You’re sitting in a boardroom. The CEO stands up, clicks a laser pointer, and shows a slide of a pyramid. That’s the classic view. Orders flow down, reports flow up, and everyone knows their place. But then you look at a company like Valve—the people who made Half-Life—where there aren't really any bosses and people just move their desks toward projects they like. That’s the other side of the coin. Understanding bottom up vs top down isn't just some academic exercise for MBA students. It’s actually the difference between a company that breathes and one that just... functions.

Most people think it’s a binary choice. It isn't.

The heavy hand of top down management

Top down is the old guard. Think Henry Ford. Think the military. It’s a hierarchy where the "brain" is at the top and the "hands" are at the bottom. The core idea here is centralized authority. Decisions are made by a small group of executives who have the "big picture" view, and those decisions are then pushed down to the rest of the organization to execute.

It works. Honestly, it’s why the pyramids got built and why global logistics chains don't collapse tomorrow. When you need massive, coordinated action toward a single, unchanging goal, you need a general. Apple under Steve Jobs was famously top down. Jobs had a vision for what a phone should be, and he didn't ask the assembly line for their opinion on the bezel width. He told them.

But there’s a cost. If the person at the top is wrong, the whole ship hits the iceberg at full speed. There’s no "wait, let’s check the radar" from the lower decks because the lower decks aren't paid to think. They’re paid to row. This creates a massive bottleneck. Innovation dies because it has to travel through seven layers of management before someone with a budget says "yes."

When the ground starts moving: the bottom up revolution

Now, flip that pyramid over. Bottom up is about emergence. It’s the idea that the people closest to the work—the developers, the sales reps, the baristas—actually know what’s going on better than the C-suite does. Instead of a command, you have a culture.

Take a look at how Toyota revolutionized manufacturing with the Total Quality Management (TQM) approach. They gave every single worker on the line the power to pull the "Andon cord." If a worker saw a defect, they pulled the cord and the entire assembly line stopped. That’s bottom up. The person at the bottom of the "hierarchy" had the authority to halt a multi-million dollar operation because they saw a problem the manager missed.

It’s messy, though.

If you go full bottom up without any structure, you get chaos. You get "death by committee." You get 500 people all trying to steer the car in different directions. It’s why many startups struggle as they scale; the "we’re all in this together" vibe works for five people in a garage, but it’s a nightmare for five hundred people in a skyscraper.

The technical divide in data and software

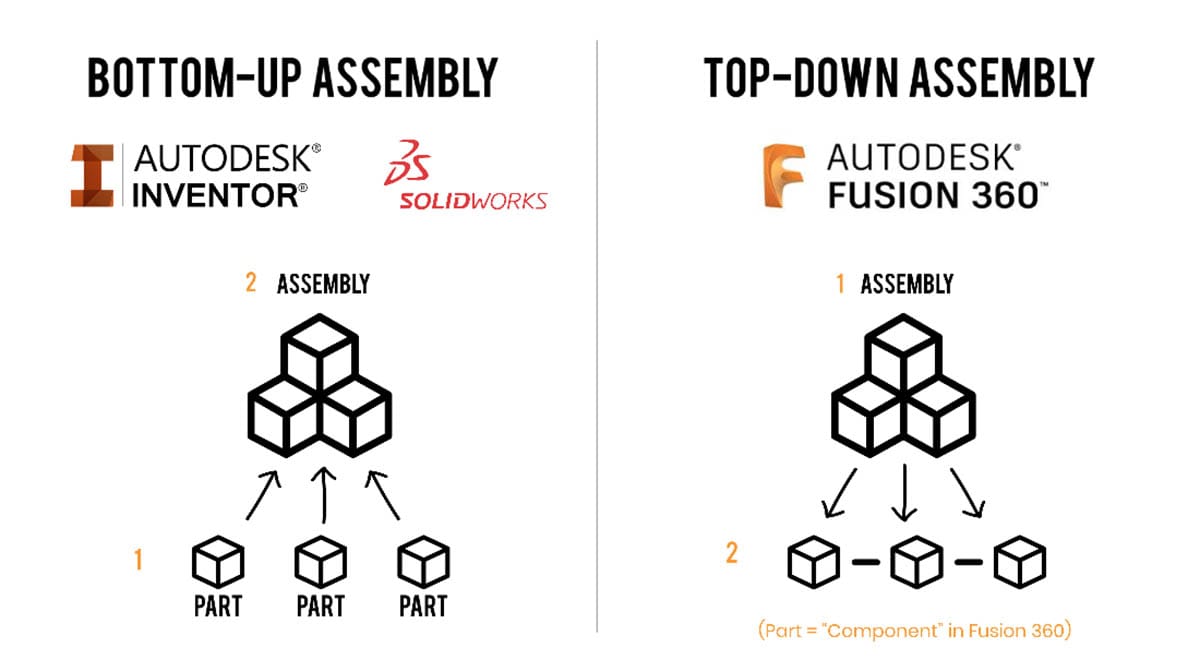

In the world of technology, bottom up vs top down takes on a different flavor. If you’re building a database, a top down approach means you design the entire schema first. You decide exactly what every table looks like before a single piece of data enters the system. It’s rigid, but it’s clean.

Bottom up data processing—think NoSQL or data lakes—is different. You just dump the data in. You figure out the structure later. You let the patterns emerge from the noise.

Software development often hits this wall too. A top down design starts with a massive architecture document. Every interface is defined. Then the coders start. The risk? You spend six months building a "perfect" system that doesn't actually solve the user's problem. Bottom up coding starts with a "Minimum Viable Product." You build a tiny, ugly version of a feature, see if people use it, and then build the rest of the house around it.

Why the "middle" is usually a trap

Companies try to "blend" these, but they usually just end up with the worst of both worlds. They call it "Matrix Management." You have a boss for your function and a boss for your project. Suddenly, you’re spending 40 hours a week in meetings trying to reconcile the top down goals of the company with the bottom up needs of your team.

The real experts—people like Reid Hoffman or the late Andy Grove—didn't try to balance them equally. They used them like tools. Grove, the former CEO of Intel, pushed for "knowledge power" over "position power." He wanted the person who knew the most about a technical problem to lead the meeting, regardless of their title. But once a decision was made? Everyone had to "disagree and commit." That’s a top down enforcement of a bottom up process.

Real world stakes: The NASA example

We can look at the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster for a grim lesson in what happens when these two styles clash. The engineers at Morton Thiokol—the "bottom" of the chain—knew the O-rings might fail in cold weather. They had the data. They tried to push that information up.

But NASA’s management was operating in a strict top down, "we have a schedule to keep" mode. They prioritized the top down goal (launching on time) over the bottom up reality (the hardware is freezing). The hierarchy muffled the experts. This is the ultimate danger of top down systems: they create "information silos" where bad news is filtered out before it reaches the top because no one wants to be the messenger who gets shot.

Practical ways to decide which one you need

So, how do you actually apply this? It depends on the stakes and the speed.

If you’re in a crisis, you go top down. If the building is on fire, you don't want a brainstorming session. You want someone to point at the exit and yell "Go!" High-stakes, fast-paced environments like ER rooms or cockpit decks rely on clear, top down protocols.

If you’re in innovation mode, you go bottom up. If you’re trying to find a new market or solve a creative problem, you need "psychological safety." You need the quietest person in the room to feel comfortable saying your idea is stupid.

💡 You might also like: www frysfood com feedback: What Most People Get Wrong

Breaking the cycle of "Initiative Fatigue"

Most employees hate "top down" because of what I call "The CEO's Summer Reading List." The CEO reads a book on a plane, comes back Monday, and announces a "new initiative" that changes everyone’s workflow. This is top down at its worst. It’s disconnected from the day-to-day reality of the staff.

To fix this, you have to implement "feedback loops." A feedback loop is just a fancy way of saying "listening." If you’re going to set a top down goal (e.g., "We will increase revenue by 20%"), you have to let the teams decide the bottom up how (e.g., "We think the best way to do that is by fixing the checkout page, not by running more ads").

Actionable insights for the modern leader

Stop trying to be one or the other. You’re a conductor, not just a boss.

- Audit your meetings. Are you talking 80% of the time? That’s top down. If you want bottom up results, you need to shut up and ask "What’s the biggest thing slowing you down right now?"

- Define the "What," not the "How." Top down is for setting the destination. "We are going to Mars." Bottom up is for the navigation. Let the experts decide the fuel mix.

- Kill the messenger reward. If someone brings you bad news from the "bottom," thank them. If you punish them, you’ve just ensured you’ll never see a problem coming until it’s too late.

- Use "Commander’s Intent." This is a military concept. You don't give a 50-page order. You say, "The goal is to take that hill so the supply trucks can pass." If the situation changes, the soldiers on the ground know the goal and can adapt their tactics without waiting for a new order.

The tension between bottom up vs top down is never going away. It’s the friction that makes organizations move. If you have too much top down, you’re brittle. If you have too much bottom up, you’re a puddle. The trick is knowing when to grab the wheel and when to let the car drive itself.

Start by looking at your current project. Is it stalled because no one is leading, or because no one is listening? That answer tells you exactly which way you need to shift.