Ever looked at a map of Africa and noticed that massive, blue "U-turn" right in the center? That’s the Congo. But honestly, seeing the Congo River on the map as just a wiggly line is like looking at a stick figure and thinking you know what a human looks like. It’s huge. It’s deep. And frankly, it’s a bit terrifying once you dig into the data.

Most people think of the Nile as the "big" African river. Sure, the Nile is longer. But the Congo? It’s the heavyweight champion of volume. We are talking about a river that discharges roughly 1.5 million cubic feet of water into the Atlantic every single second. To put that in perspective, if you stood at its mouth at Banana, DRC, you’d be watching enough water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool pass you by 15 times every heartbeat.

✨ Don't miss: Spanish Town Half Moon Bay CA: What Most People Get Wrong About This Quirky Coastside Landmark

Locating the Congo River on the Map: The Great Arc

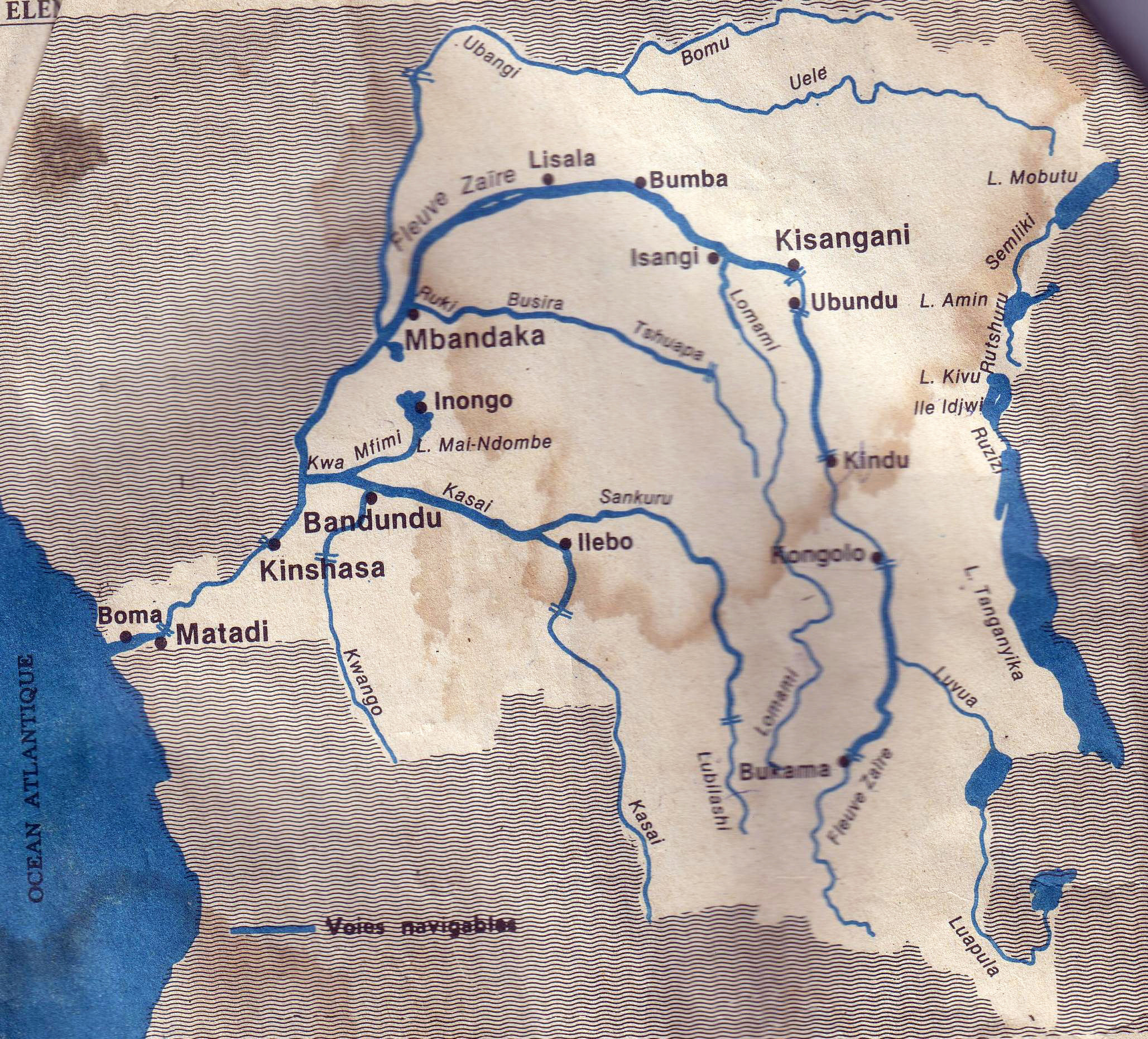

If you’re trying to find the Congo River on the map, don't just look for one spot. It’s a journey that spans nearly 3,000 miles. It starts way down in the highlands of northeastern Zambia. Back then, it’s just the Chambeshi River. Then it hits the Lualaba in the DRC and starts its famous northward climb.

It crosses the equator. Then it gets bored and crosses it again. It’s the only major river on Earth to do that.

The "Bowl" of Africa

Geographers call the area the Congo Basin, but you can basically think of it as a giant, shallow saucer. The center, known as the Cuvette Centrale, is a massive depression filled with some of the thickest rainforest on the planet. If you’re tracing the river’s path, you’ll see it creates a natural border between the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

It’s also where you find the world's closest pair of capital cities: Kinshasa and Brazzaville. They stare at each other across a four-kilometer stretch called Malebo Pool. No bridge connects them. You want to go across? You take a boat. Or you don't go.

The Deepest Secret Nobody Talks About

Here is a fact that usually blows people's minds: the Congo is the deepest river in the world. We aren’t talking about "can’t touch the bottom" deep. We’re talking about "a skyscraper could fit inside" deep.

In the lower reaches, particularly between Kinshasa and the coast, the river plunges to depths of 720 feet (220 meters). It is so dark down there that light literally can’t reach the bottom. Because of this extreme depth and the wild currents, evolution has gone a bit crazy. Scientists have found "blind" fish species down there that have evolved with shrunken eyes and pale skin because they live in a permanent midnight.

Navigation: A Map of Obstacles

You’d think a river this big would be a highway for ships. Well, it is and it isn't.

If you look at the Congo River on the map near the coast, you’ll see a series of jagged sections called the Livingstone Falls. These aren’t just "falls"; they are 220 miles of violent rapids and cataracts. They make it impossible to sail from the Atlantic Ocean directly into the heart of Africa.

- The Ocean Gap: Ships can get as far as Matadi.

- The Dead Zone: From Matadi to Kinshasa, the rapids destroy anything that tries to float.

- The Inland Highway: Once you get past Kinshasa, the river opens up again, providing thousands of miles of navigable water all the way to Kisangani.

Basically, the river is a giant puzzle. You have to offload cargo onto trains to bypass the rapids, then put it back on boats. It’s expensive, it’s slow, and it’s why Central Africa’s economy is so uniquely tied to its geography.

✨ Don't miss: Real de Catorce: What Most People Get Wrong About Mexico’s Famous Ghost Town

The Power Potential of 2026

As of early 2026, the world is still looking at the Inga Falls—a specific spot on the lower Congo—as the "Holy Grail" of renewable energy. If the "Grand Inga" dam project ever fully launches (and there’s a lot of skepticism about the $80 billion price tag), it could theoretically power half of the African continent.

But it’s a double-edged sword. The World Bank reported in late 2025 that the Congo Basin forests are worth trillions in "ecosystem services"—meaning they regulate the global climate and keep the planet breathing. Building massive dams and transmission lines means cutting into that forest. It’s a messy, complicated trade-off between green energy and preserving the world's second-largest carbon sink.

Real-World Dangers and the Human Element

Mapping the river isn't just about lines; it’s about the people on it. Just recently, in January 2026, another tragic shipwreck occurred near Mbandaka. These "baleinières" (basically large wooden boats) are often the only way for people to move goods like cassava, coffee, and timber.

The river is a lifeline, but it’s a dangerous one. Overloading is common. Navigation at night is officially banned but happens anyway. When you look at the Congo River on the map, remember that those blue lines represent the only "road" millions of people have.

How to Actually "See" the Congo Today

If you want to understand this river better, don't just stare at a static Google Map. Use these actionable steps to get a real sense of its scale:

💡 You might also like: Coordinates for Nashville TN: Why Your GPS Might Be Lying to You

- Check Satellite Feeds: Use tools like Sentinel-Hub to see the "river plume." The Congo is so powerful that its fresh water pushes miles out into the Atlantic Ocean, changing the color of the sea.

- Monitor the Peatlands: Look at the area between the Congo and Ubangi rivers. This is the world's largest tropical peatland complex. It stores more carbon than the entire world's fossil fuel emissions for three years. If it dries out or gets mapped for oil, we’re all in trouble.

- Track the "Cuvette Centrale": Use topographic maps to see the "saucer" shape. You’ll notice how every single tributary from as far away as Angola and the CAR eventually gets sucked into this one central point.

The Congo River is a force of nature that defies simple mapping. It’s a deep, dark, powerful artery that keeps the heart of Africa beating while simultaneously presenting some of the most difficult engineering challenges on the planet.

For your next step in understanding this region, look into the specific topography of the Livingstone Falls. Understanding why this 220-mile stretch of water prevents a direct connection between the Atlantic and the interior will explain more about Central African history and economics than any textbook ever could. It’s the literal bottleneck of a continent.