It was 1966. Bob Dylan was at the absolute peak of his "thin wild mercury sound." He was skinny, fueled by high-octane nerves, and basically reinventing what a popular song could be every time he sat at a piano. Then came Just Like a Woman. It’s one of those tracks that feels like it’s been around forever, a staple of classic rock radio and "best of" lists, yet it remains one of the most polarizing entries in his massive catalog.

Is it a tender portrait of vulnerability? Or is it a condescending, maybe even misogynistic, takedown of a woman who flew too high?

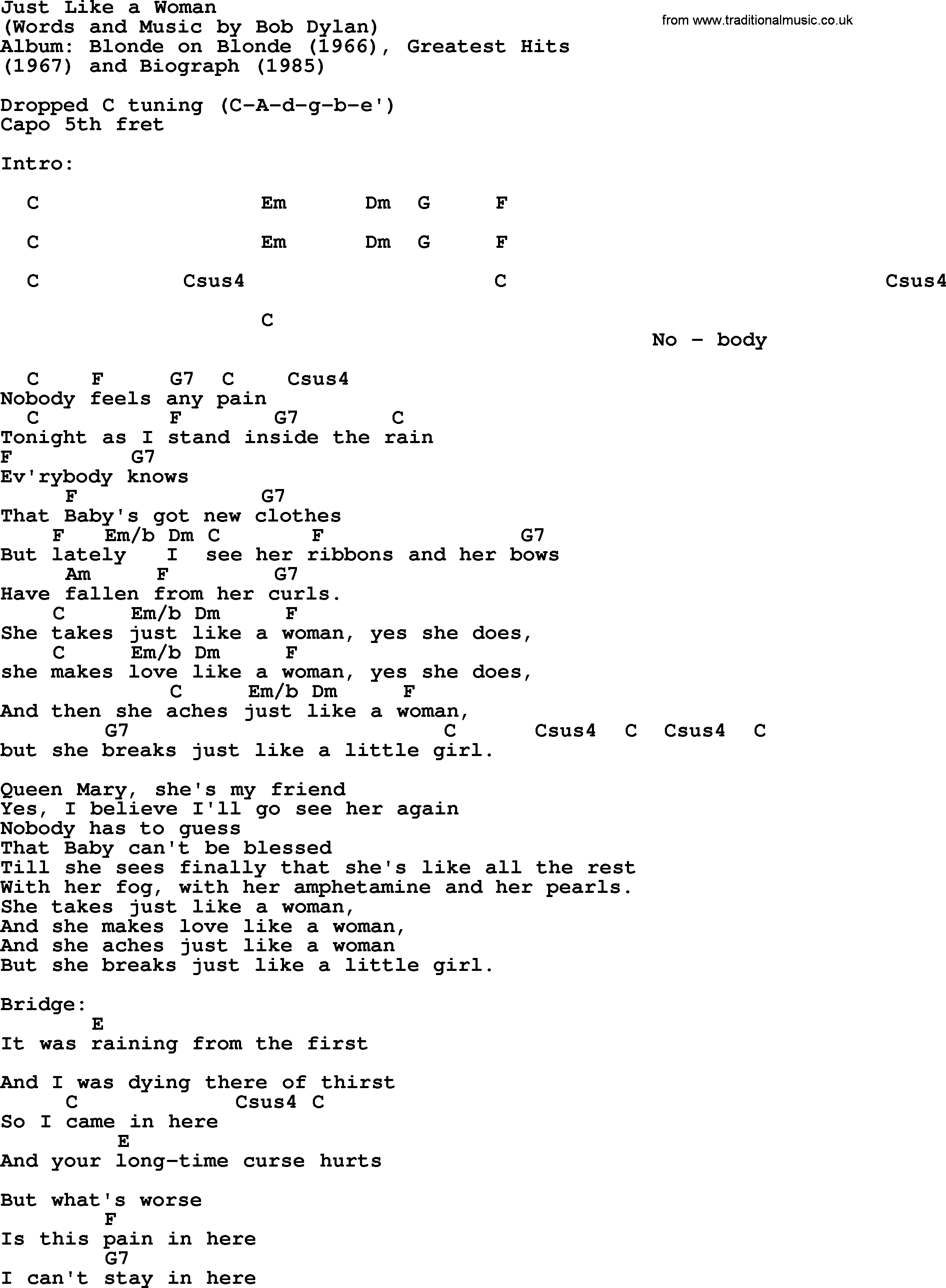

Honestly, it depends on who you ask and what day of the week it is. Recorded in the early morning hours in Nashville for the legendary Blonde on Blonde album, the song captures a specific kind of jagged heartbreak. It’s not a simple "I miss you" ballad. It’s complicated. It’s messy. It’s Dylan.

The Mystery of the "She"

People have spent decades trying to pin down exactly who Dylan was singing about. You've probably heard the rumors. The most common theory points directly at Edie Sedgwick, the "Poor Little Rich Girl" of Andy Warhol’s Factory scene.

👉 See also: Why The Railway Man Netflix Release Still Hits So Hard Today

The timeline fits. Sedgwick was a tragic figure—fragile, aristocratic, and caught in the crossfire between Warhol’s avant-garde world and Dylan’s burgeoning rock royalty. When Dylan sings about her "fog, amphetamine, and pearls," it’s hard not to see Edie. But Dylan is rarely that literal.

Some critics, like Robert Shelton, have suggested the song is a composite. It might be about Joan Baez. It might be about his future wife, Sara Lownds. It might even be a mirror he’s holding up to himself. Dylan has a habit of writing songs that seem to be about other people but are secretly about his own internal state.

Regardless of the muse, the lyrics paint a picture of someone who puts on a grand performance of adulthood and "womanhood" but eventually breaks down under the pressure. She takes just like a woman. She makes love just like a woman. But she breaks just like a little girl. That last line is the one that gets people riled up. It suggests a certain fragility that some find patronizing. Others see it as a moment of genuine empathy for someone who is clearly drowning.

Nashville, 4:00 AM, and the Search for the Sound

The recording of Just Like a Woman is a masterclass in "happy accidents." Dylan had moved the sessions from New York to Nashville because he wanted a smoother, more professional sound, but he brought his chaotic writing process with him.

The session musicians—the "Nashville Cats"—were used to charts and clear instructions. Dylan gave them neither. They’d sit around for hours while he tinkered with lyrics in the corner. Then, at three or four in the morning, he’d suddenly announce he was ready.

Take a close listen to the "Boots of Spanish Leather" style picking or the way the harmonica enters. It isn't perfect. It's human. Charlie McCoy’s guitar work and Kenneth Buttrey’s drumming provide this soft, pillowy cushion for Dylan’s voice, which—let's be real—was at its most nasal and expressive during this era.

Why the melody works

The song follows a fairly standard structure, but the way Dylan phrases the lines is what keeps it alive. He drags out the words. He spits some out. He almost sneers "Queen Mary" in a way that feels both mocking and weary. It’s a 4/4 time signature, but it feels like it’s swaying, almost like a waltz that lost its way.

The Gender Controversy: Misogyny or Masterpiece?

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Just Like a Woman became a lightning rod for feminist critique.

Critics like Marion Meade famously slammed the song, arguing that it defined womanhood through the lens of weakness and dependency. The idea that a woman’s "breaking" reduces her to a "little girl" is, on the surface, pretty dismissive. It positions the narrator as the observer, the "adult" in the room watching a child have a tantrum.

But there’s a counter-argument.

✨ Don't miss: Ludacris Get Back Lyrics: Why This 2004 Anthem Still Hits Different

Some listeners see the song as a critique of the roles women were forced to play in the 1960s. The "woman" in the song is performing. She’s wearing the pearls, she’s doing the "making love" bit, she’s playing the part society expected of a sophisticated lady. But it’s an act. When the mask slips, her true, vulnerable self—the "little girl"—is all that’s left.

Is Dylan mocking her? Or is he mocking the world that made her that way?

It’s probably a bit of both. Dylan wasn’t a saint, and his "breakup" songs from this period (Don't Think Twice, It's All Right, It Ain't Me, Babe) are often tinged with a "don't let the door hit you on the way out" vibe. However, there’s a sadness in Just Like a Woman that those other songs lack. There’s a sense that the narrator is just as broken as she is, he’s just better at hiding it.

The Cover Versions: From Nina Simone to Jeff Buckley

You know a song has legs when people from completely different genres try to tackle it.

- Nina Simone: Her version is arguably the most famous. She flips the script. When a Black woman in the late 60s sings these lyrics, the "breaking" feels less like a weakness and more like a weary exhaustion from a world that won't let her just be.

- Jeff Buckley: His live covers were ethereal. He emphasized the longing. In his hands, the song became a shimmering, reverb-drenched prayer.

- The Hollies: They did a version that Dylan allegedly hated. It was too "pop," too clean. It lost the grit.

Every cover reveals a different facet of the song. It’s like a diamond; you turn it a few degrees, and the light hits a different flaw or a different sparkle.

Why It Still Matters Today

In the era of "cancel culture" and hyper-awareness of gender dynamics, Just Like a Woman is a difficult listen for some. But art isn't always supposed to be comfortable.

The song captures a very specific, very raw human moment: the realization that someone you put on a pedestal is just as fallible and scared as you are. It’s about the end of an affair where nobody really wins. The "rainy-day women" and the "Queen Marys" are all just people trying to get through the night.

Musically, it’s a cornerstone of the folk-rock movement. Without this track, we don't get the introspective singer-songwriter boom of the 1970s. It gave artists permission to be specific, to be local, and to be mean-spirited in their songs if that’s what the truth required.

Technical Breakdown: The Nashville Sound

If you’re a gear head or a music student, the production on this track is worth a deep dive. Producer Bob Johnston did something radical: he let the tapes roll.

In the 60s, studios were often rigid. Johnston, however, encouraged the Nashville session players to interact with Dylan’s eccentricities. The result is a recording that feels "live" even though it was carefully tracked. The separation between the instruments is clean, but the vibe is loose.

- The Harmonica: Dylan’s solo at the end is iconic. It’s not technically "good" harmonica playing in a blues sense, but it’s emotionally perfect. It sounds like a sigh.

- The Bass: The bass line is melodic, almost carrying the tune as much as the guitar does.

- The Vocals: This is Dylan’s "Mercury" voice. It’s high, thin, and cuts through the mix like a hot knife.

Actionable Takeaways for Music Lovers

If you want to really understand the impact of Just Like a Woman, don't just stream it once and move on.

- Listen to the Mono Mix: Most people hear the stereo version, but the original mono mix of Blonde on Blonde has a punch and a cohesion that the stereo spread lacks. It feels more urgent.

- Compare the "Royal Albert Hall" 1966 Live Version: (Actually recorded at Manchester Free Trade Hall). Dylan plays it solo on the acoustic guitar. Without the band, the lyrics feel much more biting and much more intimate. It’s a different song entirely.

- Read the Lyrics Without Music: Treat it like a poem. Look at the internal rhymes ("ribbon" / "given" / "oblivion"). Notice how he uses "vague" and "plague." The wordplay is dense.

- Watch the Documentary "No Direction Home": Martin Scorsese’s doc covers this era perfectly. It gives you the visual context of what Dylan looked like and how the world reacted to him at this exact moment in time.

Just Like a Woman isn't a song that provides answers. It doesn't tell you how to feel about women, and it doesn't give you a roadmap for a successful relationship. Instead, it offers a snapshot of a moment in 1966 when the world was changing, and one man was trying to make sense of the chaos in his own head. Whether you love it or find it dated, you can't deny its staying power. It remains a ghost in the machine of American music, still haunting us sixty years later.

How to Explore Further

- Listen to the "Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge": This contains multiple takes of the song, allowing you to hear it evolve from a faster, almost garage-rock version into the ballad we know today.

- Explore Edie Sedgwick's Story: Read Edie: American Girl by Jean Stein to understand the tragic world Dylan was likely referencing.

- Study Nashville Session History: Look into the work of the "A-Team" session musicians to see how they shaped the sound of the 60s and 70s beyond just Dylan.

The next time you hear that opening guitar trill, listen for the "fog" and the "pearls." It's a journey into a specific kind of 1960s melancholy that few have ever captured since.