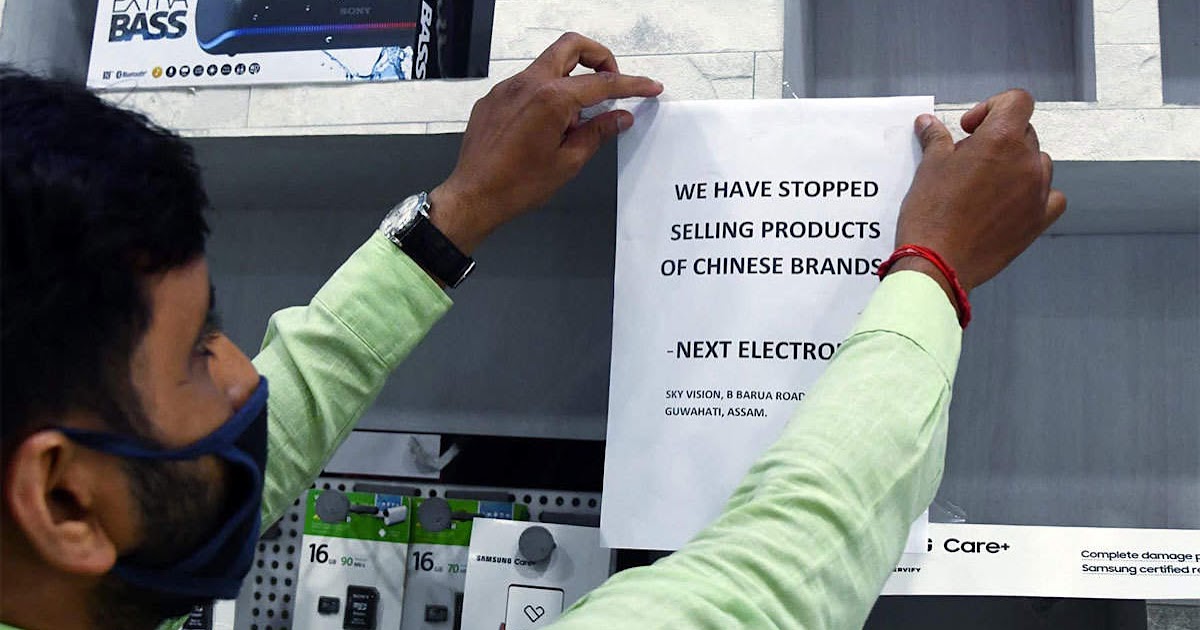

You’ve probably seen the word trending on your feed a dozen times this week. Someone is mad at a coffee chain. Another group is deleting an app. It feels like a modern reflex, but if we’re asking boycott what does it mean in the grand scheme of history, it’s a lot more than just a hashtag or a temporary dip in a stock price. It is, at its core, an organized refusal to buy, use, or participate in something as a way of protest. It’s a collective "no."

But honestly, most people get the mechanics wrong. They think it's just about staying away from a store for a week. It isn't.

The word itself actually comes from a person’s name. Captain Charles Boycott was an Irish land agent in the 19th century. When he tried to evict struggling tenants, the local community didn’t attack him with pitchforks. Instead, they just... stopped. They wouldn't work his fields. The postman wouldn't deliver his mail. The local shops wouldn't sell him food. He became a social ghost. That’s the purest form of the concept: total economic and social isolation.

Today, things are messier. We live in a globalized economy where boycotting a single brand often means you’re accidentally supporting five of its subsidiaries without knowing it. It’s complicated.

Why We Refuse to Buy: The Psychology of the "No"

Most people engage in a boycott because they want to feel like their wallet has a voice. It’s about agency. When you feel like you can't change a law or stop a war, you can at least control where your twenty dollars goes.

Brayden King, a professor at Northwestern University, has spent years studying this. His research suggests something pretty counterintuitive: most boycotts don't actually tank a company's sales in the long run. Corporations are massive. They have deep pockets and diverse revenue streams. So, if the sales don't always drop, why do people keep doing it? Because the real damage is to the brand reputation.

A company’s image is its most fragile asset. When a boycott stays in the news cycle, it forces the CEO to spend time answering questions about ethics rather than growth. It makes investors nervous. Not because the company is going bankrupt, but because the "vibe" has shifted.

The Difference Between a Boycott and a Buycott

Sometimes, the most effective way to protest is the opposite of a boycott. Enter the "buycott." This is when consumers actively flock to a brand specifically because it aligns with their values. Think about the surge in support for local bookstores when people got tired of big-tech monopolies. It’s a positive reinforcement loop.

While a boycott is a "stop doing that," a buycott is a "keep doing this."

Often, these two happen simultaneously. When people walked away from traditional taxis to support ride-sharing apps, they were boycotting a stagnant industry. Later, when those same apps faced scandals, users fled back to competitors. It’s a constant, shifting tide of consumer sentiment.

When Does a Boycott Actually Work?

If you want to know boycott what does it mean for a business's bottom line, you have to look at the success stories. And they are rarer than you think.

Take the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955. This is the gold standard. It lasted 381 days. Think about that for a second. Over a year of walking, carpooling, and organizing. It wasn't a "don't buy this for a weekend" thing. It was a disciplined, localized, and sustained economic strike that crippled the city's transit revenue. It had a clear goal: desegregation.

Contrast that with modern "cancel culture" boycotts. Most of these fizzle out within 72 hours. Why? Because there’s no infrastructure. There’s no "what happens next." To work, a boycott needs three things:

- A Clear, Achievable Goal: "Stop being a bad company" is too vague. "Remove this specific chemical from your product" or "Change this specific labor policy" works better.

- No Easy Alternatives: If there’s nowhere else to buy bread, the boycott dies. If there are ten other bakeries on the same block, the business is in trouble.

- Media Oxygen: If no one is talking about it, the company can just wait it out.

There was a famous case with Nestlé in the 1970s and 80s regarding their marketing of baby formula in developing nations. That boycott lasted years and led to the World Health Assembly adopting a strict international code. It worked because it was relentless and global. It wasn't just a trend; it was a movement.

The Role of Social Media: Helpful or Hurting?

Social media has made it incredibly easy to start a protest. You post a video, it goes viral, and suddenly a million people are mad at a brand. But this ease is a double-edged sword. It creates "slacktivism."

You might click "like" on a boycott post, but do you actually change your shopping habits when you’re tired and just need a quick snack at 11 PM? Often, the answer is no. This creates a gap between "online noise" and "offline action."

Companies know this. They hire data firms to track if the outrage is actually hitting the cash register. If the Twitter (X) mentions are high but the sales stay flat, the company will usually just release a bland PR statement and wait for the next news cycle to take over.

The Ethics of Disengaging

We also have to talk about the collateral damage. This is the part people hate to acknowledge. When a massive boycott actually succeeds in hurting a company, who loses their job first? It’s rarely the CEO with the golden parachute. It’s the warehouse workers, the delivery drivers, and the retail staff.

In 2014, workers at the Market Basket grocery chain actually boycotted for their CEO, Arthur T. Demoulas, after he was fired by the board. It was a "reverse boycott." Customers stayed away to support the employees. This is a rare example where the workers and the consumers were on the same side. It worked. The CEO was reinstated.

This shows that boycott what does it mean is ultimately about power dynamics. It’s a tool used by the many to influence the few. But like any tool, it can be blunt and messy.

✨ Don't miss: The Jack in the Box Rises: Why This Fast Food Comeback Is Actually Working

Misconceptions You Probably Believe

- "Boycotts are always left-wing." Nope. Not even close. Some of the most organized boycotts in recent years have come from conservative groups targeting brands for "going woke." The political spectrum doesn't own the concept. Everyone uses it.

- "Stock prices are the best way to measure success." Actually, stock prices often bounce back quickly. The better metric is "Customer Acquisition Cost." If a boycott makes it harder or more expensive for a company to get new customers, that’s where the real pain is.

- "One person doesn't matter." While one person's $5 doesn't change a billion-dollar company, the perception of a growing crowd does. Companies are terrified of trends. They aren't afraid of you; they are afraid of the thousands of you.

How to Effectively Participate in a Boycott

If you’re serious about making an impact, you can't just stop buying a product. You have to be strategic. Honestly, most people just get loud on the internet and then forget about it two weeks later. If you want to actually move the needle, you’ve gotta do more.

First, do your homework. Is the company you're mad at actually responsible, or are they just a small part of a much larger parent corporation? If you boycott a brand but keep buying from its parent company, you're basically just moving money from one pocket to another. Check the corporate structure. Use sites like "Good On You" for fashion or "OpenSecrets" to see where a company’s political donations go.

Second, communicate why. A company seeing a 2% dip in sales might think it’s just a bad quarter or a shift in the weather. They need to know exactly why they are losing money. Write an email. Tag them. Send a physical letter—those actually get read because they’re so rare now. Tell them: "I am a long-time customer, and I am stopping my purchases until [X] changes."

Third, find a replacement. A boycott only lasts as long as your willpower. If you don't find a better alternative to the product you're ditching, you’ll eventually crawl back out of convenience. Find a local or ethical competitor and make them your new go-to.

Lastly, set a timeline. Is this a "forever" ban, or are you waiting for a specific policy change? Successful movements have "off-ramps." If a company meets your demands and you keep boycotting them, you’ve removed the incentive for other companies to ever listen to protesters in the future. Reward the change you asked for.

At the end of the day, understanding boycott what does it mean is about recognizing that your money is a vote. You cast it every single day. Whether it's at a gas station, a grocery store, or an app store, you are constantly choosing which version of the future you want to fund. It’s a slow process, and it’s often frustrating, but it’s one of the few direct levers the average person has in a massive, corporate-driven world.

Think of it as a muscle. If you use it randomly and without focus, you’ll just get tired. But if you train it and use it with others, you can actually move things that seemed unmovable.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your subscriptions: Check if you are monthly funding a company whose values you actually hate. It’s easy to let those $9.99 charges slide.

- Identify the "Parent": Before your next big purchase, search "[Brand Name] parent company." You might be surprised who actually owns the "independent" brand you love.

- Start small: Instead of boycotting everything at once, pick one specific industry (like fast fashion or big tech) and find one ethical alternative this month.

- Use your voice, not just your silence: If you stop using a service, tell the company why on your way out. Use their "cancelation reason" box to be specific.