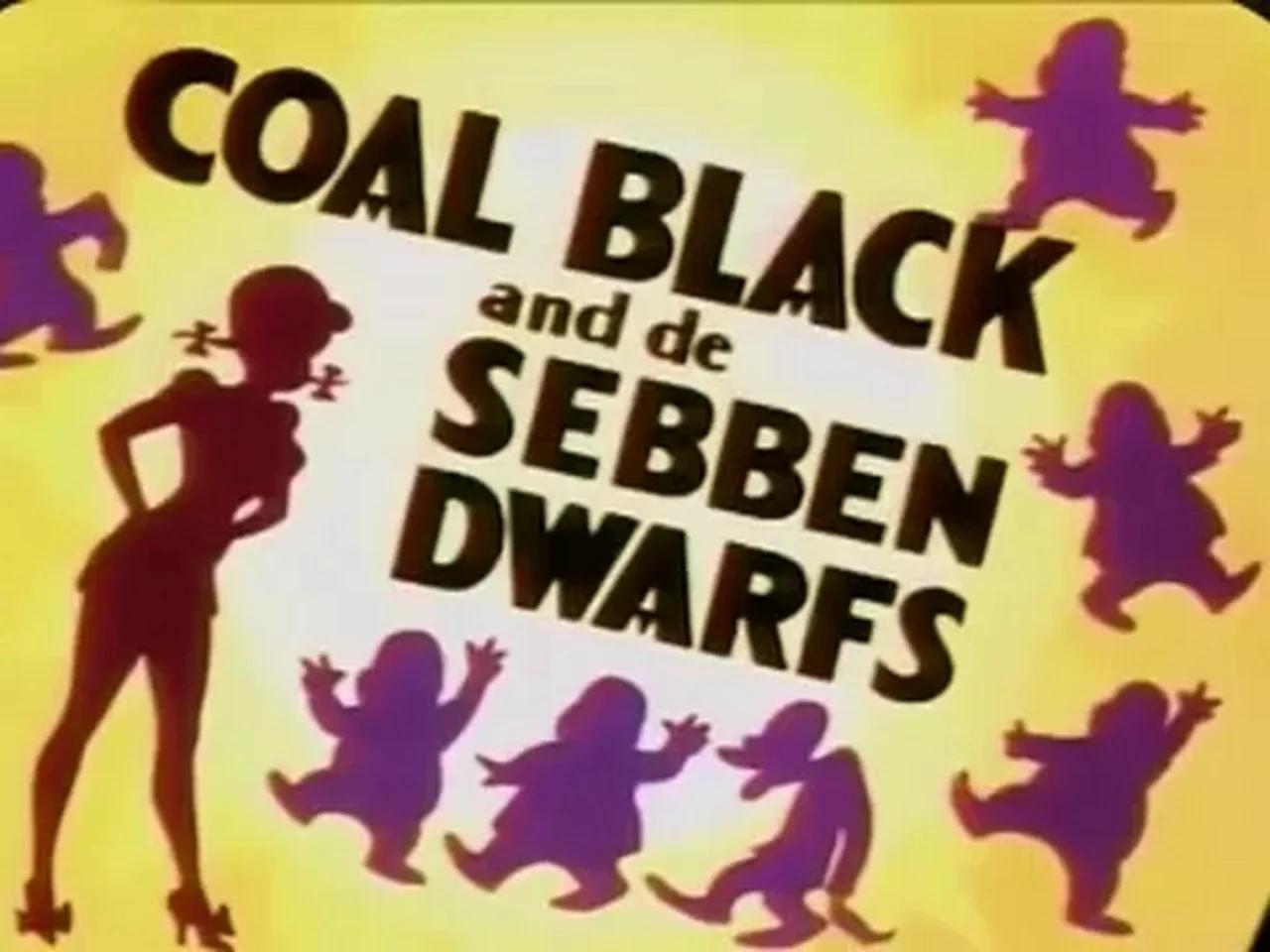

You’ve probably heard of the "Censored Eleven." It’s that list of Looney Tunes shorts so controversial they were pulled from rotation in 1968 and haven't officially been seen on TV since. Among them, one title stands out like a neon sign: Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs.

Released in 1943, this Bob Clampett masterpiece is a seven-minute fever dream. It’s a parody of Disney’s Snow White, but swapped into a WWII-era jazz setting with an all-Black cast. It is, simultaneously, one of the most visually stunning pieces of animation ever produced and one of the most racially insensitive. Honestly, it’s a lot to wrap your head around.

To some, it’s a hateful relic of Jim Crow-era "darky" iconography. To others, specifically animation historians, it’s a brilliant celebration of jazz culture that was actually ahead of its time in some weird, contradictory ways.

The Wild Origin Story of "So White"

The cartoon didn't just pop out of thin air. Director Bob Clampett was a massive jazz fan. In 1941, he went to see Duke Ellington’s musical revue Jump for Joy in Los Angeles. Legend has it that Ellington and his cast actually suggested that Clampett make a musical cartoon focused on Black culture.

Clampett didn't just stay in his office and draw. He took his animation team on field trips to Club Alabam, a legendary Black nightclub in LA. They watched the dancing, soaked in the music, and tried to capture that specific "swing" energy.

A Quest for Authenticity (Sorta)

Clampett wanted an all-Black band to do the score, similar to how the Fleischer Studios used Cab Calloway for Betty Boop. But producer Leon Schlesinger was cheap. He didn't want to pay for an outside band when he already had Carl Stalling on the payroll.

Still, Clampett pushed back. He managed to hire Eddie Beals and His Orchestra to record the trumpet solos for the final scene. He also cast Black actors for the leads—Vivian Dandridge (sister of the famous Dorothy Dandridge) voiced the main character, So White, and her mother, Ruby Dandridge, voiced the Queen.

Why It Ended Up Banned

If everyone was having such a great time making it, why did the NAACP call it a "disgraceful" image just months after its release?

Basically, the character designs are rough. We’re talking about the standard 1940s caricatures: massive lips, "pair o'dice" for teeth on Prince Chawmin’, and a Stepin Fetchit-inspired dwarf. Even though the animation is fluid and the timing is genius, the visual language is rooted in minstrelsy.

The War Effort Context

There's also the WWII angle. The dwarfs aren't miners; they’re an all-Black military unit. The NAACP argued that depicting Black soldiers as "dwarfs" was insulting to the men fighting overseas.

Interestingly, the cartoon is filled with war-time references:

- The Queen is hoarding vital war rations like coffee and sugar.

- "Murder Inc." offers to kill "Japs Free."

- So White declares she’s "wacky over khaki."

By 1968, the world had changed. The Civil Rights Movement had happened. United Artists, who owned the library at the time, decided these cartoons were just too radioactive for television.

The "Masterpiece" Debate

Here is the thing: if you talk to professional animators today, many will tell you Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs is one of the greatest cartoons ever made. In Jerry Beck’s 1994 book The 50 Greatest Cartoons, it was voted #21 by a panel of 1,000 industry pros.

💡 You might also like: Why the 1983 Legend of the Condor Heroes is Still the Only Version That Matters

Why? The energy.

The animation by Rod Scribner and Robert McKimson is explosive. The characters don't just move; they vibrate. There’s a scene where a strip of bacon cooks in rhythm to the music that is just... chef's kiss. It’s a masterclass in "squash and stretch" and rhythmic timing.

"Clampett was given a standing ovation by a predominantly Black audience in the city of Oakland." — Floyd Norman, legendary Disney animator.

Norman has often defended the short, arguing that while the designs are dated, the spirit of the cartoon was one of admiration for the "hip" jazz culture of the time, not mockery. It’s a complicated legacy.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often assume these cartoons were made by hateful people trying to demean others. While there was certainly systemic racism at play, the reality is more nuanced. Clampett saw himself as a fan. He thought he was being "authentic" by hiring Black musicians and actors.

But intent doesn't always negate impact. The "shorthand" of 1940s animation was inherently based on stereotypes. Even when the creators thought they were being complimentary, they were using a visual vocabulary that we now recognize as harmful.

Is it actually "Banned"?

Not exactly. The government didn't ban it. Warner Bros. (and previous owners) simply chose not to sell it or air it. It’s a corporate decision, not a legal one. You can actually find it on the Internet Archive or in bootleg circles pretty easily. It even had a rare official screening at the TCM Classic Film Festival in 2010 with a scholarly introduction.

Actionable Insights: How to Approach the "Censored Eleven"

If you're interested in animation history, you can't just ignore these films. They exist. But how do you watch them without feeling like a jerk?

- Watch with Context: Don't just watch it as a "funny cartoon." Look at it as a historical document of 1943 America.

- Study the Artistry: Ignore the character designs for a second and look at the movement. Notice how the animation syncs with Carl Stalling's score. It’s genuinely impressive technical work.

- Read Diverse Perspectives: Look up what Black animators like Floyd Norman or historians like Christopher P. Lehman have to say. Their takes provide the "why" behind the controversy.

- Acknowledge the Evolution: Use these films to see how far media representation has come. It’s a benchmark for progress.

Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs is a reminder that art doesn't exist in a vacuum. A film can be a technical "masterpiece" and a social "disaster" at the same time. Understanding that duality is the key to being a smart media consumer.