You’ve probably heard the song. Maybe it was the Grateful Dead version with the lyrics about cocaine, or maybe the old folk ballad that’s been floating around for over a century. It paints a picture of a wild, daredevil driver who went down in a blaze of glory. But honestly, the real story of Casey Jones train engineer is way more interesting than the myths—and a lot more tragic.

John Luther Jones wasn't some reckless guy with a death wish. He was basically a rockstar of the Illinois Central Railroad. He had this unique "whippoorwill" whistle that people along the tracks could recognize from miles away. They’d hear that long, mournful chime and say, "There goes Casey." He was 6-foot-4, a teetotaler, and a devoted family man.

The guy just really, really liked being on time.

The Night Everything Went Wrong at Vaughan

It was April 30, 1900. Casey wasn't even supposed to be working that night. He had just finished a run from Canton, Mississippi, to Memphis, Tennessee. He was tired. But when he heard that another engineer, Sam Tate, was too sick to pull the "Cannonball" southbound, Casey stepped up.

He didn't just take the shift; he took it while the train was already an hour and thirty-five minutes behind schedule.

For an engineer who lived by the motto "get there on the advertised," that delay was basically a personal insult. Casey opened the throttle on Engine No. 382. He was "highballing"—railroad slang for going as fast as the steel would allow. By the time he reached Goodman, Mississippi, he had clawed back almost all that lost time. He was flying through the night, telegraph poles blurring past like a picket fence.

Then he hit the S-curve at Vaughan.

A Freak Logistic Nightmare

Imagine three trains all trying to squeeze into a space meant for two. That’s essentially what happened. Two freight trains were trying to "saw by" each other on a siding to let Casey’s express pass. But one train was too long. It hung out onto the main track. To make matters worse, an air hose broke on one of the freights, locking its brakes and leaving its rear cars sitting right in Casey’s path.

It was foggy. The tracks were slick from rain.

Sim Webb, Casey’s fireman, was the first to see the red lights of the caboose. He screamed, "Oh my Lord, there’s something on the main line!"

Casey didn't hesitate. He yelled, "Jump, Sim, and save yourself!" Webb leaped into the darkness, getting knocked cold when he hit the ground. But Casey stayed. He stayed because if he didn't slow that train down, the hundreds of passengers behind him were going to die.

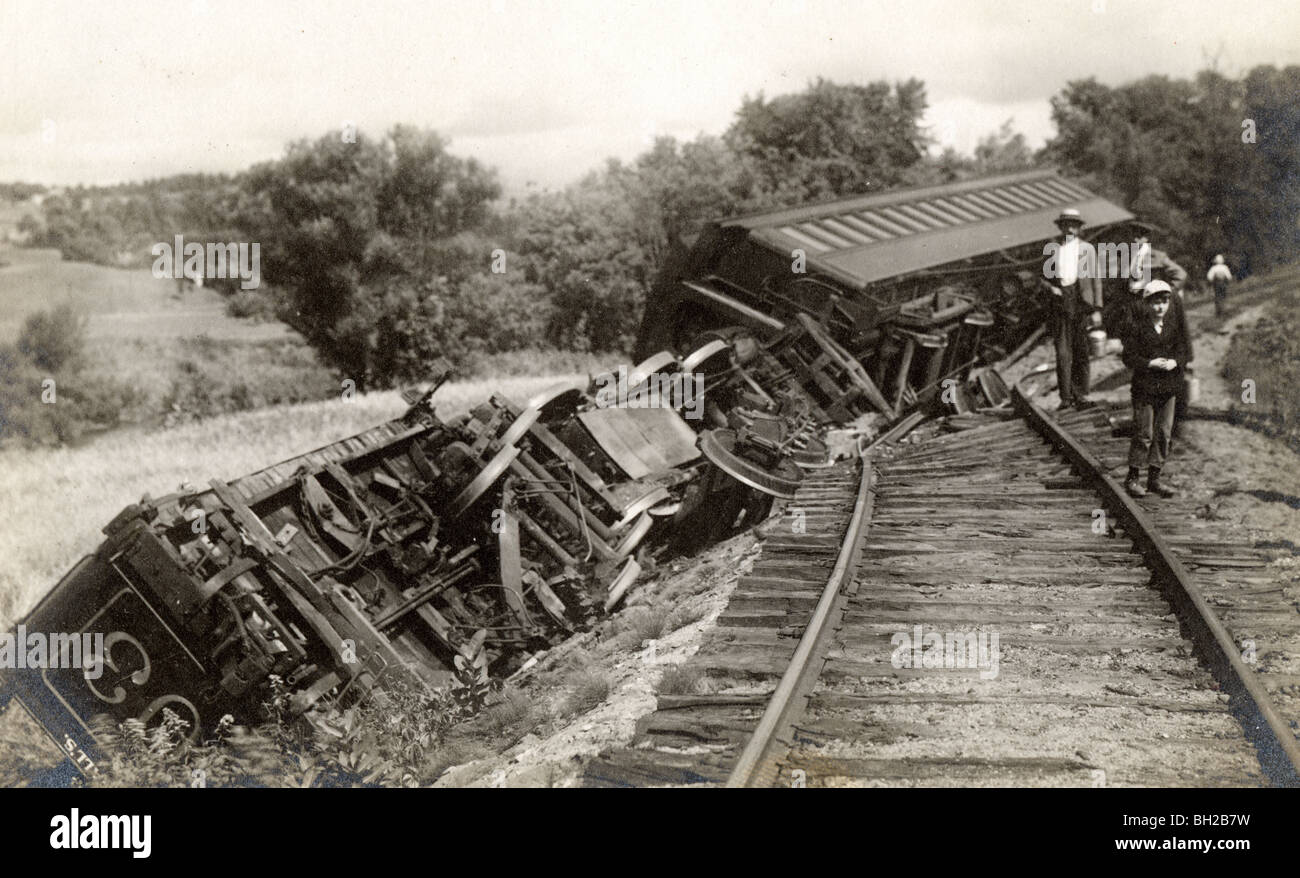

The Physics of the Crash

When they found him, Casey was dead. A piece of lumber had hit him in the throat. But here is the thing: he was the only person who died.

The Cannonball smashed through a caboose, a car full of hay, a car of corn, and halfway through a flatcar of lumber. Because Casey had stayed at the throttle, reversing the engine and slamming the emergency brakes, he'd slowed the train from 75 mph to about 35 mph before impact.

- Speed at the curve: ~75 mph

- Speed at impact: ~35 mph

- Fatalities: 1 (Casey himself)

If he had jumped with Sim Webb, the wreckage would have been a mass grave. Instead, the passengers walked away with little more than a few bruises and a story they’d tell for the rest of their lives.

👉 See also: Stacy Yovish in Phoenix Arizona: What You Actually Need to Know

Why We Still Talk About Him

The "Ballad of Casey Jones" wasn't written by some big-city songwriter. It was started by Wallace Saunders, an African American engine wiper who worked in the Canton roundhouse and knew Casey personally. He was just singing about a friend he respected.

Of course, the music industry got a hold of it later. They changed the lyrics, added some drama, and eventually, the Grateful Dead added the drug references that would have probably made the real, sober John Luther Jones pretty annoyed.

There’s also the weird "curse" of Engine 382. After the crash, the Illinois Central didn't scrap it. They rebuilt it. Over the next 35 years, that same locomotive was involved in multiple wrecks that killed several more people. It was eventually renumbered three times to try and shake the bad luck, but it didn't work. The engine finally hit the scrap yard in 1935, almost exactly 35 years after it killed the man who made it famous.

What Most People Miss

People often argue about whether Casey was at fault. The official railroad report blamed him for "disregarding signals." But Sim Webb maintained until his death in 1957 that they never saw a flagman or heard a warning torpedo. In the world of 1900 railroading, the pressure to stay on schedule was immense. Casey was doing exactly what the company expected of him—until the logistics failed.

How to Explore the History

If you’re ever driving through the South and want to see where this all actually happened, there are two main spots.

- Jackson, Tennessee: You can visit Casey’s actual home, which is now a museum. It’s right next to a replica of the 382.

- Vaughan, Mississippi: There’s a smaller museum at the site of the wreck. It’s quiet, a bit eerie, and it houses the original bell from the 382.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Read the official reports: Look up the Illinois Central accident report from 1900 to see how the company tried to shift blame.

- Listen to the variations: Compare the Wallace Saunders original lyrics to the Joe Hill union version (which portrays him as a "scab") to see how folk heroes are repurposed for different agendas.

- Check the physics: If you're into engineering, look up the "4-6-0 Ten Wheeler" specs to understand why stopping a train that size on a wet curve was practically impossible.

Casey Jones wasn't just a character in a song. He was a guy doing a dangerous job who decided his passengers' lives were worth more than his own leap into the bushes.

For your next steps, you can look into the history of the Illinois Central Railroad's "Cannonball" run to understand how high-speed mail delivery shaped the American South, or research the life of Sim Webb, whose testimony provides the only true counter-narrative to the official railroad report.