If you look at a standard central africa region map, you’re probably seeing a massive, emerald-green block of land that looks relatively uniform. It isn’t. Not even close. People tend to treat this part of the world as one giant, humid jungle, but that’s a massive oversimplification that ignores the sheer geological and political complexity of the continent's heart. Honestly, most maps you find online are either outdated or fail to capture the nuance of where one "region" ends and another begins.

Depending on who you ask—the United Nations, the African Union, or a geologist—the borders of Central Africa shift like sand.

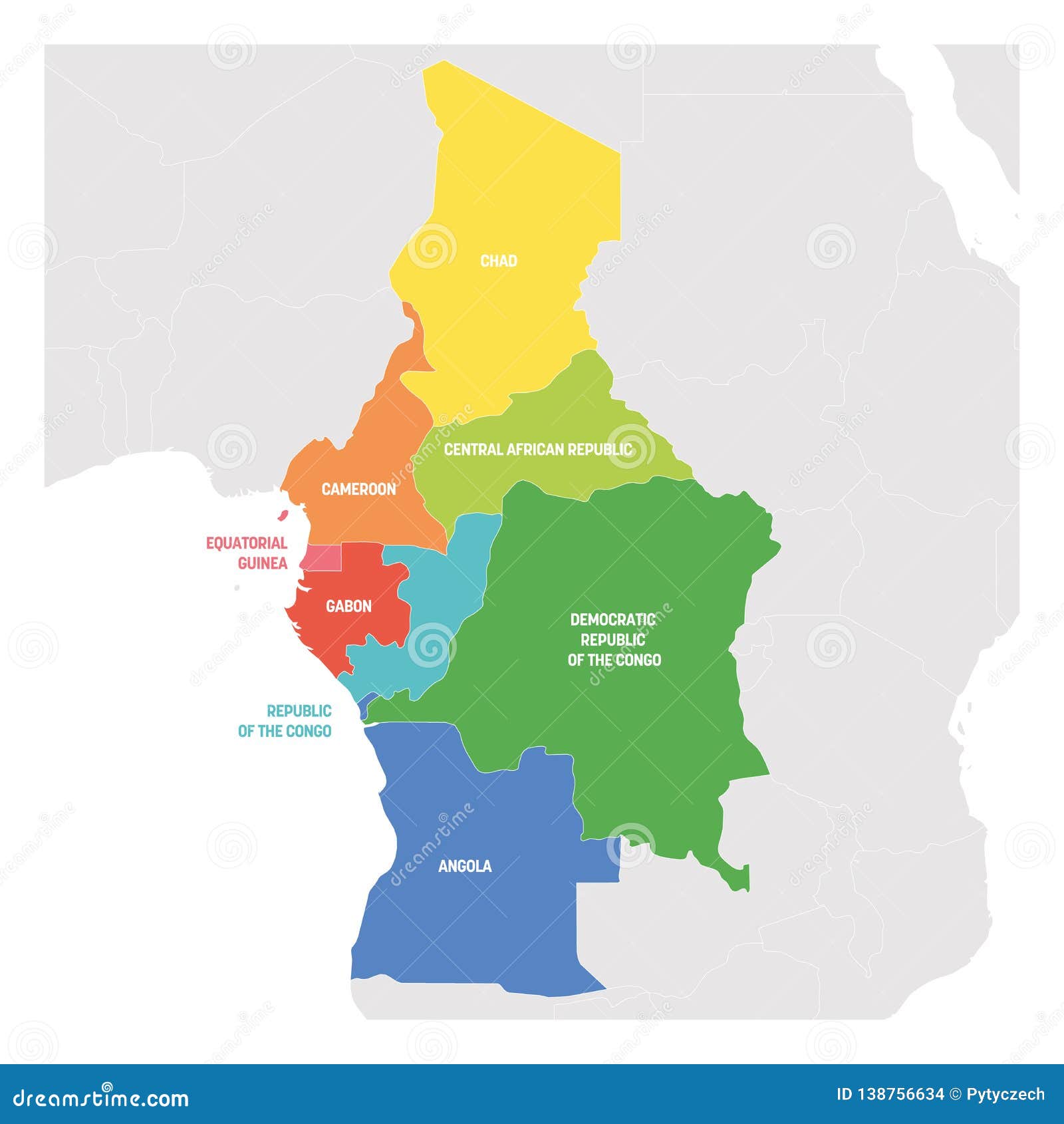

The UN says there are nine countries. Some geographers say there are eleven. It’s a mess, really. You’ve got the massive Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) sitting right in the middle, acting as the anchor, but then you have tiny island nations like São Tomé and Príncipe that are technically part of the same "region" despite being hundreds of miles out in the Atlantic. It’s a geographical puzzle.

The Fluid Borders of the Central Africa Region Map

Why is it so hard to pin down? Well, geography doesn't always care about politics.

The African Union's definition of Central Africa is different from the UN’s geoscheme. Usually, when we talk about a central africa region map, we are looking at the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). This group includes Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, the Congo, the DRC, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Rwanda, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

But wait. Look at Chad.

Chad is mostly desert in the north. It looks more like the Sahara or the Sahel than the lush rainforests of Gabon. Yet, it's firmly placed in the Central African category. Then you have Rwanda and Burundi. Historically and culturally, they are often lumped in with East Africa. They speak Swahili. They trade heavily with Tanzania and Kenya. But on many official maps, they are the eastern pillars of Central Africa.

It’s confusing.

Realities of the Congo Basin

You can't discuss this region without talking about the Congo Basin. It’s the literal lungs of the continent. If you zoom in on a central africa region map, the Basin is that vast, low-lying depression drained by the Congo River. This river is the deepest in the world. It’s a monster.

Most people don't realize that the Congo River actually flows in a massive counter-clockwise arc. It starts in the highlands of the East African Rift, shoots north, crosses the equator twice, and then dumps an unbelievable amount of water into the Atlantic.

- Gabon is nearly 90% forest.

- The DRC contains the second-largest rainforest on Earth.

- The CAR acts as a transition zone between the jungle and the dry savannas.

Geopolitically, the CAR is arguably the most "central" country on the continent. It’s landlocked. It’s isolated. It’s roughly the size of France but has a population smaller than New York City. When you see it on a map, it looks like a bridge connecting the Arab-influenced north with the Bantu-influenced south.

The High-Altitude Anomalies

Let’s talk about the mountains. People forget Central Africa has snow.

On the eastern edge of the central africa region map, you find the Rwenzori Mountains—the "Mountains of the Moon." These peaks reach over 5,100 meters. They have glaciers. Right on the equator. It’s wild. This mountainous spine, known as the Albertine Rift, creates a massive barrier that dictates the climate of the entire region. It traps moisture from the Indian Ocean, dumping it into the Congo Basin, which is why the region is so incredibly wet.

Then you have the Cameroon Line. This is a string of volcanoes that stretches from the Gulf of Guinea all the way inland. Mount Cameroon is an active volcano that literally rises out of the ocean. It creates a microclimate so wet that a place called Debundscha gets over 10,000 millimeters of rain a year. Imagine that. That’s nearly 33 feet of water falling from the sky every single year.

What Most People Miss About the Cities

Maps often show dots for cities, but they don't show the density. Kinshasa and Brazzaville are the two closest capital cities in the world, separated only by the four-mile-wide Congo River.

Kinshasa is a megalopolis. It’s on track to become one of the largest cities on the planet by 2100. When you look at a central africa region map, you see a lot of "empty" green space, but that space is rapidly urbanizing. The infrastructure, however, hasn't kept up. There are very few paved roads connecting these major hubs. In many parts of the DRC or the CAR, the river is the only highway that actually works.

If you’re trying to move goods from the coast of Gabon to the interior of the DRC, you aren't driving. You're barging. Or flying. This lack of "horizontal" connectivity on the map is why the region’s economy often feels fragmented.

The Economic Overlay

Central Africa is arguably the richest place on Earth in terms of raw materials, yet it’s the poorest in terms of GDP per capita.

The Katanga Plateau in the southern DRC is the world's "copper belt." It’s also where most of the world’s cobalt comes from. If you’re reading this on a smartphone or a laptop, there’s a high probability that a piece of a central africa region map is sitting in your pocket right now.

Gabon and Equatorial Guinea are different. They have oil. On a map, they look small, but their economic weight is massive because of offshore drilling. This creates a weird disparity. You have "Petro-states" with shiny skylines like Libreville next to countries like the CAR that struggle with basic electricity.

Understanding the "Central" Identity

Is there a "Central African" identity? Kinda.

📖 Related: Why Hotel Mascagni Rome Italy Is Actually a Better Move Than Staying Near the Pantheon

Most of the region shares a Bantu linguistic root. Whether you are in Douala or Lubumbashi, you’ll find linguistic similarities. French is the dominant colonial language, except in Equatorial Guinea (Spanish) and parts of Cameroon (English). This linguistic map is often just as important as the physical one.

The "Central African Republic" is the only country that actually uses the region's name as its own. It’s a bit on the nose, but it fits. It’s the heart of the heart.

Why You Should Care About the Map Today

Climate change is redrawing the central africa region map in real-time. The Lake Chad basin in the north has shrunk by about 90% since the 1960s. This isn't just a geography fact; it's a security crisis. As the water disappears, people move south. This causes friction between herders and farmers, leading to conflicts that we see in the news today.

Similarly, the peatlands discovered in the Cuvette Centrale region of the Congo Basin are a massive carbon sink. If that area—which looks like a simple swamp on most maps—is disturbed, it could release as much carbon as the entire world emits in three years.

Actionable Insights for Navigating the Region

If you are looking at a central africa region map for travel, business, or research, stop using the "all-encompassing" view.

- Differentiate by Biome: Separate your planning into the "Sahelian North" (Chad, northern CAR), the "Equatorial Core" (Congo, Gabon, DRC), and the "Highland East" (Rwanda, Burundi). They require entirely different logistics.

- Verify Border Crossings: Just because a map shows a road crossing between the DRC and the CAR doesn't mean it’s open or exists in a usable state. Always cross-reference with UN logistical maps (LogCluster).

- Use Digital Terrain Models: Standard flat maps hide the fact that much of the region is a series of plateaus. Elevation changes are the primary reason for the region's diverse weather patterns and agricultural zones.

- Follow the Water: If you want to understand where the population centers are, look at the river tributaries, not the roads. The Oubangui, the Sangha, and the Kasai rivers are the real arteries of Central Africa.

The central africa region map is a living document. It’s a place defined by its water, its incredible mineral wealth, and a topography that has protected its vast forests while complicating its political unity. Don't trust the flat green shapes on your screen; the reality is much more jagged, mountainous, and complex.