You just got a raise. Congrats. You're feeling great until you look at that first paycheck and realize the state of California took a massive bite out of your celebration. It feels like you’re being punished for succeeding. Honestly, the way people talk about California marginal tax rates makes it sound like a giant vacuum cleaner for your bank account, but there is a lot of nuance that gets lost in the shouting matches on social media.

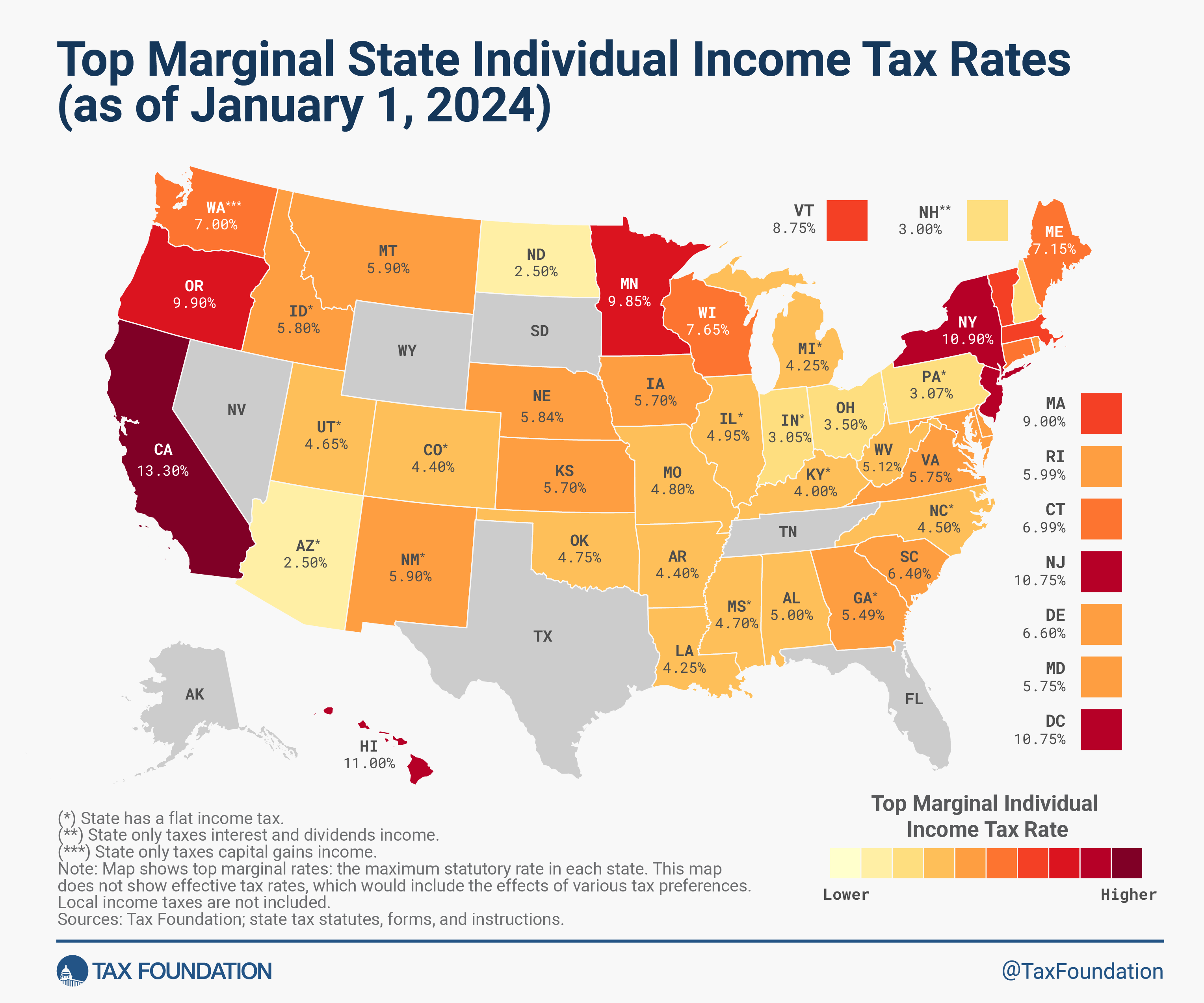

If you live here, you know the Golden State is expensive. We have the highest top-tier tax rate in the country. That is a fact. But how that actually hits your wallet depends entirely on the "marginal" part of the equation, a concept that even high-earners consistently misunderstand.

Most people think that if they move into a higher tax bracket, all their money is suddenly taxed at that new, higher rate. That is absolutely wrong. It’s a ladder. You pay the lower rates on the first rungs of your income, and only the "new" dollars you earn get hit with the higher percentage.

The Mental Math of California Marginal Tax Rates

Let's get real about the numbers. California uses a progressive tax system with ten different brackets. It starts at a tiny 1% and climbs all the way up to 13.3%. That top number includes the 1% Mental Health Services Act tax that kicks in once you cross the $1 million threshold.

Think about your income like a series of buckets. The first bucket is small—around $10,000 for single filers. No matter how much you make, that first $10,000 is taxed at 1%. You could be a billionaire or a barista; that specific slice of income is treated the same. As you earn more, you start filling the 2% bucket, then the 4%, and so on.

Why does this matter? Because when someone says "I'm in the 9.3% bracket," they aren't actually paying 9.3% of their total income to Sacramento. Their effective tax rate—the actual percentage of their total paycheck that goes to the state—is much lower.

For a single person making $100,000, the top marginal rate is 9.3%. But because of those lower buckets, they aren't paying $9,300. They’re likely paying closer to $6,000 or $7,000 before deductions. It’s a huge distinction.

Why the "Millionaire Tax" Isn't Just for Millionaires

The 1% Mental Health Services Act tax is a famous piece of California legislation. Passed as Proposition 63 back in 2004, it tacks an extra 1% onto any taxable income over $1 million. This is how California gets to that eye-popping 13.3% figure.

But here is where it gets tricky for business owners and people with fluctuating incomes. If you sell a house or a business and have a "one-time" windfall that pushes you over that million-dollar mark, you are hit with that extra 1% on every dollar above the threshold. It doesn't matter if you usually make $80,000 a year. For that specific year, you’re in the elite tier.

The Franchise Tax Board (FTB) is incredibly efficient at tracking this. Unlike the IRS, which sometimes feels like a slow-moving giant, the FTB is known for being nimble and, frankly, a bit aggressive. They track residency and income sources with a level of scrutiny that catches a lot of "tax refugees" off guard when they try to move to Nevada or Texas while still earning California-sourced income.

The Deductions That Actually Move the Needle

You can’t talk about California marginal tax rates without talking about the Standard Deduction and the California Personal Exemption Credit. For the 2024 and 2025 tax years, these numbers adjust for inflation, but they remain the primary way most people lower their taxable base.

- The Standard Deduction for single filers is roughly $5,363.

- The Personal Exemption Credit is around $144.

These might seem like small potatoes compared to federal numbers, but in a progressive system, every dollar you "hide" from the top bracket is a win. If you’re a freelancer or a small business owner, your expenses are your best friend. California generally follows federal rules for business expenses, but there are some "conformity" issues where the state doesn't always agree with the feds on things like depreciation.

Honestly, the biggest mistake people make is not realizing that California tax law is its own beast. Just because something is deductible on your 1040 doesn't mean the FTB will allow it on your Form 540.

Inflation and the "Bracket Creep" Problem

California actually does something decent here: they adjust the tax brackets for inflation every year. This is designed to prevent "bracket creep."

Imagine you get a 5% cost-of-living raise. If the tax brackets stayed the same, that raise might push you into a higher marginal bracket, meaning the state takes a bigger percentage of your income even though your "buying power" hasn't actually increased. By shifting the brackets up slightly each year, the state tries to ensure you only pay higher rates if you are actually getting wealthier in real terms.

👉 See also: ups stock price today: Why Big Investors Are Shaking Things Up

It isn't perfect. Real estate prices and gas costs in San Diego or San Francisco often outpace these adjustments. You feel poorer even if the tax tables say you're doing fine.

The Strategy: Managing Your Marginal Exposure

If you are hovering near the edge of a higher bracket—say you’re a single filer around $68,000 where the jump to 9.3% happens—you have options.

Contributing to a traditional 401(k) or a 403(b) is the most effective "instant" fix. These contributions reduce your California Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). If you put $10,000 into a 401(k), the state acts like you never earned that money. You’ve effectively chopped $10,000 off your highest-taxed "bucket."

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) are a different story. This is a classic California trap. On the federal level, HSA contributions are tax-deductible. In California? Nope. The state treats HSA contributions as taxable income. It’s one of those weird quirks that catches transplants from other states off guard every single April.

Residency: The Nuclear Option

We've all heard the stories of people fleeing to Florida or Austin to escape the California marginal tax rates. It sounds easy. You pack a U-Haul, get a new driver's license, and boom—0% state income tax.

Not so fast.

The FTB uses what they call the "closest connection test." They look at where you registered your cars, where your kids go to school, where you see your dentist, and even where you maintain your gym membership. If you leave but keep a "vacation home" in Tahoe and spend four months a year there, the FTB might decide you never actually left. They will hunt down that income.

The burden of proof is on you, not them. If you’re planning a move to save on taxes, you need a "clean break." Keep a log. Change your voter registration immediately. Don't leave a "paper trail" that leads back to a California residence.

Real-World Impact: The "Working Rich"

The people who get hit hardest by California’s structure aren't necessarily the ultra-wealthy with armies of accountants. It’s the "working rich"—professionals like dual-income lawyers, doctors, or tech leads making $300,000 to $600,000.

At this level, you’re firmly in the 9.3% or 10.3% brackets. You don't have the massive capital gains of a tech founder, so most of your income is "ordinary." You’re paying the high rates on almost every dollar above the median. For these folks, the combination of high state tax and the federal SALT (State and Local Tax) deduction cap of $10,000 feels like a double-tap to the wallet.

Actionable Steps to Lower Your Bill

Since you can't change the laws, you have to play the game better.

First, look at your "tax-exempt" interest. California doesn't tax interest from its own municipal bonds. If you have a brokerage account, holding California-specific muni bonds can provide income that is double-tax-free (both federal and state).

Second, if you’re a business owner, look into the Pass-Through Entity (PTE) Elective Tax. This is a relatively new workaround for the federal $10,000 SALT cap. It allows certain businesses to pay state taxes at the entity level, which then becomes a federal deduction. It’s a complex move that requires a pro, but it can save you thousands in a single year.

Third, audit your "sourced" income. If you do freelance work for a company in New York while sitting in a coffee shop in Santa Monica, California considers that California-sourced income. However, if you travel for work, keep meticulous records. Income earned while physically working in other states might be eligible for a credit (Schedule S) so you aren't taxed twice.

What to Do Next

Don't wait until April to look at this.

- Check your AGI. Pull last year’s return and see exactly where you fell in the brackets. Are you within $5,000 of a lower bracket?

- Max the "state-recognized" accounts. Focus on your 401(k) or 403(b) first since California recognizes these deductions.

- Review your "conformity" errors. If you have an HSA or certain types of depreciation, manually adjust your expectations for the FTB bill.

- Consult a pro who knows California. A generic tax software might miss the specific nuances of California's "Other State Tax Credit" or the nuances of the PTE tax.

Understanding the "ladder" of California tax rates doesn't make the bill any smaller, but it does allow you to plan. Knowledge is the only way to keep the state from taking more than its fair share. Stop thinking about your total income and start thinking about your "last dollar" earned. That is where the real savings are found.