It happens every time a new trailer drops or a fresh comic run hits the stands. Someone online screams that Felicia Hardy is just a Marvel-branded knockoff of Selina Kyle. Or, if they’re feeling spicy, they claim DC "stole" the cat burglar trope from some obscure Golden Age pulp and polished it up for Gotham.

Honestly? It's way more complicated than just looking at who wore the ears first.

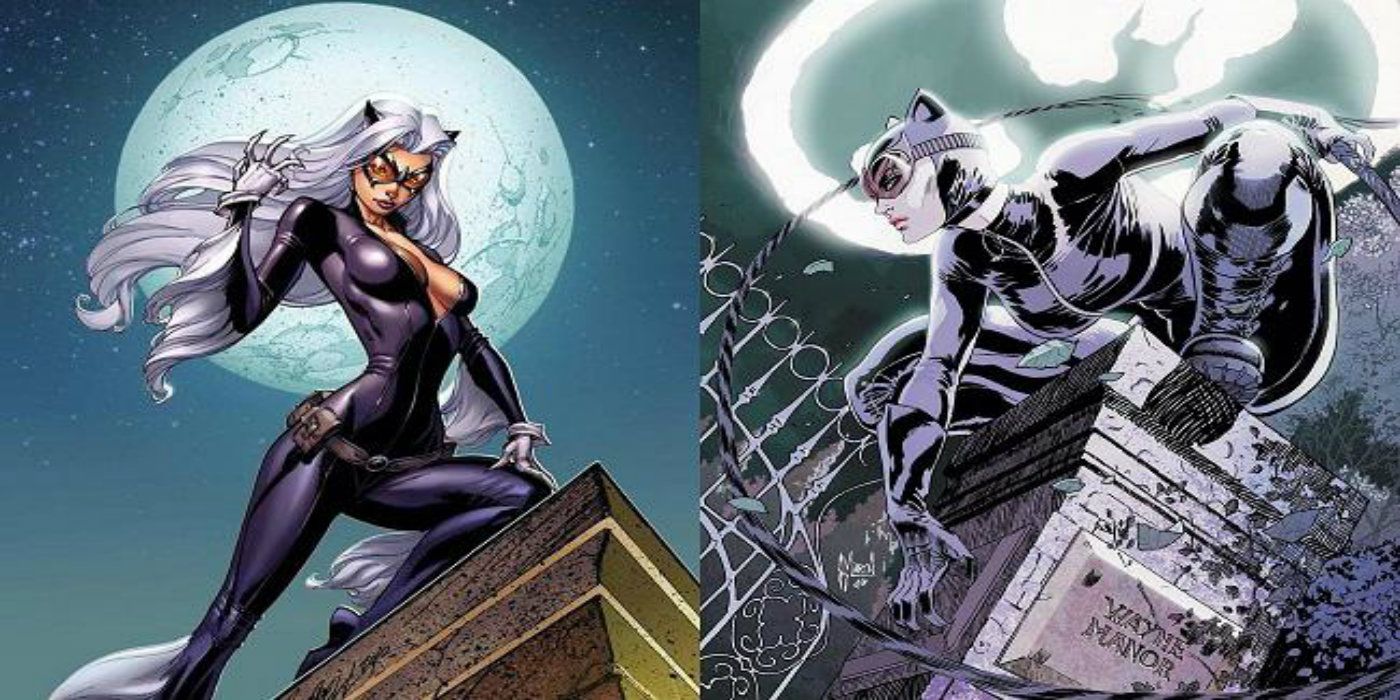

When you look at Catwoman and Black Cat, you aren't just looking at two women in spandex who like shiny things. You're looking at two completely different philosophies of the "femme fatale" archetype. One is a survivor of systemic rot who became a social justice warrior with a whip. The other is a thrill-seeker with literal "bad luck" powers who treats life like a high-stakes poker game.

Let's clear the air on the timeline first. Selina Kyle made her debut in Batman #1 back in 1940. She didn't even have a costume then; she was just "The Cat," a master of disguise in a green dress. Felicia Hardy didn't show up until The Amazing Spider-Man #194 in 1979. Yes, that’s a 39-year gap. But Marvel writer Marv Wolfman has gone on record stating he actually based Black Cat’s visual design on a Bad Luck Blackie cartoon, not DC's resident burglar.

The coincidence is real, but the characters have evolved into polar opposites.

The Gritty Reality of Selina Kyle’s Gotham

Selina Kyle is a creature of necessity. If you track her history from Frank Miller's Year One through to Joëlle Jones’ modern interpretation, her motivation is almost always grounded in protection. She grew up in the East End of Gotham. That place is a meat grinder.

She didn't start stealing because she thought it was a fun hobby. She did it because the foster system failed her and the streets were meaner than the people she eventually robbed. Catwoman is, at her core, a political character. She targets the wealthy elite of Gotham because she knows exactly how they stepped on people like her to get their billions.

There’s a specific weight to Selina. She carries the burden of the East End. When she steals a diamond, she’s often using the proceeds to fund a neighborhood watch or save a runaway. Her relationship with Batman works because they are two sides of the same trauma-informed coin. He uses fear to control the chaos; she uses theft to balance the scales.

It’s messy. She’s been a villain, an anti-hero, a member of the Justice League, and a mob boss. But she always comes back to the same thing: survival. She doesn't have superpowers. She has grit. She has a whip that she uses with the precision of a surgeon. She’s a world-class gymnast because if she slips, she dies. There's no "bad luck" aura to save her from a ten-story drop.

Felicia Hardy and the Luxury of the Thrill

Now, look at Felicia Hardy. The vibe shifts immediately.

📖 Related: Squid Games 1 Recap: The Darkest Moments We All Forgot

Felicia didn't grow up in a slum. She grew up as the daughter of a world-renowned cat burglar, Walter Hardy. Her entry into crime wasn't about putting food on the table; it was about legacy, rebellion, and—eventually—trauma recovery after a horrific assault in college. She chose to become the Black Cat to reclaim her power.

Unlike Selina, Felicia genuinely loves the game. She’s a thrill-seeker. While Catwoman is often brooding over the morality of Gotham, Black Cat is cracking jokes while vaulting over a laser grid. She has a playful, almost chaotic energy that mirrors Peter Parker’s own quips, which is why their chemistry is so electric.

Then there are the powers. People forget this. Black Cat actually has (at various times in her history) "probability manipulation." She literally makes bad things happen to people who try to catch her. This changes the stakes of her stories. Selina has to be perfect to survive. Felicia can be a little reckless because she knows the universe is tilted in her favor.

In recent years, especially under writers like Jed MacKay, Felicia has stepped out of Spider-Man's shadow. She’s not just "the girlfriend" anymore. She’s a master strategist who has outmaneuvered Iron Man and the Thieves Guild. She’s fun. She’s wealthy. She’s glamorous. She’s the person Selina Kyle would probably find incredibly annoying.

Why the "Copycat" Label Fails Both Characters

If you focus only on the catsuits, you miss the narrative function these characters serve.

Batman and Spider-Man are very different men. Batman is a billionaire playing at being a shadow; Spider-Man is a working-class kid trying to pay rent. Consequently, their "cat" counterparts serve as different mirrors.

- Catwoman challenges Batman’s rigid morality. She forces him to see the gray areas in a city he tries to see in black and white.

- Black Cat challenges Spider-Man’s sense of responsibility. She represents the freedom he could have if he stopped feeling guilty for five minutes.

There’s a famous scene in the comics where Peter Parker unmasks for Felicia, and she actually asks him to put the mask back on. She didn't want the man; she wanted the icon. Selina, conversely, fell in love with Bruce Wayne because of the broken man behind the cowl. That distinction is everything. It defines their entire publication history.

What Actually Matters When You Compare Them

If you’re trying to settle a debate at your local comic shop, stop looking at the costumes. Look at the "Why."

Selina is a protector.

Felicia is a performer.

Catwoman’s equipment is grounded. She uses pitons, whips, and claws. It’s all very "high-end tactical." Black Cat has used tech-enhanced earrings and contact lenses, but her primary "tool" is her ability to manipulate the environment through luck.

We also have to talk about their respective cities. Gotham is a Gothic nightmare. It’s dark, rainy, and oppressive. Selina’s stories reflect that atmospheric dread. New York City in the Marvel Universe is bright, crowded, and full of Avengers flying overhead. Felicia’s stories feel like heist movies—fast-paced, stylish, and a little bit ridiculous.

Moving Past the Comparison

To really appreciate these characters, you have to read their solo runs. Don't just look at them as love interests.

Check out Ed Brubaker’s run on Catwoman. It’s essentially a noir crime novel that happens to feature a woman in a leather suit. It’s grounded, brutal, and brilliant. On the flip side, grab the 2019 Black Cat series by Jed MacKay. It’s a riot. It’s a heist-of-the-week book that shows exactly how smart Felicia really is.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans:

- Audit your collection: If you’ve only seen them in movies (like Michelle Pfeiffer’s iconic turn or Anne Hathaway’s tactical take), go back to the source material. The films rarely capture the complexity of their internal monologues.

- Look for the 2020s runs: Both characters have had incredible solo titles in the last five years that distance them from their male counterparts.

- Focus on the creators: Follow writers who treat them as protagonists. When Catwoman is written as a "guest star" in a Batman book, she’s often simplified. When she’s the lead, she’s one of the most complex characters in fiction.

- Understand the legalities: Note that "Catwoman" is a mantle Selina has passed on or shared, while "Black Cat" is almost exclusively Felicia's identity.

The "who is better" debate is a dead end. The real value is in how these two women represent different ways to navigate a world that wants to put them in a cage. One breaks the bars with a whip; the other just waits for the lock to coincidentally fail. Both are essential.