Sending a professional message in Mandarin isn't just about plugging English sentences into a translator. It's actually a bit of a minefield. You’ve probably seen those templates online that look stiff or, worse, totally outdated. Honestly, the Chinese formal email format is as much about social hierarchy as it is about the actual words you’re typing.

If you mess up the opening, you’re basically telling the recipient you don't respect their position. That sounds dramatic, I know. But in a culture where "face" (mianzi) and seniority dictate most interactions, a misplaced comma or a "hey there" equivalent can stall a deal before it even starts.

The Hierarchy of the Salutation

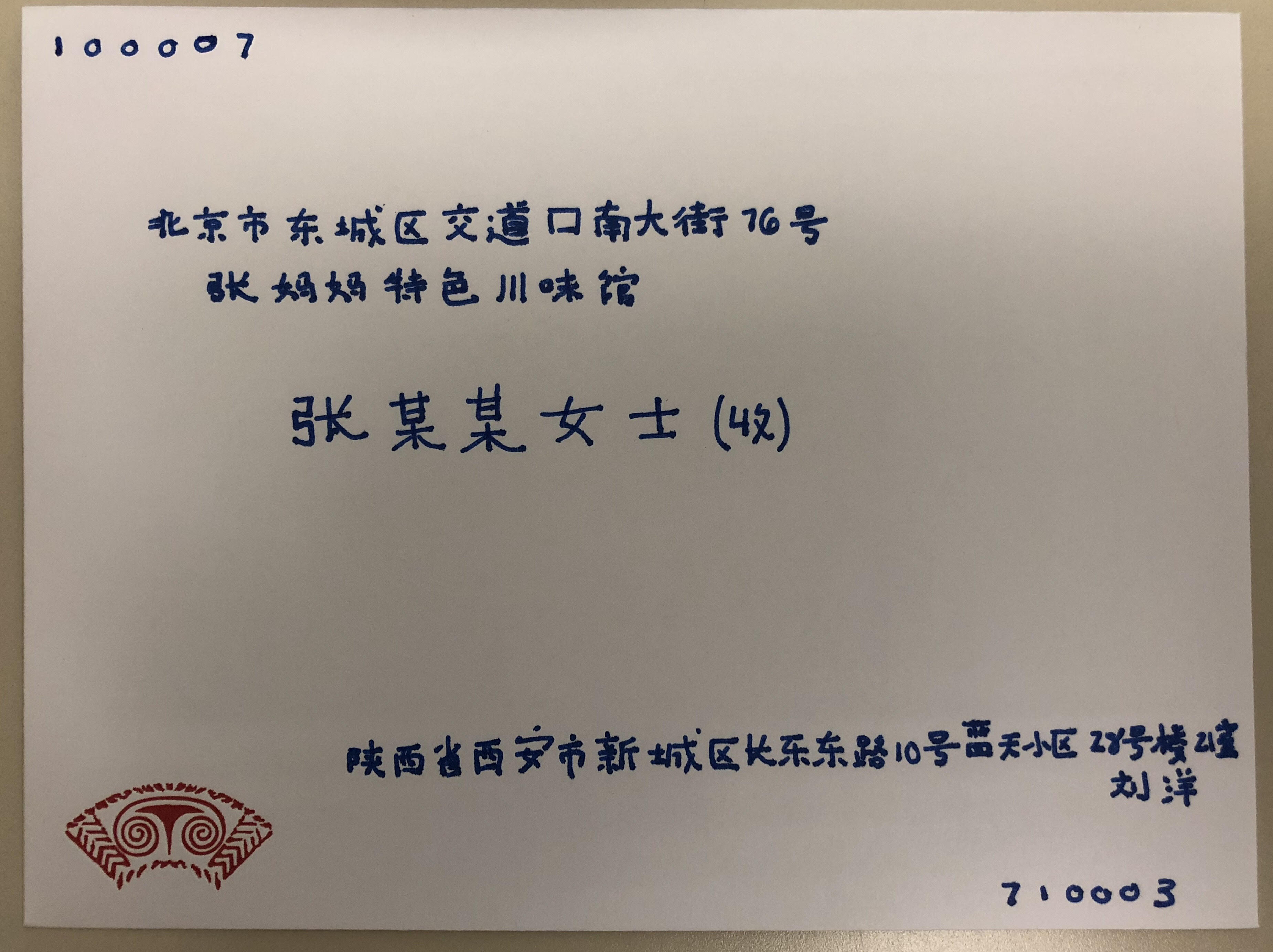

The first thing you have to nail is the greeting. In English, we’re used to "Dear [Name]." In China, it’s reversed. You put the surname first, then the title, then the honorific. Forget this, and the rest of the email barely matters.

Suppose you’re writing to a manager named Zhang Wei. You wouldn't say "Dear Zhang." You’d write Zhang Jingli (Manager Zhang) or, even better, Zhang Xian-sheng (Mr. Zhang). If they have a high-level title like Director (Zhongjian) or President (Zong), use it. Always.

📖 Related: Ways to Celebrate Company Milestones That Won't Make Your Employees Cringe

Why Nin Matters

You’ve likely heard of ni (you) and nin (the polite you). Use nin. Use it every single time you’re writing to someone older, more senior, or a potential client. It’s a tiny linguistic shift—adding a "heart" radical to the bottom of the character—but it changes the entire vibration of the message.

Sometimes people overthink the opening. They try to be overly poetic. Don't. A simple Nin hao (Hello) following the name and title is the gold standard. For a group, Geweitongzhi (Dear Colleagues) or Geweixiansheng/Nushi (Ladies and Gentlemen) works, though it feels a bit like a 1990s board meeting.

The "Opening Pleasantries" Trap

Western business culture often prizes brevity. "Get to the point," we’re told. If you do that in a Chinese formal email format, you’ll come across as abrasive. Or cold.

You need a "bridge" sentence.

Standard options include asking about their health or acknowledging the weather if it's particularly notable, but the most professional way is to reference a previous meeting or the current state of their business. Something like "Hope you have been well since our meeting at the Canton Fair" translates to a genuine interest in the relationship rather than just the transaction.

Examples of the Hook

- Zui jin hao ma? (How have you been lately?) - A bit casual, but okay if you've met once.

- Xi wang nin yiqie shunli. (I hope everything is going smoothly for you.) - This is the "safe bet" for almost any professional context.

It's basically about building a cushion before you drop your request or your data.

Structuring the Core Message

Once you’ve done the polite dance, you get to the point. But even here, the structure differs from Western expectations. In the US or UK, we often lead with the "Ask." In a formal Chinese context, you provide the context first, then the request.

Explain the "Why" in detail. If you need a report by Friday, don't start with the deadline. Start with the project’s importance, the progress made so far, and then mention the deadline as a logical next step to ensure success.

Keep your sentences clear. Avoid idioms (chengyu) unless you are absolutely certain of their nuance. Using a four-character idiom incorrectly is worse than not using one at all; it makes you look like you're trying too hard to "act Chinese" without understanding the depth of the language.

The Tone Shift

You want to be humble. In Chinese business culture, being self-deprecating is a power move. Using phrases like Qing duoduo zhijiao (Please give me your guidance) at the end of a proposal doesn't mean you're incompetent. It means you're respectful. It shows you value their expertise.

The Closing and the "Wish"

How you end the email is just as rigid as how you start it. You don’t just say "Best" or "Thanks."

The most common formal closing is Cizhi Jingli. You’ve probably seen this and wondered why it’s broken up. Cizhi means "with this" and Jingli means "respectful salutation." Usually, you put Cizhi on its own line after the body text, and Jingli on the following line, indented or aligned differently.

Common Sign-offs to Keep in Your Pocket

- Zhu, Shang-an. (Wishing you business peace/prosperity.)

- Zhu, Gongzuo shunli. (Wishing you smooth work.)

- Shun song shang qi. (Wishing you seasonal blessings—very formal, very old school.)

Honestly, most modern tech companies in Beijing or Shanghai are moving toward a slightly more relaxed vibe, but if you’re dealing with State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) or traditional manufacturing firms, stick to the classics. They appreciate the effort.

✨ Don't miss: The Liquidator of Irvington: What Really Happened with the Business

Real-World Nuances and Common Fails

One thing people forget is the "cc" culture. In many Chinese firms, who you copy on the email is a massive statement of hierarchy. If you omit a senior leader who was in the room during a meeting, it’s a slight. If you include someone too high up for a trivial matter, you’re "disturbing the peace."

Also, pay attention to the time you send it. While "hustle culture" is real, sending a formal email at 2 AM on a Saturday can sometimes be seen as a lack of boundaries rather than hard work, depending on the industry.

The Attachment Etiquette

Don't just attach a file and say "See attached." List what the files are in the body of the email. Label them clearly in Chinese if possible, or at least a bilingual format. Fujian (Attachment) should be clearly marked so they don't have to hunt for what you're talking about.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Email

- Audit your recipient's title. Look at their LinkedIn or company "About Us" page. If they are a "Vice General Manager," do not call them "Manager." Use the full title.

- Switch to 'Nin'. Go through your draft and replace every instance of ni with nin. It takes two seconds and changes the entire tone.

- The 'Double Check' on Names. Chinese surnames come first. If you see "Wang Xiaoming," Mr. Wang is the surname. Do not call him "Mr. Xiaoming." This is the most frequent "laowai" (foreigner) mistake and it’s an instant credibility killer.

- Format the Sign-off. Use the two-line Cizhi / Jingli format. It shows you actually researched the Chinese formal email format rather than just using a generic template.

- Simplify your English. If you’re writing in English to a Chinese partner, use "SVO" (Subject-Verb-Object) sentences. Avoid sarcasm. Sarcasm does not translate in text, especially across cultures.

By focusing on these structural markers—the "heart" in your pronouns, the order of the name, and the specific two-line closing—you signal that you aren't just a visitor, but a serious professional who respects the culture. It moves the needle from "another foreign vendor" to "a respectful partner."