You step out of Union Station, take a deep breath, and... what exactly are you inhaling? Most people think Toronto is "clean," at least compared to the smog-choked megacities of Asia or even the grit of New York. But honestly, the city of Toronto air quality is a lot more complicated than a simple "good" or "bad" rating on your weather app. It's a shifting, invisible landscape of nitrogen dioxide from the 401, fine particulate matter from wildfires thousands of kilometers away, and a weird cocktail of chemicals that settle in the lakefront basins during a humid July heatwave.

It's actually pretty decent most days.

But "decent" isn't the same as "safe" for everyone, especially if you're living in a basement apartment near the Gardiner or jogging through Liberty Village during rush hour. We’ve spent decades cleaning up the air by shutting down coal plants—the Nanticoke Generating Station closure was a massive win for Ontario—but we replaced that industrial smog with a different beast: traffic.

Why the city of Toronto air quality feels different lately

Have you noticed those hazy, orange-tinted sunsets? They aren't just pretty. Over the last few years, specifically since the record-breaking 2023 wildfire season, the conversation around Toronto’s air has shifted. We used to worry about local factories. Now, we're worried about Quebec, Northern Ontario, and even Alberta. When those fires rage, the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) in the GTA can spike from a comfortable 2 or 3 to a "stay inside and keep your windows shut" 10+.

✨ Don't miss: The Blood Sugar Levels Watch: Why We’re Still Waiting for the Holy Grail of Health Tech

The city is a bit of a geographical trap.

Toronto sits in a bit of a bowl. To the south, you've got Lake Ontario. When the weather is right—or wrong, depending on how you look at it—a "lake breeze" effect can actually pin pollutants against the Escarpment or trap them right over the downtown core. It's called an atmospheric inversion. Basically, warm air acts like a lid on a pot, keeping all the bus exhaust and construction dust right at street level where you're walking your dog.

The $PM_{2.5}$ problem

This is the stuff that actually matters. When experts talk about the city of Toronto air quality, they are obsessed with $PM_{2.5}$. These are particles smaller than 2.5 microns. How small? Think about a human hair. Now imagine something thirty times smaller than that. These particles are tiny enough to bypass your lung's filters and go straight into your bloodstream.

In Toronto, this mostly comes from:

- Brake wear and tire fragments (yes, even from EVs).

- Old diesel trucks idling in Kensington Market.

- Wood-burning fireplaces in the older, wealthier pockets of the city.

- Massive infrastructure projects like the Ontario Line construction.

The "Zip Code" health gap

It’s kind of a harsh reality, but your air quality depends on your rent. If you live in a high-rise in Yorkville, you’re breathing different air than someone living in a community housing complex right next to the 401 or the Don Valley Parkway. Studies by researchers at the University of Toronto, like Dr. Greg Evans at the Southern Ontario Centre for Atmospheric Aerosol Research (SOCAAR), have shown that pollutant levels can be three to four times higher right next to major highways compared to just two blocks away.

That’s a huge delta.

If you're within 200 meters of a major road, you're in the "hot zone." The city of Toronto air quality isn't a monolith; it's a patchwork. The residents in Scarborough near industrial zones or those in the West End near the "Spaghetti Junction" deal with a baseline of pollution that someone in the middle of High Park just never sees.

The hidden impact of the Gardiner Expressway

We talk about the Gardiner in terms of traffic jams and crumbling concrete. We rarely talk about it as a lung irritant. But for the thousands of people moving into those glass condos lining the highway, the air quality is a daily struggle. Even with high-grade HVAC filters (MERV 13 is the gold standard), the fine dust—black, grimy soot—finds its way onto balconies and into living rooms. It’s a trade-off for the view.

Is the city doing anything about it?

Toronto has the "TransformTO" Net Zero Strategy. It sounds like a typical government slogan, but there's some meat to it. The goal is to hit net-zero emissions by 2040. They're pushing for electric buses (the TTC has one of the largest e-bus fleets in North America) and trying to mandate greener building standards.

But here is the catch.

The city is growing too fast for the infrastructure to keep up. More people means more deliveries. More deliveries mean more vans. More vans mean more idling in bike lanes. It’s a cycle. While we’ve eliminated the big "Point Source" polluters—the heavy industry of the mid-20th century—the "Non-Point" sources (us, basically) are harder to manage.

📖 Related: Why a boil on bikini line keeps happening and what actually works to fix it

Real talk: How to actually protect yourself

You can't move the 401, and you can't stop a wildfire in the boreal forest. So, what do you actually do? Monitoring the city of Toronto air quality is the first step, but you have to look at the right data.

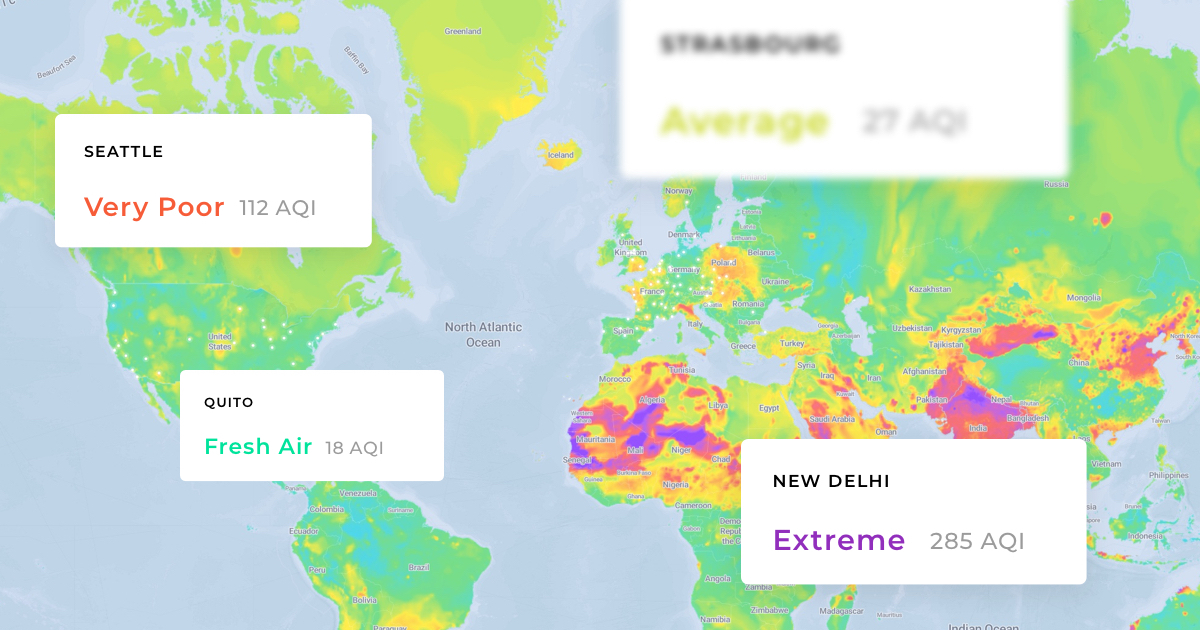

The standard AQHI is okay, but it's often an average. If you want the truth, look at hyper-local sensors. PurpleAir maps often show a much grittier, more localized version of what's happening in your specific neighborhood compared to the official government station at Toronto Downtown (which is often tucked away in a relatively "clean" spot).

Practical steps for the average Torontonian

- Check the wind, not just the temp. If the wind is coming from the south/southwest, it's often bringing up pollution from the industrial US Midwest. If it's a northern breeze, you're usually getting that crisp, clean Canadian Shield air.

- HEPA is your best friend. If you live near a construction site or a major road, an air purifier isn't a luxury; it's a health necessity. Make sure it's a true HEPA filter, not "HEPA-like."

- Morning commutes are the worst. $NO_2$ levels usually peak between 7:00 AM and 9:00 AM. If you're a runner, try to hit the trails in the evening or early afternoon when the air has had a chance to circulate, or stay deep in the ravines where the trees act as a natural buffer.

- The "Smell Test" is a lie. Some of the most dangerous pollutants in Toronto, like Carbon Monoxide or certain VOCs, don't have a smell. Don't assume the air is clean just because it doesn't smell like a tailpipe.

- Watch the humidity. Toronto’s "humidex" days are notorious for more than just sweat. High humidity holds pollutants in place. On those "Air Quality Advisory" days, the city often offers free transit or opens cooling centers—use them.

The reality of city of Toronto air quality is that we are doing better than we were in the 1980s, but the challenges are becoming more "global" and less "local." We are at the mercy of the climate. When the jet stream dips and brings smoke down, or when a heat dome sits over the Golden Horseshoe, the air gets thick.

If you're sensitive to asthma or have heart conditions, these "minor" fluctuations in the city of Toronto air quality are a big deal. The city is working on it, but the best defense is personal awareness. Get an app that gives you real-time $PM_{2.5}$ alerts, invest in a good indoor filter, and maybe avoid jogging right next to the DVP during the Tuesday morning rush.

👉 See also: Can I stop Tamiflu after 3 days? Here is why your doctor says no

Immediate Actionable Steps:

- Download the AirVisual or WeatherCan app to get push notifications for air quality alerts specifically for the Downtown, North York, or Etobicoke stations.

- Upgrade your home furnace filter to a MERV 11 or MERV 13 rating if your system can handle the static pressure; it catches significantly more traffic-related particles.

- Seal your windows during wildfire season using simple weatherstripping to prevent "seepage" of fine particulates into your sleeping area.

- Plan outdoor exercise using the City of Toronto’s real-time traffic maps—if the roads are red, the air nearby is likely in the "unhealthy for sensitive groups" range.