March 1965. A lot of people like to say this is the exact moment Bob Dylan "sold out" or "went electric," but that’s honestly a bit of a lazy take. It’s way more complicated than that. When Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home hit the shelves, it didn't just change his career; it basically broke the mold for what a pop record was allowed to be.

Before this, you had "folk Dylan"—the guy with the harmonica rack and the protest songs—and you had the "British Invasion" bands doing catchy love songs. This album smashed those two worlds together with a sledgehammer. It’s half-electric, half-acoustic, and 100% weird in the best possible way.

Most fans today don't realize how much of a middle finger this album was to the purists. The folk scene in the early sixties was rigid. Like, really rigid. If you weren't singing about coal mines or social justice over a simple acoustic strum, you were considered a "traitor." Then Dylan shows up with a Fender Stratocaster and a bunch of session musicians, playing "Subterranean Homesick Blues" at a speed that felt like a caffeine overdose.

The Three-Day Blur in Studio A

Let’s talk about how this thing actually got made. It wasn't some months-long experimental project. It was fast. Brutally fast.

Dylan walked into Columbia’s Studio A in New York City on January 13, 1965. The first day was just him—solo acoustic stuff. But the next day, producer Tom Wilson brought in the cavalry. We're talking Bruce Langhorne on guitar, Al Gorgoni, and even Bill Lee (who, fun fact, is filmmaker Spike Lee’s dad) on bass.

👉 See also: A Killing in a Small Town Movie: Why This 1990 True Crime Classic Still Haunts Us

They didn't really rehearse.

Dylan would sit at a piano or pick up a guitar, show them the basic structure, and then they’d just go. "Subterranean Homesick Blues"? One take. "Maggie’s Farm"? One take. Think about that next time you hear a perfectly polished, over-produced pop song today. The energy on the electric side of the record (Side A) feels like it’s barely holding together, and that’s exactly why it works. It’s raw.

Why the "Folkies" Lost Their Minds

You’ve probably heard about the 1965 Newport Folk Festival where Dylan got booed. Well, Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home was the warning shot that everyone ignored.

The first track, "Subterranean Homesick Blues," is basically a proto-rap song. The lyrics are a dizzying stream of consciousness about drug busts, the "heat," and the absurdity of 1960s straight-laced culture. "Twenty years of schoolin' and they put you on the day shift." It was cynical, funny, and loud.

But then there's "Maggie’s Farm." People often interpret it as Dylan saying goodbye to the folk movement itself. He sings about not wanting to work for "Maggie" or her father or her mother anymore. He was tired of being the "voice of a generation" that everyone else wanted him to be. He just wanted to be a rock star, or a poet, or maybe just a guy who could play loud music without getting a lecture on "purity."

The Acoustic Side: Poetry in the Dark

If Side A was a riot, Side B was a fever dream. This is where the album gets really deep. Even though it's "acoustic," it isn't "folk" in the traditional sense. Gone are the songs about specific news events or historical figures. Instead, we got surrealist masterpieces.

- Mr. Tambourine Man: A lot of people think this is about drugs. Dylan says it isn't. It’s more of a prayer to the muse—a plea to be taken away from the "weariness" of the world. Bruce Langhorne’s electric guitar parts here (yes, there's a subtle electric guitar even on the "acoustic" side) are haunting.

- Gates of Eden: This one is dense. It’s Dylan at his most "Beat Poet" influenced. He’s riffing on William Blake and the idea that the only place where there’s no "wrong" is a place that doesn't actually exist.

- It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding): This is arguably the most powerful track on the album. It’s 15 verses of pure, unadulterated venom toward consumerism, religion, and the hollow promises of the American Dream. "Money doesn't talk, it swears." It still feels relevant in 2026.

- It's All Over Now, Baby Blue: The final track. It feels like a goodbye. It’s gentle but firm. Dylan was leaving his old life behind, and he was telling his fans they should probably do the same.

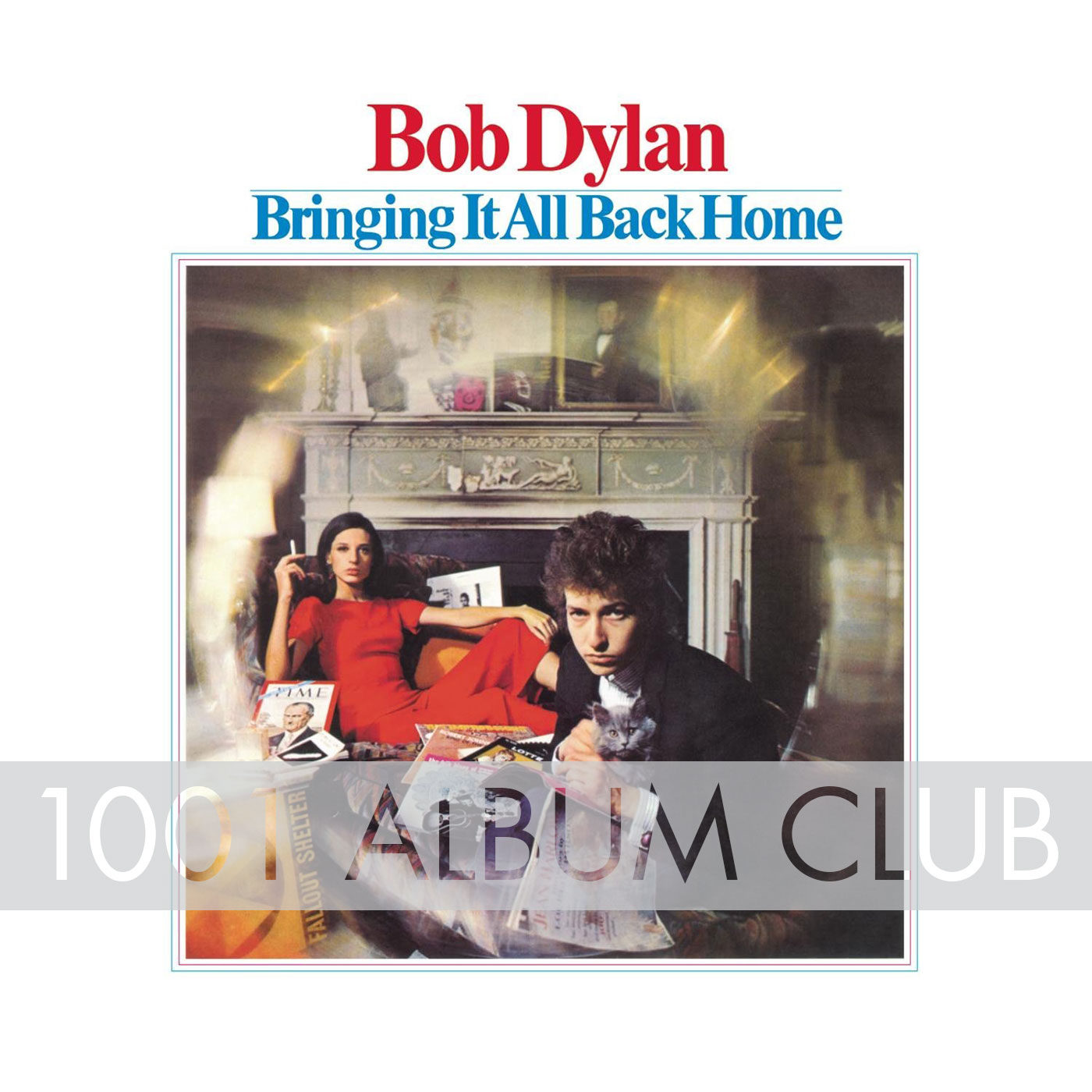

The Album Cover: More Than Just a Pretty Face

You can't talk about Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home without mentioning that cover. It’s iconic for a reason.

That woman in the red dress? That’s Sally Grossman, the wife of Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman. They’re sitting in the Grossman’s home in Bearsville, New York. If you look closely at the background, you’ll see a bunch of "Easter eggs." There’s a copy of Time magazine with LBJ on the cover, a Lotte Lenya record, and even Dylan's own previous album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, peeking out.

It was a deliberate image shift. He wasn't the dusty hobo from the Freewheelin' cover anymore. He was wearing cufflinks (a gift from Joan Baez, apparently). He looked like a sophisticated, slightly dangerous bohemian. He looked like the future.

Why It Still Matters Today

Honestly, music history is usually divided into "Before Bringing It All Back Home" and "After." It proved that rock music could have a brain. Before this, "serious" lyrics were for folk singers, and "fun" music was for rock bands. Dylan showed that you could have both.

The Beatles were listening. John Lennon famously said that Dylan "showed the way." Without this album, we probably don't get Rubber Soul or Revolver. We definitely don't get the Byrds, who took "Mr. Tambourine Man" and turned it into a #1 hit, officially launching the "folk rock" genre.

✨ Don't miss: James Taylor All Star Band: Why This Lineup Is The Secret To His Live Magic

What You Should Do Next

If you haven't listened to the album in a while—or ever—don't just play the hits.

- Listen to the stereo mix vs. the mono mix. The mono version has a punchiness that the stereo version lacks, especially on the electric tracks.

- Read the liner notes. Dylan wrote a sprawling, hallucinogenic poem on the back of the record that gives you a glimpse into his headspace at the time.

- Watch 'Don't Look Back'. The D.A. Pennebaker documentary covers the 1965 tour right after this album came out. It’s the perfect visual companion to the music.

The real takeaway from Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home isn't that Dylan changed his sound. It's that he gave himself permission to change. He refused to stay in the box the world built for him. In a world that constantly tries to categorize everything, that might be the most "punk" thing he ever did.

To truly appreciate the transition, listen to "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" from his previous work and then immediately play "Subterranean Homesick Blues." The distance between those two songs is the distance Dylan traveled in just one year. It’s staggering. Check out the 2025 remastered vinyl if you can find it; the low end on the bass tracks finally gets the room it deserves.

Practical Next Steps:

Start by listening to Side A (the electric side) at high volume to catch the chaotic interplay between the musicians. Then, transition to Side B in a quiet environment to focus on the intricate internal rhymes of "It's Alright, Ma." For a deeper dive, compare Dylan's original "Mr. Tambourine Man" with the Byrds' version to see how his "poetry" was translated into "pop."