You walk into a boardroom in Tokyo. You’ve got the best product on the market. The price is right. Your presentation is sleek. You finish, wait for the applause, and get... silence. A polite nod. Maybe a vague "we will consider this." You leave thinking you nailed it.

You didn't.

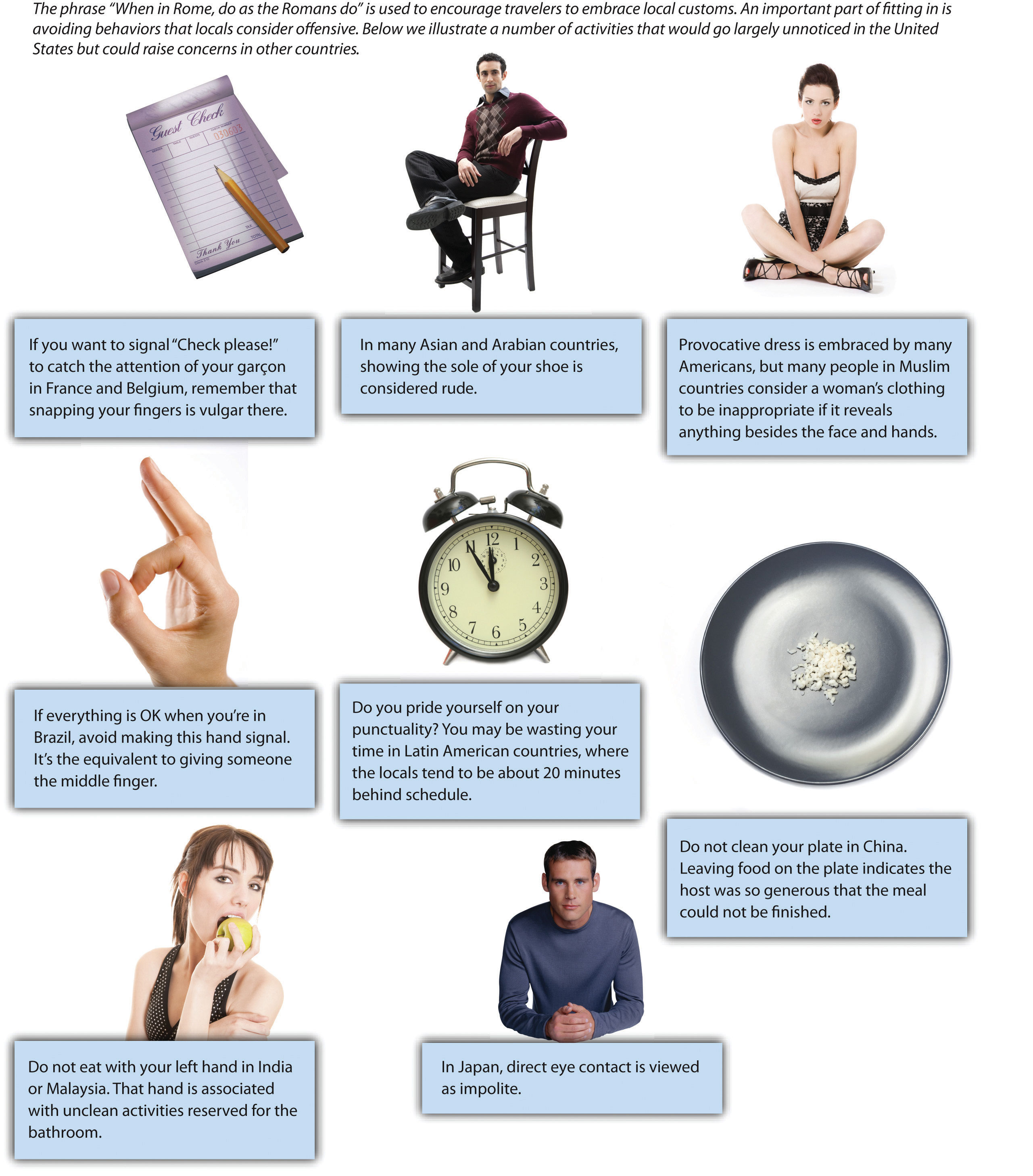

Actually, you probably tanked the deal five minutes in without saying a word. This is the reality of cultural differences in business. It isn't just about knowing which hand to shake or how to hand over a business card. It’s about the invisible scripts running in the back of everyone’s head. Honestly, most people think a globalized world means we all think the same way now. We don't.

In fact, the more "connected" we get, the more these friction points rub raw. If you're looking for a checklist of "don'ts," you're looking at it the wrong way. It’s about the "why."

The High-Context Trap

Most Americans or Australians are "low-context" communicators. Basically, if we want something, we say it. "I disagree with that point" is a standard Tuesday afternoon. But in high-context cultures—think Japan, Korea, or Saudi Arabia—the message is rarely in the words. It’s in the air.

Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD and author of The Culture Map, breaks this down brilliantly. In a high-context environment, criticizing a colleague in front of their peers isn't just "giving feedback." It’s a social execution. You’ve made them lose face. Once that happens, the business relationship is essentially dead.

I’ve seen deals in Dubai fall apart not because of the numbers, but because a junior associate interrupted a senior VP. In the West, we call that "proactive." In the Middle East, it can be seen as a massive lack of adab (etiquette).

The silence in that Tokyo boardroom? That was the message. In Japan, "yes" often just means "I hear you speaking," not "I agree to the contract." If you can't read the room, you're flying blind.

Timing Isn't Just a Clock Thing

Let's talk about the "Swiss Watch" vs. "Island Time" myth. It’s more complex than just being late.

There’s a concept called Monochronic vs. Polychronic time.

- Monochronic (Germany, Switzerland, USA): Time is a commodity. We "spend" it. We "waste" it. One thing at a time. If the meeting is at 2:00 PM, 2:05 PM is an insult.

- Polychronic (Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Middle East): Time is fluid. Relationships matter more than the schedule. If a friend walks into the office while I’m in a meeting with you, I might talk to both of you at once. It’s not rude; it’s a priority shift toward the human element.

If you’re a German manager running a team in Brazil, and you start every meeting by barking about the 9:00 AM start time, you’re going to have a revolt. Not because they’re lazy. But because you’re acting like a robot instead of a person. You haven't asked about their families. You haven't built the rapport. In many cultures, the "work" doesn't start until the "relationship" is solid.

The Myth of Flat Hierarchies

Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands love flat hierarchies. They basically treat the CEO like a slightly more experienced colleague. You can challenge them. You can tell them their idea is rubbish.

Try that in China or India.

💡 You might also like: M\&T Bank Stock Price Today: Why Most Investors Are Missing the Big Picture

Power Distance is a real metric. In high Power Distance cultures, the boss is the boss. Period. If you try to implement a "democratic" decision-making process in a Nigerian firm, the employees might actually lose respect for you. They expect the leader to lead. Asking for their "input" can sometimes be interpreted as "I don't know what I'm doing."

It’s a weird paradox. You think you're being inclusive, but you’re actually signaling incompetence.

Negotiating the "No"

Westerners—especially Americans—are obsessed with getting to "Yes." We want the signature. We want the win.

But in many cultures, the word "No" is considered harsh and vulgar. In Indonesia, there are supposedly twelve different ways to say "yes" that actually mean "no."

- "It is difficult." (No)

- "We will see." (Probably no)

- "I will check with my supervisor." (Definitely no)

If you keep pushing for a clear answer, you’re seen as aggressive and unrefined. You’re missing the subtle cues. On the flip side, some cultures are incredibly blunt. A Dutch partner might tell you your marketing plan is "illogical and poorly researched." They aren't trying to be mean. They’re being "honest." If you’re from a "face-saving" culture, you’ll take that personally and quit. If you’re Dutch, you’ll expect a counter-argument and a beer afterward.

Real World Stakes: The Walmart in Germany Disaster

This isn't just academic. Remember when Walmart tried to move into Germany in the late 90s? It was a disaster. Why? Because of cultural differences in business that they completely ignored.

First, they tried to make German clerks smile at customers. In Germany, a random stranger smiling at you intensely while you buy milk is... suspicious. It’s not "friendly"; it’s weird.

Then there was the "Walmart Cheer." Employees were expected to chant "W-A-L-M-A-R-T!" before shifts. To many Germans, this felt uncomfortably like cult-like behavior or forced labor rallies. They hated it.

Walmart also tried to ban employees from dating each other—a common US corporate policy. A German court basically laughed them out of the room, stating that such a rule violated basic human rights. They lost hundreds of millions of dollars because they thought "Business is Business." It isn't. Business is Culture.

✨ Don't miss: Chris LaRocca Network Connex: What Most People Get Wrong About the Infrastructure Titan

Logic vs. Emotion in Persuasion

How do you convince someone?

In the US, we love "Applications-first" logic. We want the "How-to" and the "Results." Show me the case study! Give me the ROI!

In France or Spain, "Principles-first" logic often wins. They want to know the theory behind the strategy. If the underlying philosophy isn't sound, they don't care about your case study. You have to build the intellectual framework before you present the solution. If you skip the "Why," you look shallow.

Practical Steps for Navigating Cultural Friction

Stop assuming "common sense" exists. Common sense is just a collection of cultural biases you picked up by age ten.

- Audit your own "Context" level. Are you a "say it like it is" person? Realize that half the world thinks you're a bully. Are you a "read between the lines" person? Realize the other half thinks you're being shifty.

- Research the "Power Distance" of your target market. If you're heading to a high power-distance country, send someone with a title that matches the person they are meeting. Sending a "Sales Associate" to meet a "Managing Director" is an insult in many places.

- The "Three-Second Rule" for Silence. In Western conversations, silence is a gap that needs to be filled. In many Asian cultures, silence is a sign of respect and reflection. If you ask a question and they don't answer immediately, do not keep talking. If you interrupt their silence, you are interrupting their thought process.

- Watch the "Direct Negative Feedback." If you're working with a team from Southeast Asia or Latin America, never give individual criticism in a group setting. Do it one-on-one, and wrap it in plenty of positive context.

- Learn the "Social Contract." In places like Russia or Mexico, you might spend three hours at lunch talking about history, family, and football before a single word of business is mentioned. This isn't "wasted time." This is the most important part of the deal. They are deciding if they trust you, not your company.

The goal isn't to become an expert in every culture. That's impossible. The goal is to be cognizant. When things feel "weird" or "frustrating," stop. Don't label the other person as "slow" or "rude." Ask yourself: "What cultural script are they following that I don't know yet?"

That's where the profit is.