It happened in a second. Maybe you slipped on a patch of black ice, or perhaps a heavy cabinet door swung open right as you stood up. That sickening thud at the base of your skull isn't just painful; it’s different from a bump on the forehead. When we talk about a concussion back of head impact, we’re dealing with a specific set of neurological risks that often get lumped in with general "head bonks." They shouldn't be.

The back of your head houses the occipital lobe and sits right above the brainstem. It’s the mission control for your vision and the literal bridge to your spinal cord. Honestly, a hit here can rattle your entire sensory system in ways a frontal impact might not. You aren't just dealing with a headache; you're dealing with how your brain interprets the world.

The "Contrecoup" Effect: Why the Front Hurts When You Hit the Back

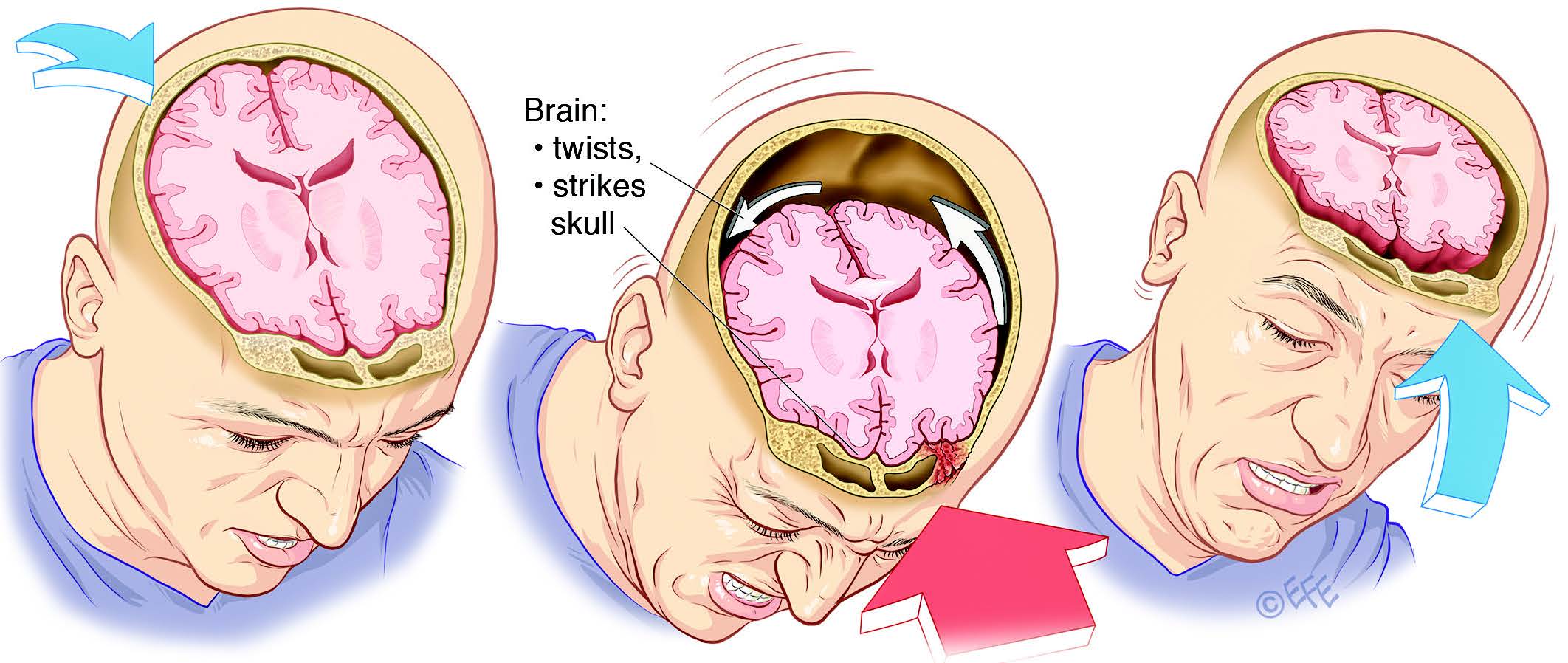

Here is something most people don't realize about a concussion back of head injury. The spot where you hit your skull isn't always where the most damage happens. Think of your brain like a piece of Jell-O inside a plastic container. When you whack the back of that container, the Jell-O slides backward, but then it slams forward into the front of the skull. This is what doctors call a contrecoup injury.

👉 See also: Hamstring Pain and Posterior Upper Leg Muscles: What Your Gym Routine Is Missing

Basically, you might hit the back of your head, but your frontal lobe—the part of your brain responsible for personality, decision-making, and "filter"—takes a massive hit too. This is why some people who fall backward suddenly find themselves incredibly irritable or unable to focus on a simple grocery list. Dr. Robert Cantu, a leading expert in neurosurgery and concussions, has often pointed out that the brain's movement within the cerebrospinal fluid is chaotic. It’s not a straight line. It’s a slosh. That sloshing tears microscopic fibers called axons. You can't see this on a standard CT scan, which is why your ER doctor might say the scan is "clear" even though you feel like garbage. A CT scan looks for bleeding and cracked bones, not the metabolic crisis happening inside your neurons.

Vision and the Occipital Lobe

The occipital lobe is tucked right at the rear. Its one job? Processing what you see. When you suffer a concussion back of head, your "visual hardware" gets shaken. You might see "stars," which are actually just your neurons firing randomly due to the physical shock. But it goes deeper than that. Many patients report that their depth perception feels "off." Or maybe the fluorescent lights in the pharmacy suddenly feel like they're drilling into your brain.

This photophobia is a hallmark of occipital trauma. Your brain loses its ability to modulate light. It's overwhelmed. You might also experience "visual snow" or a slight lag when you move your eyes from left to right. It’s unsettling. You feel disconnected from your environment.

The Sneaky Danger of the Brainstem

The base of the skull is the gateway to the brainstem. This area controls the stuff you don't think about: heart rate, breathing, and sleep-wake cycles. If the force of the impact was enough to cause a concussion back of head, it likely sent vibrations down toward the cerebellum and brainstem.

Have you noticed you're suddenly dizzy? Not just "woozy," but a genuine sense that the floor is tilting? That’s often the vestibular system being thrown out of whack. The cerebellum, located right there at the back, coordinates your movement. If it’s bruised or inflamed, you’ll walk like you’ve had three martinis when you’ve had none. Honestly, it's one of the most frustrating parts of recovery because it makes simple tasks like walking down stairs feel like a high-wire act.

🔗 Read more: Jillian Michaels Exercise Program: What Most People Get Wrong

Symptoms That Demand Your Attention

Don't ignore the weird stuff. A concussion is a functional injury, not a structural one. Your brain is having an energy crisis. It’s trying to heal, but it’s burning through fuel (glucose) at an insane rate to fix the cellular damage.

- The Pressure Headache: It feels like your skull is three sizes too small.

- Delayed Nausea: You felt fine right after the fall, but six hours later, you can't look at food.

- Tinnitus: A high-pitched ringing that won't quit. This is common with rear impacts because of the proximity to the inner ear structures and the acoustic nerves.

- Emotional Volatility: Crying over a dropped spoon? That's the frontal lobe struggling to regulate after the contrecoup movement.

There is a real risk of something called Second Impact Syndrome (SIS). While rare, it's catastrophic. If you hit your head again before the first concussion back of head has healed, your brain can lose its ability to regulate intracranial pressure. This is why "toughing it out" is actually dangerous. You’re not being a hero; you’re gambling with your brain's ability to keep itself alive.

The 48-Hour Rule and Beyond

The first two days are the "red zone." You need cognitive rest. This doesn't just mean lying in the dark—though that helps. It means no screens. The blue light and the rapid flickering of a phone screen (even if you can't see the flicker) are like a strobe light to an injured occipital lobe. It’s exhausting.

Rest is the only way to close the "energy gap." In the days following a concussion back of head, your brain's blood flow actually decreases slightly, even though it needs more nutrients to heal. It’s a paradox. If you push yourself by trying to work a 40-hour week or going to a loud concert, you’re just extending your recovery time by weeks, maybe months.

✨ Don't miss: Why child cancer research funding cut decisions are stalling real cures

When to Hit the Emergency Room

I'm not a doctor, but the clinical guidelines from organizations like the Mayo Clinic and the CDC are pretty clear on the "red flags." If you or someone you're watching exhibits these, stop reading and go to the ER:

- One pupil is larger than the other (anisocoria).

- Seizures or tremors.

- Inability to recognize people or places.

- Repeated vomiting—not just once, but multiple times.

- Slurred speech that sounds like intoxication.

Real Recovery Steps That Actually Work

Recovery isn't just "waiting." It's active management. After the initial 48 hours of rest, total isolation can actually make things worse. You start to get depressed. You focus too much on the pain.

- Sub-Symptom Exercise: Once the initial fog clears, very light walking can help. The key is "sub-symptom." If you start to feel a headache, stop. You're trying to encourage blood flow without triggering the energy crisis.

- Neck Assessment: A huge percentage of people with a concussion back of head also have "cervicogenic" issues. Basically, you gave yourself whiplash. The nerves in your neck can cause headaches that mimic concussion symptoms. A physical therapist specializing in the cervical spine can be a godsend.

- Hydration and Magnesium: Your neurons are struggling with ion imbalances. Drinking plenty of water and talking to a doctor about magnesium threonine (which crosses the blood-brain barrier) can sometimes help with the post-concussion "brain fog."

- Screen Filters: Use "Night Mode" on everything. Lower the contrast. It saves your visual processing centers from overworking.

The Nuance of the "Back of Head" Impact

We often talk about concussions as if the brain is a monolith. It isn't. The back of the head is the structural "basement" of the skull. It's thicker bone than the temples, but the stuff underneath is more vital for basic survival. A hit to the forehead might change how you plan your day, but a hit to the back of the head changes how you see the world—literally.

Listen to your body. If you feel like your "processor" is running at 20% capacity, it's because it is. Your brain has rerouted all its power to the repair crews. Let them work.

Immediate Action Plan

- Conduct a visual check: Have someone check your pupils in a dimly lit room. They should be the same size and shrink at the same rate when a light is shone in them.

- Clear the schedule: Cancel everything for the next 48 hours. No exceptions. No "just checking email."

- Monitor the neck: If you have intense stiffness or pain radiating down your arms, the impact may have affected your vertebrae, not just your brain.

- Hydrate and eat clean: Avoid alcohol and caffeine. Both mess with the brain's delicate blood flow during the recovery window.

- Consult a specialist: If symptoms like dizziness or light sensitivity last more than 10 days, look for a concussion clinic that offers vestibular therapy. Standard GPs are great, but specialists have the tools to test your eye-tracking and balance in ways a general exam won't.