Robert Altman was never one for the status quo. In 1976, while the rest of the United States was busy patting itself on the back for the Bicentennial, Altman released Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson. It didn't go well. People expected a sweeping Western epic or a heroic tribute to a frontier icon. Instead, they got a messy, cynical, and deeply funny deconstruction of how America invents its own legends. Honestly, it’s a miracle it got made at all.

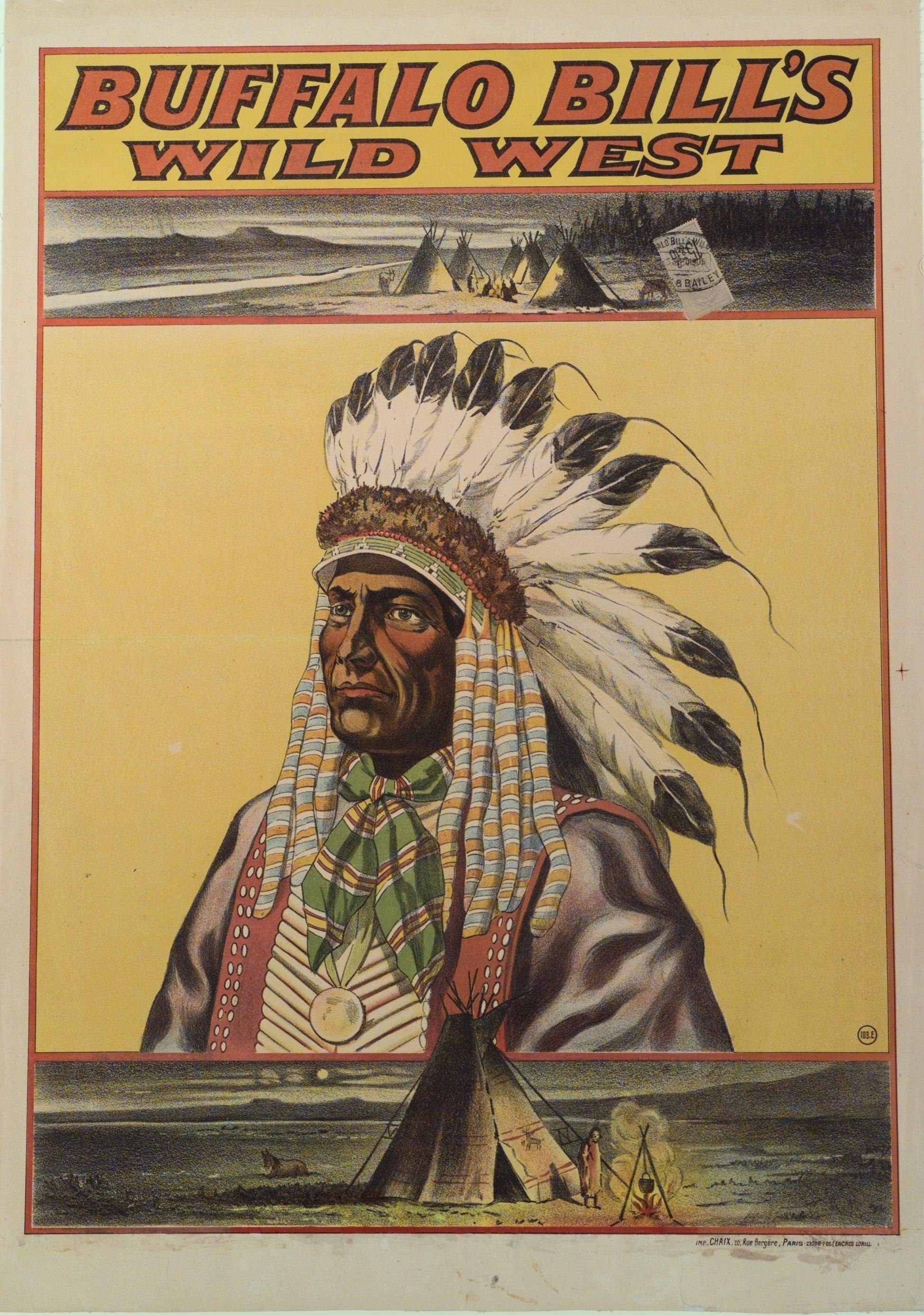

The film stars Paul Newman as William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody. But this isn't the Buffalo Bill from your middle school history textbook. Newman plays him as a man trapped by his own wig. He's a performer who has forgotten where the show ends and reality begins. It’s a movie about the "Wild West" that never actually goes to the West; the entire thing takes place within the confines of Cody’s circus-like encampment.

The Myth of the Self-Made Hero

Altman’s target isn't really the historical Cody. It’s the industry of celebrity. In Buffalo Bill and the Indians, Cody is surrounded by enablers—his producer Nate Salsbury (Joel Grey) and his nephew Ed Goodman (Harvey Keitel). They aren't building a country; they're building a brand. This was 1976, but it feels like it could have been written yesterday about any viral influencer or politician.

The plot, if you can call it that, kicks off when Cody hires the legendary Lakota leader Sitting Bull (Frank Kaquitts) to join the show. Cody expects a defeated warrior who will play-act his surrender for the crowds. He gets the opposite. Sitting Bull doesn't speak through the film; he uses a translator, William Halsey (Will Sampson), and he refuses to play the part of the "savage."

This creates a massive ego bruise for Cody. He’s a man who believes his own press releases. Newman is brilliant here because he plays Cody with a sort of frantic insecurity. You see him constantly adjusting his hairpieces and practicing his poses. He’s a hollow man. He’s basically a 19th-century version of a reality TV star who is terrified that the audience will see behind the curtain.

Why 1970s Audiences Hated It

You have to understand the context. In 1976, the vibe in America was "The Bicentennial." It was all about red, white, and blue celebrations. Then comes Robert Altman, fresh off the success of Nashville, throwing a cold bucket of water on the party. He’s essentially saying that the foundation of the American West was a series of staged lies and PR stunts.

Critics weren't kind. Some felt the movie was too smug. Others felt it was repetitive. The pacing is definitely "Altmanesque," meaning it’s loose, talky, and filled with overlapping dialogue. If you’re looking for a shootout, you’re in the wrong place. The only "action" is choreographed for the grandstand.

Interestingly, the film won the Golden Bear at the 26th Berlin International Film Festival, but back home in the States, it tanked at the box office. People weren't ready to see Paul Newman, the ultimate golden boy, playing a fraud. It felt like an attack on American identity itself.

Sitting Bull vs. The Great Showman

The heart of Buffalo Bill and the Indians is the silent standoff between Cody and Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull represents the truth—ugly, quiet, and unyielding. Cody represents the legend—loud, fake, and constantly needing validation.

There is a specific scene where Sitting Bull asks for a favor. He wants Cody to help him tell the story of a dream he had. Cody, of course, assumes it's about a battle or something "marketable." When the dream turns out to be a quiet, spiritual request, Cody is baffled. He literally cannot process information that doesn't fit into a three-act structure with a hero and a villain.

- The Cast: It’s a powerhouse. Beyond Newman and Keitel, you’ve got Geraldine Chaplin as Annie Oakley. She’s fantastic as a woman who is both a victim of the myth and a willing participant in it.

- The Script: Based loosely on the play Indians by Arthur Kopit, the screenplay by Altman and Alan Rudolph is incredibly dense. You’ll catch things on a third viewing that you missed on the first.

- The Cinematography: Shot by Paul Lohmann, the film has a hazy, almost dreamlike quality. It feels like you’re looking at an old, sepia-toned photograph that is slowly starting to rot.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Film

A common misconception is that the movie is "anti-American." That’s a lazy take. It’s actually a movie about how much we love stories. We love them so much that we prefer a good lie over a boring truth. Cody isn't a "villain" in the traditional sense; he's just a guy who realized that being a hero pays better than being a scout.

Altman captures the moment where history became "show business." Think about it. The real Buffalo Bill was one of the most famous people on the planet. He brought the "West" to London, Paris, and New York. But it was a version of the West that never existed. It was filtered through costumes and blank cartridges.

Another thing people miss is the humor. It’s a very funny movie, provided you like dry, cynical wit. The way the staff bickers over the logistics of "authenticity" while completely ignoring the actual Indigenous people standing right in front of them is peak satire.

The Ending Nobody Likes (But Everyone Needs)

The final sequence of Buffalo Bill and the Indians is haunting. Sitting Bull is dead—not in battle, but in a way that feels mundane and tragic. Cody, meanwhile, has to keep the show going. He has a vision—a literal hallucination—of Sitting Bull. He tries to "defeat" the ghost of the man in a staged duel.

It’s pathetic. It’s Cody desperately trying to reclaim the narrative. He wins the "fight" in the show, but the look on Newman's face tells you he knows he's lost the war for his soul. He is a prisoner of his own creation.

The movie ends with a long, slow zoom-out. It leaves you feeling a bit empty, which was exactly the point. Altman didn't want to give you a satisfying conclusion because the myth of the West doesn't have one. It just keeps being repackaged and sold to the next generation.

How to Watch It Today

If you’re going to sit down with Buffalo Bill and the Indians, you need to change your mindset. Don't look at it as a Western. Look at it as a workplace comedy set in a propaganda factory.

💡 You might also like: Jesse Eisenberg Recent Movies: Why the Social Network Star is Suddenly Everywhere Again

- Pay attention to the background. In typical Altman fashion, there are things happening in the corners of the frame that are often more important than the main dialogue.

- Listen to the silence. Frank Kaquitts’ performance as Sitting Bull is one of the most powerful "silent" roles in cinema. His presence dominates the screen without him saying a single word.

- Watch the hair. Seriously. Paul Newman’s wigs in this movie are a character of their own. They represent the artificial layers Cody has built around himself.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Viewer

To truly appreciate this film, you have to look at how we consume "history" today. We are still doing exactly what Buffalo Bill did. We take complex, messy human events and we sand them down until they are smooth enough to fit into a social media post or a blockbuster movie.

- Question the Narrative: Whenever you see a "biopic" or a "true story," ask yourself what is being left out to make the "hero" look better.

- Study the Era: Read about the actual 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. It’s where Cody’s show reached its peak and where the "Frontier Thesis" was first presented. The movie captures that atmosphere of transition perfectly.

- Explore Altman's Trilogy: To get the full picture, watch this alongside MASH and McCabe & Mrs. Miller. These three films represent Altman’s "de-mythologizing" of American institutions: the military, the entrepreneur, and the legend.

The film is a reminder that the truth is usually quiet, while the lie is always wearing a costume and charging admission. It’s a tough pill to swallow, especially during a Bicentennial, but it’s a necessary one. Altman wasn't trying to destroy the American spirit; he was trying to wake it up. Whether he succeeded is still up for debate, but the film remains a sharp, stinging piece of work that hasn't lost its edge in fifty years.