Standard pregnancy math is weird. If you walk into an OB-GYN office today, the first thing they’ll ask is the date of your last menstrual period (LMP). They plug that date into a wheel or a software program, and boom—you have a due date. But here’s the kicker: that math assumes every single woman has a perfect 28-day cycle and ovulates exactly on day 14.

Honestly? Most people don't.

Some women ovulate on day 10. Others don't release an egg until day 22. If you happen to be a "late ovulator," using your period to track your pregnancy will actually make you appear further along than you really are. This leads to unnecessary stress about "slow growth" or premature induction talks later on. That’s why you should calculate due date based on ovulation if you actually know when it happened. It’s just more precise. It's the difference between a guess and a data-backed estimate.

The Flaw in Naegele’s Rule

Most doctors use Naegele’s Rule. It’s an old-school formula from the early 19th century. You take the first day of your LMP, add seven days, and subtract three months. It’s simple. It’s fast. It’s also frequently wrong.

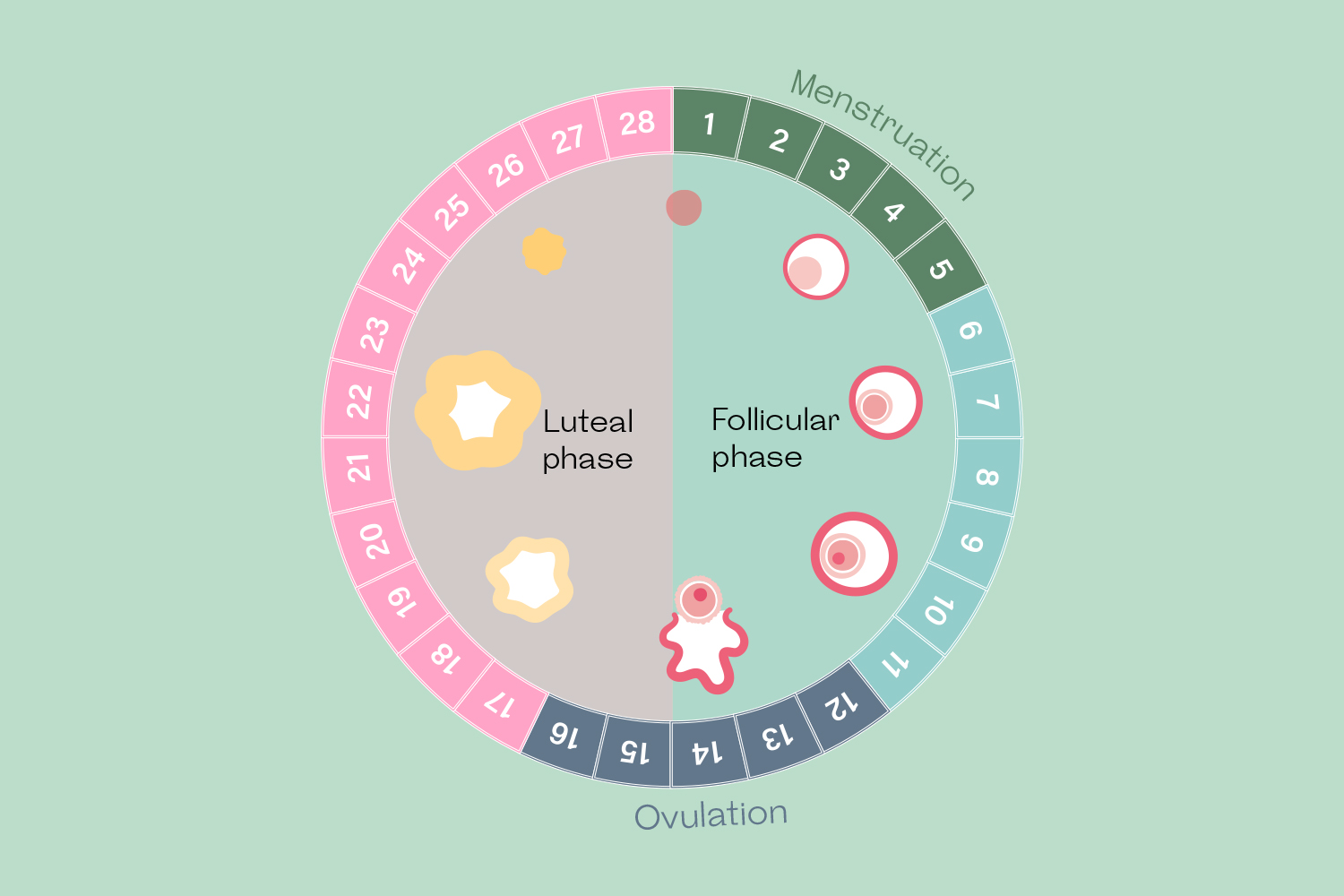

The rule relies on the "average" cycle. But a study published in Human Reproduction found that only about 13% of women actually have a 28-day cycle. If your cycle is 35 days long, Naegele’s Rule will be off by a full week. When you calculate due date based on ovulation, you bypass the follicular phase—that unpredictable time between your period and the moment the egg is released.

Conception doesn't happen on the day you have a period. It happens when the sperm meets the egg. Period.

How to Do the Math Yourself

If you were tracking your basal body temperature (BBT), using ovulation predictor kits (OPKs), or monitoring cervical mucus, you likely have a very good idea of your peak fertility day. Once you have that date, the calculation is actually pretty straightforward.

You aren't pregnant for nine months. You're pregnant for 266 days from the moment of fertilization.

To find your "real" due date, just add 266 days to your ovulation date. Alternatively, if you want to use the standard 40-week (280-day) gestational model that doctors prefer, you just work backward. Since "medical" pregnancy age includes the two weeks before you even conceived, you take your ovulation date and subtract 14 days. That result is your "adjusted LMP." From there, you can use any standard pregnancy calculator or add 280 days.

Let's say you ovulated on May 20th.

Subtracting 14 days gives you an adjusted LMP of May 6th.

Your due date would be February 10th.

It feels like time travel. It basically is.

Why This Accuracy Matters for Medical Decisions

Precision isn't just for your nursery planning. It has massive clinical implications.

Take "post-term" pregnancies, for instance. Most practitioners get nervous once a woman hits 41 or 42 weeks. If your due date is based on an LMP from a long cycle, you might be told you're 42 weeks pregnant when, based on your ovulation, you’re actually only 41 weeks. This leads to inductions that wouldn't have otherwise happened.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), an early ultrasound (before 14 weeks) is the most reliable way to date a pregnancy. But even then, there is a margin of error. If you have clear data from your ovulation tracking, show it to your provider. Many midwives and progressive doctors will take your "ovulation-adjusted" date seriously, especially if it aligns with the early crown-rump length (CRL) measurements on a scan.

The Luteal Phase Factor

Every woman has a different follicular phase (the time it takes to grow an egg), but the luteal phase (the time after ovulation) is usually pretty consistent, typically lasting 12 to 16 days. If you have a short luteal phase, your period might arrive sooner than expected, but your pregnancy math remains the same.

Tracking this isn't just about the due date. It’s about understanding your body's rhythm.

Common Misconceptions About Conception Dates

People often confuse the "date of intercourse" with the "date of ovulation." This is a huge mistake. Sperm can live inside the female reproductive tract for up to five days. You could have sex on a Monday and not ovulate until Friday. You didn't conceive on Monday. You conceived on Friday.

If you're trying to calculate due date based on ovulation, don't use the day you "did the deed." Use the day the egg was actually released. If you aren't sure which day that was, look for the day your BBT spiked or the day after your first positive OPK.

👉 See also: Over the counter niacinamide: What nobody tells you about that $10 bottle

When the Ultrasound Disagrees

It happens. You've tracked everything. You know your body. You've got the data. Then you go in for your 8-week scan, and the technician says, "You're measuring five days behind."

Don't panic.

Early growth can be slightly variable. However, if the discrepancy is more than seven days, most doctors will "re-date" you based on the ultrasound. This is because, in the first trimester, embryos grow at a very predictable rate. If your ovulation math says you are 9 weeks but the scan says 7 weeks, it’s possible the egg took a bit longer to implant.

Implantation usually happens 6 to 12 days after ovulation. This tiny window of time is the final variable that math can't always account for.

Summary of Actionable Steps

- Check your data. Look back at your tracking app or paper charts. Pinpoint the day of your LH surge or your BBT shift.

- Do the 266-day add. Add 266 days to that specific date to find your biological due date.

- Establish your "Adjusted LMP." Subtract 14 days from your ovulation date. Use this date when filling out forms at the doctor's office—it will make their standard wheels align with your actual biological timeline.

- Compare with your first scan. If your ovulation-based date is within 3–5 days of the ultrasound date, you’re on the right track.

- Advocate for yourself. If you have long cycles, tell your OB-GYN immediately. Explain that your LMP will give an inaccurate due date because you ovulate later than day 14.

The goal is to avoid being labeled "high risk" or "overdue" simply because of a math error rooted in the 1800s. Your body doesn't run on a standard calendar. It runs on its own internal clock. Use your data to make sure your medical care reflects that reality.