Language is a mess. It’s a beautiful, chaotic, inconsistent disaster zone where rules exist mostly to be broken by people who just want to express that very specific, itchy feeling of being annoyed by someone they actually like. We’re constantly hunting for cool words in the English language because the standard "happy," "sad," or "angry" just doesn't cut it when you're trying to describe the specific vibe of a rainy Tuesday in a coffee shop.

Words are tools. Some are hammers, but the ones we really love are the delicate little tweezers that pick up a sentiment no other language can quite grab.

Honestly, English is a linguistic scavenger hunt. We’ve spent centuries stealing bits and pieces from High German, Norman French, Latin, and whatever else was lying around after a war or a trade deal. That’s why we have synonyms that don't actually mean the same thing. It's why "ghost" feels different than "specter," even though they’re pointing at the same spooky guy in the hallway.

The Phonaesthetics of Why Some Words Just Sound Better

Have you ever heard of the word "cellar door"? J.R.R. Tolkien, the guy who basically invented modern fantasy, once famously noted that "cellar door" is objectively beautiful. He wasn't talking about the actual door to a basement. He was talking about phonaesthetics—the study of the pleasantness (or unpleasantness) associated with the sound of certain words.

It’s about the mouthfeel.

Some words feel like silk; others feel like gravel. Take susurrus. It’s a fancy way of saying a whispering or rustling sound. When you say it out loud, your tongue barely touches your teeth. It mimics the very thing it describes. That’s onomatopoeia’s sophisticated older cousin.

Then you’ve got words like mellifluous. It literally translates to "flowing like honey." It’s used to describe voices or music that are smooth and sweet. Compare that to a word like pulchritude. It means beauty, but it sounds like a respiratory infection. It’s a "cool" word because it’s a linguistic trap—it sounds ugly but represents the divine. That kind of irony is exactly why English stays interesting.

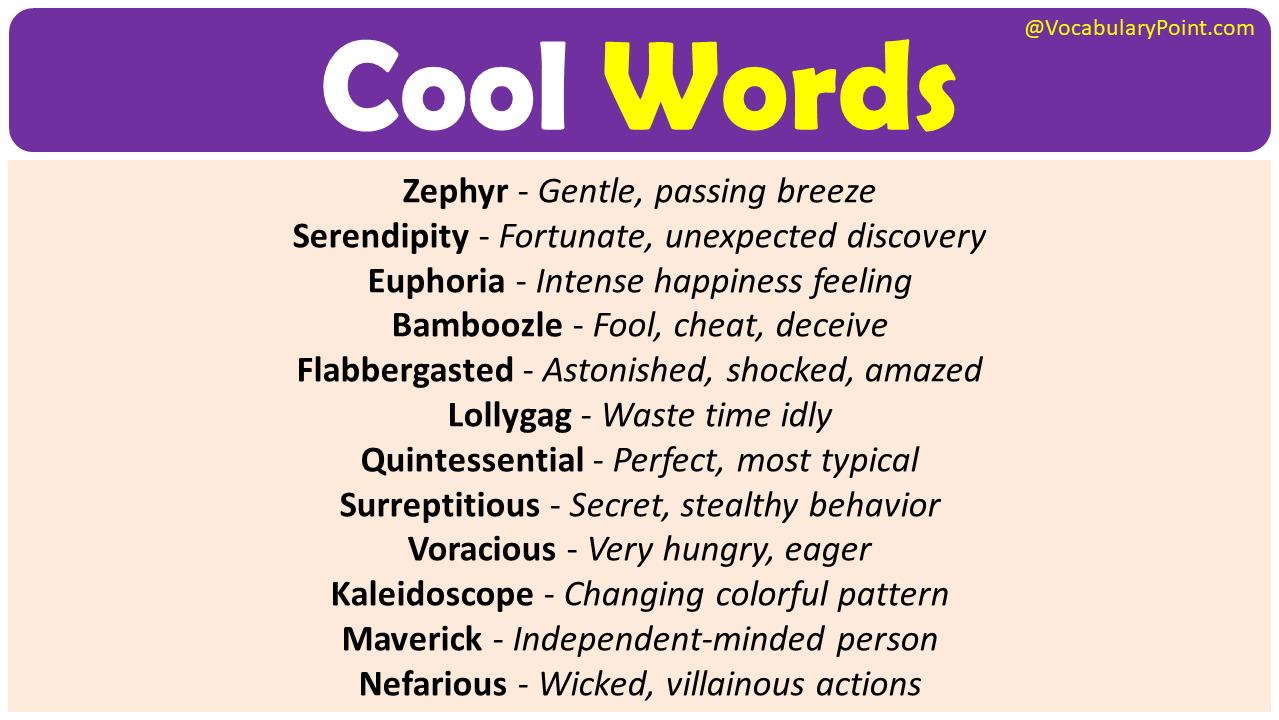

Cool Words in the English Language You Probably Aren’t Using Yet

We need to talk about petrichor. If you spend any time on the "aesthetic" side of the internet, you’ve seen it. It’s that earthy scent produced when rain falls on dry soil. It wasn't even a word until 1964, when two Australian researchers, Isabel Bear and Dick Thomas, coined it for a paper in Nature. They realized we didn't have a specific name for that "rain smell," so they mashed together the Greek petra (stone) and ichor (the fluid that flows in the veins of the gods).

That is peak cool.

Then there’s defenestration. This is a crowd favorite for a reason. It means the act of throwing someone out of a window. It sounds so formal and bureaucratic, but the actual meaning is violent and specific. It rose to fame during the Defenestration of Prague in 1618, which—believe it or not—helped trigger the Thirty Years' War. People were so annoyed they just started tossing officials out of windows. We kept the word because, honestly, sometimes you just need a very specific noun for a very specific exit strategy.

- Sonder: The realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own. (Technically coined by John Koenig for The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, but it’s entered the common lexicon because we desperately needed it).

- Ethereal: Extremely delicate and light in a way that seems too perfect for this world.

- Hiraeth: Okay, this one is Welsh, but English speakers have effectively colonized it because we don't have a word for a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return, or a home that never was.

Why Do We Keep Making Up New Ones?

Slang is just "cool words" in their larval stage.

🔗 Read more: Converting 3800 yen in dollars: What You’re Actually Buying in Japan Right Now

Think about how "cool" itself became a word for "good." In the 19th century, it just meant not hot. Then jazz culture in the 1940s took it, turned it into an ethos of detached excellence, and now it’s so foundational we don't even think about it.

We’re seeing this happen right now with internet slang. Words like goblin mode—which Oxford Languages named its 2022 Word of the Year—describe a specific type of unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy behavior that "slovenly" or "lazy" doesn't quite capture. It's a rejection of the "hustle culture" aesthetic.

We invent these because the old words get tired. They lose their punch. When everyone is "excited," nobody is truly excited. But if you're ebullient, you're practically bubbling over with energy. The nuance matters.

The Science of Linguistic "Coolness"

Researchers at the University of Warwick actually did a study once on what makes words "funny" or "appealing." They found that certain letter combinations, like "k" sounds (think "duck" or "quack") trigger a specific part of our brain that finds things more memorable or humorous.

But "cool" is different from "funny." A cool word usually offers economy of expression.

Why say "the sound of the wind in the trees" when you can say psithurism? Why say "I’m pretending to be working while actually doing nothing" when you can say cyberloafing? (That’s a real term used in organizational psychology, by the way).

The best words are the ones that act as a shorthand for a complex human emotion. Take lacuna. It’s a gap or a missing part, usually in a manuscript or a piece of writing. But we use it metaphorically for the gaps in our memories or the holes in our lives. It’s much more evocative than just saying "a blank spot."

The "Forgotten" Cool Words

There are thousands of words gathering dust in the Oxford English Dictionary that deserve a comeback.

- Apricity: The warmth of the sun in winter. You know that feeling when it’s 30 degrees out but you’re sitting in a sunbeam and for a second, you’re actually warm? That’s apricity.

- Crapulence: No, it’s not what you think. It’s the sick feeling you get after eating or drinking too much. It’s a much more dignified way to describe a hangover.

- Fudgel: An 18th-century term for pretending to work while actually doing nothing. We’ve been "fudgeling" since the dawn of the office.

How to Actually Use These Without Looking Like a Dictionary

Here is the thing: if you drop sesquipedalian (which means a person who uses long words) into a casual conversation at a bar, you’re going to look like a jerk.

✨ Don't miss: Celtic Knot Tattoo Designs: Why Your Ink Might Mean Something Else Entirely

The trick to using cool words in the English language is context. You use them when the simpler word fails. Use "shimmer" for a lake, but use iridescent for a soap bubble or a beetle’s wing. The specificity is what makes it cool, not the complexity.

Language is a social contract. If you use a word no one understands, you haven't communicated; you've just performed. But if you use a word like liminal to describe that weird, spooky feeling of an empty airport at 3 AM, people will get it. They’ll feel the word.

Stop Overthinking It

The most "cool" words are often the ones that feel inevitable once you hear them. They bridge the gap between what we feel and what we can say.

Whether it's the ephemeral nature of a sunset or the balter (to dance artlessly, without particular grace or skill, but usually with enjoyment) of a toddler, these words give us a better grip on reality.

Next Steps for Your Vocabulary:

- Audit your adjectives: Next time you go to write "very [word]," stop. Look for a single, more "cool" word that captures the intensity without the modifier. Instead of "very tired," try enervated.

- Read outside your niche: Technical manuals, 19th-century poetry, and urban slang dictionaries are all gold mines for words that haven't been overused into oblivion.

- Focus on precision: Pick one "word of the week" that describes a feeling you have often but usually struggle to name. Practice using it in your head before you say it out loud.

- Check the etymology: Knowing that tragedy comes from the Greek word for "goat song" won't make you a better person, but it will make you appreciate the weird, jagged history of the sounds coming out of your mouth.