You’re standing in the middle of a dense Vietnamese jungle, sweat stinging your eyes, and your guide points to a pile of dead leaves. "There," he says. You look. Nothing. Just dirt and foliage. Then he kicks the leaves away to reveal a tiny wooden hatch, barely the size of a pizza box. This is the entrance to the Cu Chi Tunnels Vietnam, and honestly, it’s the moment you realize everything you thought you knew about "underground warfare" is probably wrong.

Most people think of these as just narrow holes in the ground. They weren't. They were cities.

Spanning over 250 kilometers (about 155 miles) from the outskirts of Saigon all the way to the Cambodian border, this wasn't just a hiding spot. It was a massive, multi-level ecosystem. We're talking hospitals, schools, kitchens, and even theaters where performers would put on shows to keep morale high while B-52 bombers literally shook the earth above them.

The engineering "magic" of the red clay

How did these things not cave in? If you tried to dig a 200-km tunnel in most places, the first heavy rain would turn it into a tomb. But the Cu Chi district sits on a specific type of laterite clay. It’s weird stuff. When you first dig it, it’s relatively soft and manageable. But once it hits the air and dries out? It becomes hard as concrete.

The Viet Cong didn't have heavy machinery. They had hoes and baskets. They dug in the monsoon season when the earth was soft, and as the dry season rolled in, the tunnels baked into permanent, iron-rich structures. They were so strong that tanks could roll over them without the roof collapsing.

Three levels of survival

The tunnels weren't just one long pipe. They were structured in layers, almost like a basement for your basement:

- First Level (3 meters deep): Mostly for fighting, firing posts, and quick retreats.

- Second Level (6 meters deep): This is where people lived. Kitchens, sleeping quarters, and medical bays were tucked away here.

- Third Level (10-12 meters deep): The "safe zone." This was deep enough to survive direct hits from American artillery and most aerial bombings.

If you visit today, you’ll notice the air is... surprisingly okay? That's because of the termite mounds. Engineers would build fake termite mounds on the surface with small, hidden holes that acted as ventilation shafts. They’d even sprinkle pepper or stolen American uniforms around the vents to confuse the "tunnel dogs" sent to sniff them out.

Ben Dinh vs. Ben Duoc: Don't pick the wrong one

If you book a standard tour from Ho Chi Minh City, 90% of the time they’ll take you to Ben Dinh. Is it bad? No. But it is "touristified." The tunnels there have been widened so that Western frames can actually fit through them. It’s crowded, loud, and can feel a bit like a theme park.

If you want the real deal, you have to go to Ben Duoc.

📖 Related: The Spotted Cow Cafe: Why This Toowoomba Icon Actually Lives Up to the Hype

It’s about 30 minutes further away, which keeps the massive bus crowds at bay. The tunnels here are closer to their original size (though still slightly widened for safety). It feels eerily quiet. You get to see the Memorial Temple, and the history feels a lot heavier when you aren't elbowing twenty other people for a photo of a trapdoor.

Honestly, if you're claustrophobic, Ben Dinh is probably your only choice. But if you want to feel that "black echo" the soldiers talked about, Ben Duoc is the winner.

What it was actually like down there

It wasn't heroic. It was miserable.

Half of the soldiers at any given time had malaria. 100% of them had intestinal parasites. You weren't just sharing space with your comrades; you were sharing it with scorpions, centipedes, and fire ants. In the 1991 documentary The Cu Chi Tunnels, survivors talked about how they’d stay underground for weeks at a time during heavy "carpet bombing" campaigns.

They ate mostly boiled cassava dipped in salted peanuts. You can actually try this at the end of the tour. It’s surprisingly filling, but imagine eating nothing else for three years while living in total darkness.

The "Tunnel Rats"

We can't talk about the Cu Chi Tunnels Vietnam without mentioning the men who had to go in after the Viet Cong. These were the "Tunnel Rats"—mostly American, Australian, and New Zealander soldiers who were small enough to fit. They’d go down with nothing but a .45 pistol and a flashlight.

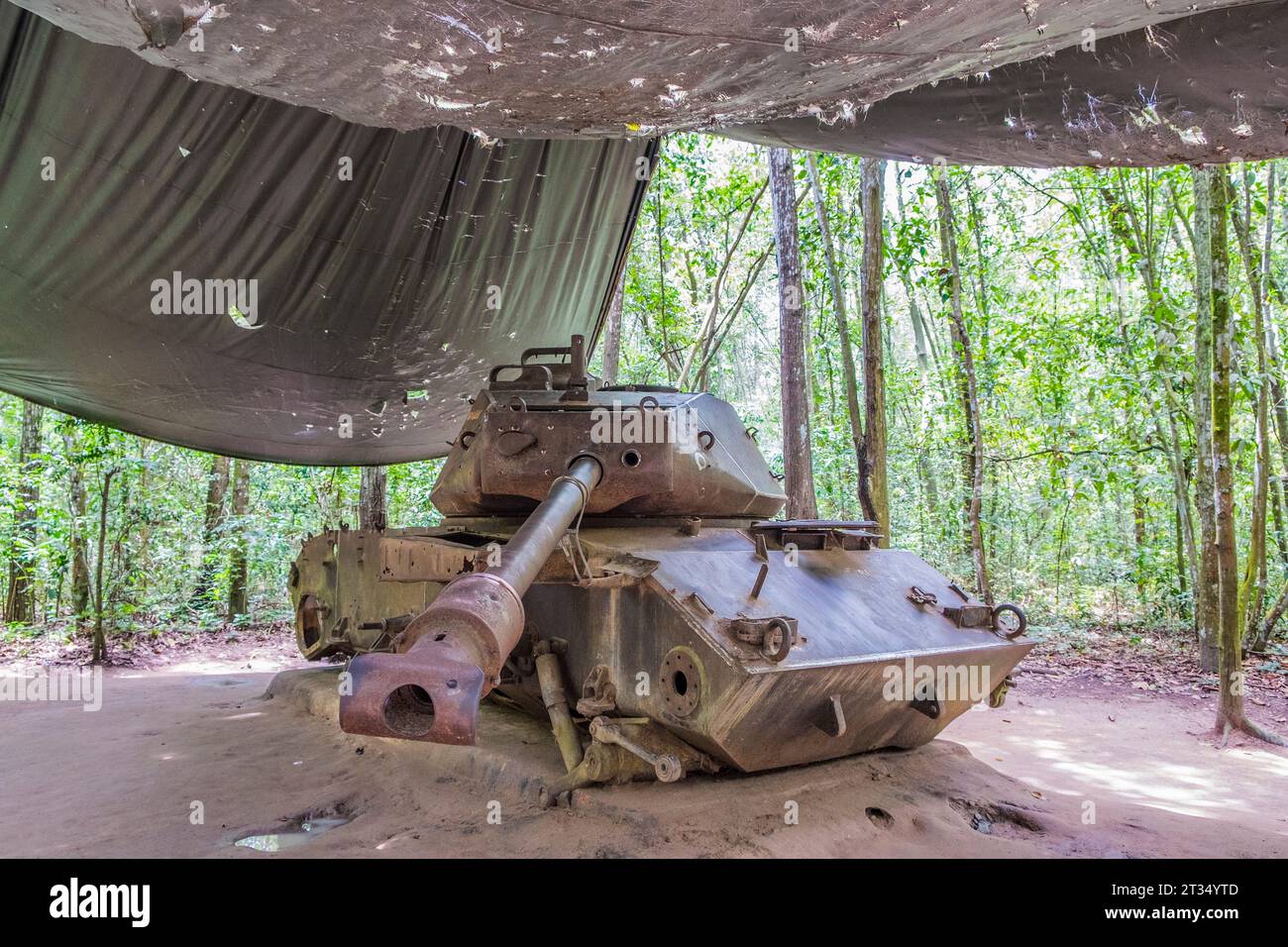

It was a game of high-stakes hide-and-seek where the "seeker" usually lost. The tunnels were rigged with "booby traps" like the "see-saw" or "clipping armpit" traps—basically sharpened bamboo stakes (punji sticks) often smeared with waste to cause infection.

Modern visitor tips for 2026

If you're planning a trip this year, here’s the ground truth on how to do it right:

- Go Early: Most tours leave HCMC at 8:00 AM. If you can hire a private driver and leave at 7:00 AM, you’ll beat the heat and the crowds.

- The Shooting Range: Yes, you can fire an AK-47 or an M16. It costs around 600,000 VND (~$25 USD) for 10 bullets. It is incredibly loud. If you’re looking for a somber, historical experience, maybe skip this part—it’s a bit jarring to hear gunfire while looking at a memorial.

- Clothing: Wear clothes you don't mind getting red clay on. It stains. Also, bring bug spray. The mosquitoes in the Cu Chi jungle don't care that the war is over; they are still looking for targets.

- Physicality: If you have back issues, don't go into the tunnels. Even the widened ones require you to "duck-walk" for long stretches. It’s a workout.

The bigger picture

The tunnels are a testament to "total war." It wasn't just soldiers fighting; it was entire villages moving underground to survive. Today, they stand as a "Special National Historical Site."

For some, it's a place of immense pride and "revolutionary heroism." For others, especially veterans from the other side, it's a place of ghosts. Understanding that nuance is what makes the visit worth it. It’s not just a tourist attraction; it’s a scar on the landscape that tells a story of unbelievable human endurance.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Book the Ben Duoc site instead of Ben Dinh if you have the extra 2 hours to spare; it’s five times larger and significantly more authentic.

- Check the weather. Avoid going right after a massive downpour in the rainy season (May to October), as the forest floor becomes a slippery red mess.

- Hire a private guide who specializes in military history rather than a general "city tour" guide to get the deeper technical details on the trap designs and ventilation systems.