even a little arrogant.

The Engineering Math Behind the Blue Mosque Istanbul Interior

Architecture is basically just controlled gravity. Sedefkar Mehmed Agha, the architect who studied under the legendary Mimar Sinan, had a massive problem to solve: how do you hold up a dome that’s 43 meters high without the walls just pancaking outward?

The answer is the "elephant feet."

That’s what locals call the four massive fluted columns that dominate the blue mosque istanbul interior. They are five meters in diameter. Just massive. If you look closely at these pillars, you’ll see they aren't just there for support; they are deeply integrated into the aesthetic, carved with calligraphy that makes them feel lighter than they actually are. The weight of the central dome is distributed through a series of smaller half-domes and smaller-still quarter-domes. It’s a cascading effect. From the outside, it looks like a mountain of lead and stone. From the inside? It feels like it’s floating.

✨ Don't miss: Le Mont Saint Michel Weather: What Most People Get Wrong

Those Famous Iznik Tiles

The tiles are the soul of the building. But there’s a sad bit of history here. During the construction, the Sultan actually mandated a fixed price for the tiles. As inflation hit and the cost of production rose, the quality of the later tiles started to dip. You can actually see this if you’re a nerd about it. The tiles on the lower levels are vibrant and sharp. The ones in the higher galleries? They’re a bit more faded, the glazes slightly thinner.

It’s a real-world lesson in what happens when you try to price-control an artist.

The color palette is dominated by cobalt blue, turquoise, and a very specific shade of tomato red that Iznik was famous for. This red is actually raised off the surface of the tile. If you could touch them (don't, the guards will lose it), you'd feel the texture. Most of the tile work is concentrated in the galleries, which are unfortunately often closed to the general public during restoration periods, but you can see plenty from the main floor.

Light, Ostrich Eggs, and Spider Webs

Look up at the chandeliers. They hang surprisingly low. They used to be covered in gold and gems, which have mostly disappeared into museums or private collections over the centuries. But there’s a weird detail most people miss. Inside the lamps, they used to place ostrich eggs.

Why? Because spiders hate them.

It’s an old trick. The eggs give off a scent (undetectable to us) that keeps spiders from spinning webs. It kept the blue mosque istanbul interior clean for centuries without needing a 40-foot ladder every Tuesday. Today, you’ll mostly see glass globes, but the historical cleverness of it still sticks with you.

The light itself is a masterpiece. The windows were originally a gift from the Signoria of Venice to the Sultan. Most of those original Venetian windows are gone now, replaced by modern versions that aren't quite as magical, but the way they filter the Istanbul sun still creates that famous blue atmosphere. It’s best to visit in the morning. When the sun is at a certain angle, the light hits the upper galleries and reflects off the blue-tinted tiles, making the whole air feel like it’s underwater.

The Mihrab and Minbar

The focal point of the interior is the Mihrab. This is the niche that points toward Mecca. It’s carved out of finely sculpted marble, featuring a stalactite niche and a double inscriptive panel above it. To its right is the Minbar, or the pulpit.

This thing is a feat of marble carving. It’s shaped like a narrow staircase leading up to a small tower. On a Friday at noon, the Imam stands here to deliver his sermon. The acoustics are designed so that even before microphones, the Imam's voice would bounce off those domes and reach the very back of the room. It’s an analog surround-sound system.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Carpet

You’ll notice the carpet is incredibly soft. It’s replaced regularly because millions of people walk on it every year. It’s usually a deep red or green, designed with small rectangular patterns. These aren't just for decoration. Each rectangle is a "prayer spot" for an individual worshiper.

When you see the blue mosque istanbul interior during prayer time (when tourists are shuffled out), the symmetry is perfect. Everyone lines up exactly on the grid of the carpet. It’s a level of organization that contrasts beautifully with the chaotic swirl of the tile patterns on the walls.

Also, it’s worth noting that the mosque is a living building. It’s not a museum like the Hagia Sophia was for so long. People pray here five times a day. This means the interior always smells faintly of rosewater and, honestly, a lot of socks. It’s a human place. It’s not a sterilized historical site.

The Calligraphy of Seyyid Kasim Gubari

You can't talk about the interior without mentioning the writing on the walls. The calligraphy was done by Seyyid Kasim Gubari, who was considered the greatest calligrapher of his time. These aren't just "verses." They are massive architectural elements. Many of them are verses from the Quran or names of the Caliphs.

They are framed by the "muqarnas"—those honeycomb-like carvings in the corners of the domes. The muqarnas serve a dual purpose. They look like dripping honey, but they actually help transition the square base of the building into the circular base of the dome. It’s where math meets art in a very literal way.

Why the Six Minarets Matter Inside

Technically, the minarets are an exterior feature. But they changed the interior experience. Because there are six of them, the mosque had to have a massive courtyard to balance the weight and the visual profile. This courtyard acts as a "buffer zone" for your eyes. By the time you walk through the doors and see the blue mosque istanbul interior, your eyes have adjusted to the scale.

The Sultan was actually criticized for the six minarets. At the time, only the mosque in Mecca had six. He ended up paying for a seventh minaret to be built in Mecca just to quiet the critics and show he wasn't trying to outdo the holiest site in Islam.

📖 Related: Carnival Cruise Donation Request: How to Actually Get a "Yes" from the Fun Ships

Practical Insights for Seeing the Interior

If you want to actually see the details I've mentioned, don't just stand in the middle.

- Look behind you: The view of the entrance door from the inside is often more beautiful than the view of the Mihrab.

- Check the corners: The best tile work is often tucked away in the corners near the elephant feet, where the light is lower and the colors seem deeper.

- Time it right: Avoid the hour after the Call to Prayer. The mosque is closed to tourists then. Aim for mid-morning, around 9:00 AM or 10:00 AM.

- Dress the part: It sounds obvious, but if you don't have a headscarf (for women) or long pants (for men), you’ll spend your whole time focusing on the blue polyester robe they lend you at the door rather than the architecture.

The blue mosque istanbul interior is a lesson in persistence. Sultan Ahmed died at age 27, only a year after the mosque was finished. He’s buried right outside in a tomb that’s also worth a look. He poured his entire legacy into these tiles and these domes. Even if you aren't religious, you can feel the weight of that ambition.

Next time you’re there, look past the crowd of people taking selfies. Look at the transition from the red of the carpet to the blue of the tiles and then the gold of the calligraphy. It’s a color gradient designed in 1609 that still works perfectly in 2026.

Plan your visit for a Tuesday or Wednesday morning. These are statistically the least crowded days for the Sultanahmet district. If you want to see the tile work without the glare of the electric lights, go on a bright, slightly overcast day. The clouds act as a natural softbox for the stained glass, making the interior colors pop without the harsh shadows of direct sunlight.