You’ve probably heard of the Adams family. Not the spooky ones with the butler, but the American royalty—the ones who basically lived in the White House for two generations. But there’s a guy in the middle of that family tree who usually gets ignored in favor of his more famous ancestors. Charles Francis Adams Jr. didn’t become President. Honestly, he didn’t even try. Instead, he became a soldier, a "sunshine" regulator, and eventually, the man who tried (and spectacularly failed) to save the Union Pacific Railroad.

He was a man caught between two worlds.

On one side, he had the crushing weight of the Adams legacy: John Adams and John Quincy Adams. On the other, he was staring down the barrel of the Gilded Age, a time of raw greed, steam engines, and corporate warfare. If you think modern tech monopolies are messy, you haven't seen anything until you look at how Charles Francis Adams Jr. tried to clean up the 19th-century railroad business.

The Soldier and the "Brahmin" Burden

Charles was born in Boston in 1835. He was a "Boston Brahmin" through and through. That sounds fancy, but it mostly meant he was expected to be brilliant, stiff, and miserable. He went to Harvard, naturally. He hated it. He thought his education was a "fetish" of the past, focusing on dead languages instead of the real world.

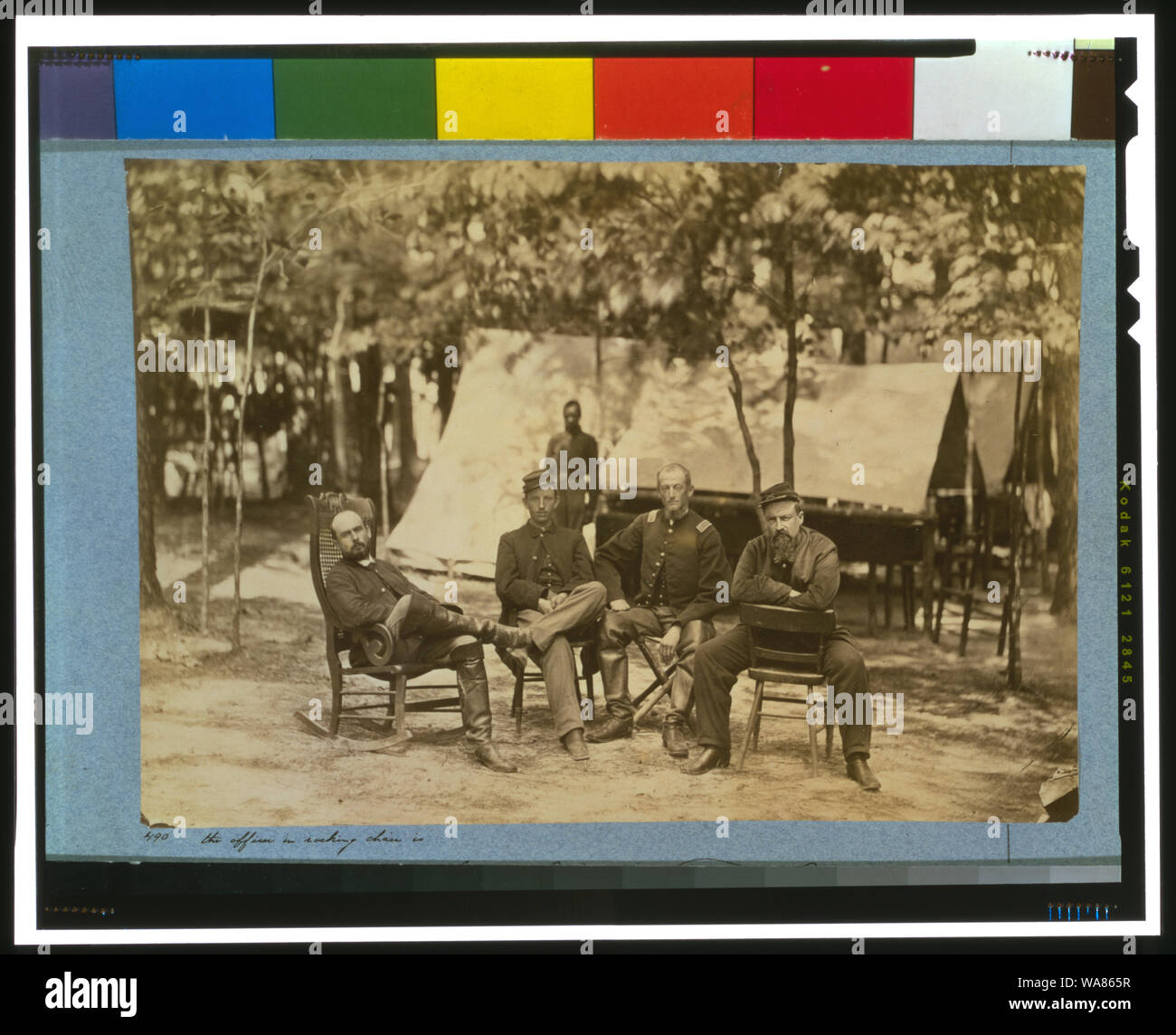

Then came the Civil War.

Most people in his social circle were buying their way out of service. Not Charles. He joined the First Massachusetts Cavalry and actually saw the elephant. He fought at Antietam and Gettysburg. By the end of the war, he was a Brigadier General leading the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry—a regiment of African American soldiers. He was one of the first Union officers to ride into a fallen Richmond.

That war changed him. It gave him a taste for leadership that didn't involve sitting in a dusty law office. When he got home, he looked at the growing railroad industry and saw a new kind of war.

What He Got Right About Big Tech... I Mean, Big Rail

In 1869, the "Golden Spike" was driven, and the transcontinental railroad was finished. It was the internet of its day. But it was also a cesspool of corruption. You had guys like Jay Gould and Jim Fisk literally printing fake stock certificates to steal companies.

Charles Francis Adams Jr. didn't have the stomach for the stealing, but he had a genius for the math.

He helped found the Massachusetts Board of Railroad Commissioners. This was the birth of modern regulation. He called it the "Sunshine Commission." His theory was basically: "If I show the public how much these guys are lying, the shame will force them to be honest."

"The railroad system has burst through State limits. Already not a few corporations have carried their operations into half the States of the Union."

He wrote that in 1871. He saw the future. He knew that if the government didn't step in, these private companies would eventually own the government. He wasn't a "man of the people" in a populist sense, though. He was a patrician. He wanted order. He wanted the railroads to run like a clock, not a casino.

The Union Pacific Disaster

In 1884, he got his big shot. He was named President of the Union Pacific Railroad. This was his chance to prove that a man of integrity could run a massive corporation without being a "robber baron."

It was a total train wreck.

Charles was great at writing essays about how a railroad should work. He was terrible at the dirty, day-to-day politics of the track. He tried to be fair. He set up libraries for his workers. He tried to improve safety. But he was also a man of his time, and when things got heated with unions, he made some brutal calls.

In 1885, his administration hired Chinese workers to break a strike in Wyoming. This led to the Rock Springs Massacre, where a mob of white miners murdered at least 28 Chinese laborers. It remains one of the darkest stains on his tenure.

💡 You might also like: Vanguard CEO Net Worth: Why It Is Not What You Think

By 1890, the debt was mounting. The "Robber Baron" himself, Jay Gould, maneuvered against him. Gould didn't care about "sunshine" or "integrity." He cared about the bottom line. He pushed Charles out, and Charles left the business world forever, bitter and exhausted.

The Historian Who Hated History Books

The last act of Charles Francis Adams Jr. is maybe his most interesting. He retreated to Quincy and Lincoln, Massachusetts, and became a historian. But he wasn't the kind of guy who just praised his ancestors.

He was actually quite critical. He wrote a biography of his father and a massive work called Three Episodes of Massachusetts History. He was obsessed with the truth, even if it made his family or his state look bad.

He served as the president of the Massachusetts Historical Society for twenty years. He basically invented the "scientific" approach to American history. No more myths. No more legends. Just the data.

Why we should still care

Honestly, we’re living through his world right now. Replace "railroads" with "social media" or "AI," and you have the exact same problem Charles was trying to solve: how do you regulate a force that is bigger than the law?

Next Steps for the History Buff:

If you want to understand the man behind the myth, don't start with a textbook. Read his autobiography, published posthumously in 1916. It’s surprisingly blunt. He talks about his failures, his regrets, and his frustrations with the "Brahmin" life.

You should also look into the Chapters of Erie, which he wrote with his brother, Henry Adams. It’s essentially a 19th-century true crime thriller about the fight for the Erie Railroad. It’ll show you exactly why Charles thought the business world was a "nest of vipers."

Finally, visit the Adams National Historical Park in Quincy. You can see the library where he worked and get a sense of the literal weight of history he was trying to carry. He didn't always succeed, but he was one of the few people of his era who actually tried to do things the "right" way.