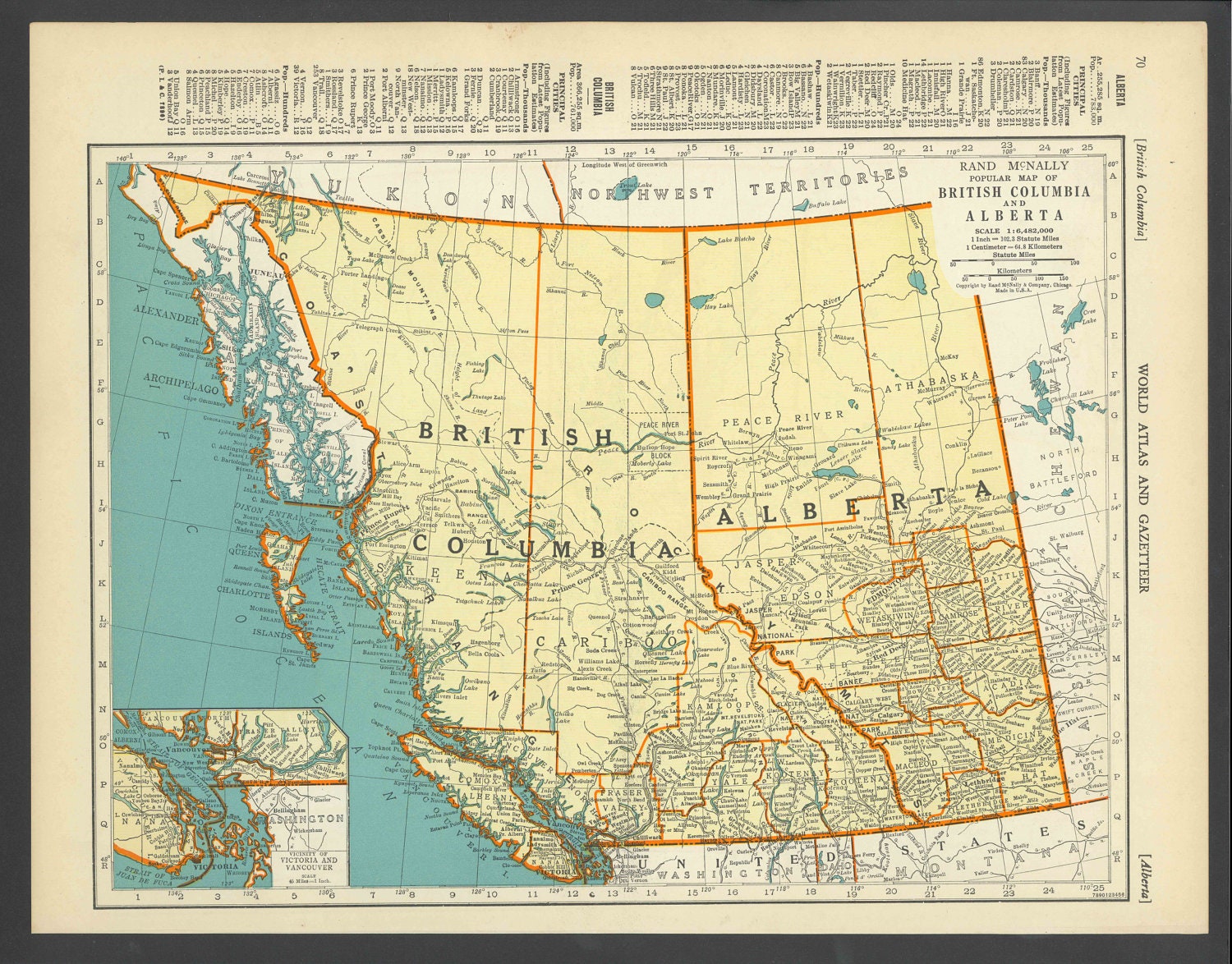

You’ve probably seen the classic British Columbia and Alberta map a thousand times. It’s that jagged, diagonal line that looks like a staircase cutting through the heart of Western Canada. Most people just see it as a border between the mountains and the prairies. But honestly, if you look closer, that line tells a story of absolute chaos, 1913 survey teams fighting off grizzly bears, and a geographical split that doesn't actually follow the mountains the way we assume it does.

Geography is weird.

For starters, that border is roughly 1,842 kilometers long. That makes it the longest provincial boundary in Canada. But it isn't just one straight line. It’s actually two completely different types of borders mashed together. The top half is a "man-made" straight line following the 120th meridian. The bottom half? That’s where things get wild. It follows the Continental Divide, the literal spine of the Rocky Mountains.

The Great Divide and the "Staircase"

When you’re looking at a British Columbia and Alberta map, the southern portion follows the height of land. Basically, if a raindrop falls on the Alberta side, it eventually ends up in the Atlantic or Arctic Oceans. If it falls a few inches to the west in BC, it’s heading for the Pacific.

This isn't just trivia.

Back in 1913, guys like Arthur Wheeler and Richard Cautley spent years hauling heavy equipment up peaks like Mount Assiniboine and through the Kicking Horse Pass just to figure out where one province ended and the other began. They had to deal with massive snowfalls in July and rivers that changed course overnight. They even had a system where they labeled mountain passes with letters. Kicking Horse Pass was "Pass A." Yellowhead was "Pass S."

It took them until the 1920s to finish.

And get this—because they were following the "height of land," the border doesn't always feel "right" when you're driving it. You can be deep in the mountains and technically be in Alberta, or you can be in the relatively flat Peace River Country and be firmly in British Columbia.

Why the 120th Meridian Matters

The northern half of the map is a total 180-degree turn. Once you hit the intersection of the Rockies and the 120th meridian, the border just gives up on the mountains and shoots straight north to the 60th parallel.

📖 Related: Notes on the Old Cross on Canna: What Most People Get Wrong

This creates a weird cultural pocket.

Places like Dawson Creek and Fort St. John in BC feel way more like Alberta than they do like Vancouver. They have the same rolling prairies, the same oil and gas economy, and even the same "flat" horizon. If you didn't see the "Welcome to British Columbia" sign on Highway 43, you’d swear you were still outside of Grande Prairie.

Navigating the Three Main Veins

If you're planning a road trip across a British Columbia and Alberta map in 2026, you're basically choosing between three main "veins" that pulse through the Rockies. Each has a completely different vibe.

1. The Trans-Canada (Highway 1)

This is the big one. It takes you through Banff, Yoho, and Glacier National Park. It’s where you’ll find Roger’s Pass, which sits at an elevation of 1,327 meters. It’s stunning, but it’s also the busiest. If you're driving an EV, 2026 is a great year for this route because the charging infrastructure through the mountains has finally caught up to the demand.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Royal Portuguese Reading Room in Rio is Actually Worth the Hype

2. The Yellowhead (Highway 16)

This is the "chill" route. It crosses the border at Yellowhead Pass near Mount Robson, the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies at 3,954 meters. The pass itself is actually surprisingly low and flat—only 1,066 meters. It’s the easiest drive, especially in winter, because it doesn't have the terrifying steep grades you find further south.

3. The Crowsnest (Highway 3)

This is the rugged, old-school choice. It crosses at Crowsnest Pass (elevation 1,358 meters). It takes you through historic mining towns like Fernie and Sparwood. You’ll pass the Frank Slide, where half a mountain fell over a hundred years ago. It’s narrower, twistier, and honestly, way more interesting if you aren't in a rush.

The "Hidden" Geography Most People Miss

Most maps don't emphasize the Rocky Mountain Trench.

It’s this massive geological valley that runs parallel to the Rockies on the BC side. When you cross the border from Alberta into BC at Kootenay National Park, you eventually drop down into this trench. It’s so big you can see it from space. It separates the "true" Rockies from the Columbia Mountains (the Purcells, Selkirks, and Monashees).

A lot of tourists think they're still in the Rockies when they’re skiing at Revelstoke or Kicking Horse, but technically? They’re in the Columbia system.

What You Need to Know for 2026

Travel trends for 2026 show a massive shift toward "Alps-style" year-round mountain escapes. People aren't just going for ski season anymore. They're chasing the "Altitude Shift"—finding stillness in the high alpine during the shoulder seasons.

- Connectivity: Cell service in the "dead zones" between Golden and Revelstoke is getting better, but the map still has plenty of spots where your GPS will go dark. Download offline maps. Seriously.

- National Park Permits: If your map takes you through Banff or Jasper, you need a pass. But in 2026, they've tightened up the "crowd management" tools. You might need to reserve your entry for specific popular trailheads months in advance.

- The "Anywhere but the US" Factor: More Canadians are choosing to stay domestic this year. Expect the highways between Calgary and Vancouver to be busier than usual.

Actionable Next Steps

If you're looking at a British Columbia and Alberta map and trying to plan a move or a massive trip, don't just look at the red lines (highways). Look at the green spaces.

🔗 Read more: Andean cock of the rock adaptations: Why this bird looks and acts so weird

- Check the Fire Maps: In 2026, seasonal wildfire smoke is a reality. Before you book a "scenic" mountain hotel, check the historical smoke patterns for that specific valley.

- Verify Your Time Zones: Most of BC is on Pacific Time, and Alberta is on Mountain Time. But—and this is a big "but"—places like Creston and the Peace River region in BC often ignore Daylight Savings or stay on Mountain Time to match their Alberta neighbors.

- Get a Physical Map: It sounds "retro," but the 2026 Edition MapArt folded maps are still the gold standard for backroads. Digital maps often miss forestry roads that can be lifesavers (or dangerous traps) if the main highway gets blocked by a mudslide or accident.

The border between these two provinces isn't just a political line; it’s a massive, physical wall that shaped how Canada was built. Whether you're crossing it at the Crowsnest or the Peace River, you’re moving between two completely different worlds.