Light is weird. We think we see it, but we’re mostly seeing how it bounces off stuff. When you sit down to start a day and night drawing, the biggest hurdle isn't your hand-eye coordination or your expensive charcoal set; it's your brain lying to you about what color the sky actually is. You think the day is yellow and the night is blue. It's rarely that simple. Honestly, if you want to capture the transition of time on a single page, you have to stop drawing "things" and start drawing the way photons behave at 2:00 PM versus 2:00 AM.

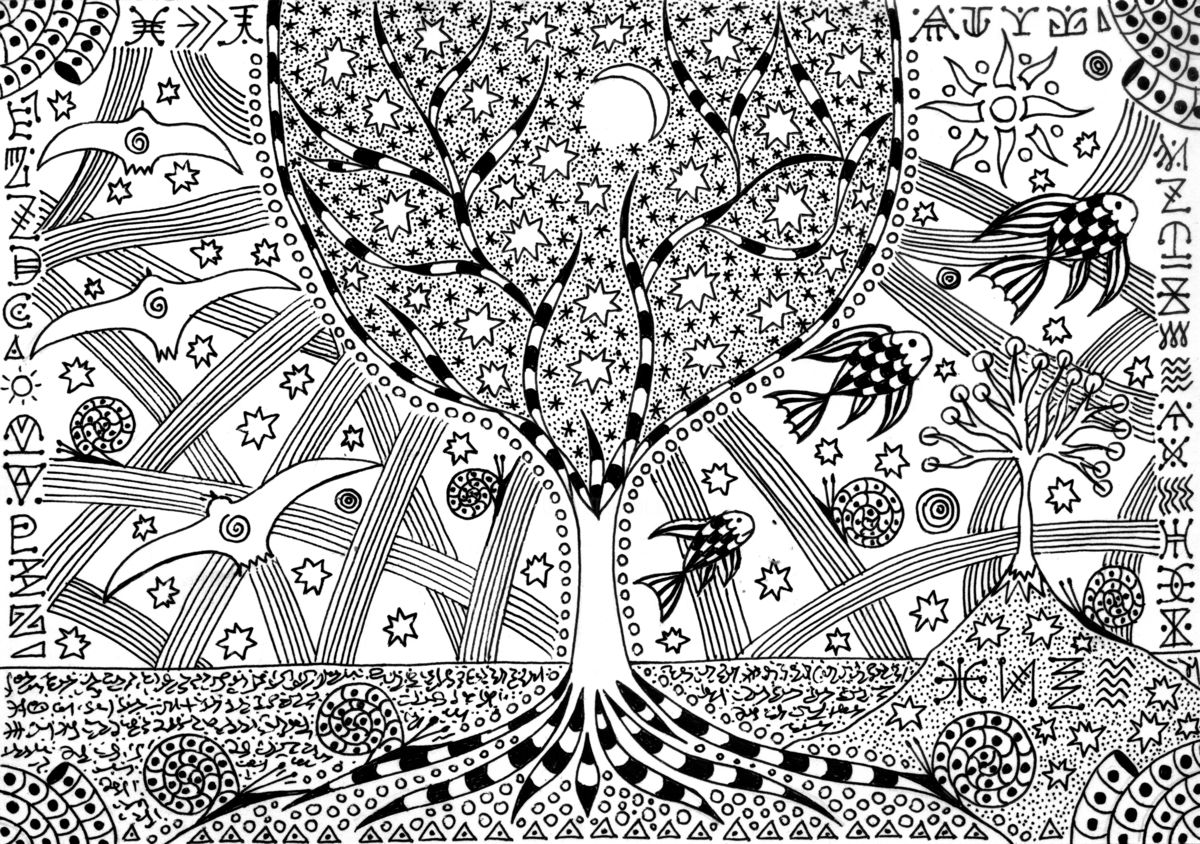

Most beginners fall into the trap of just using a black pencil for the "night" side and a yellow one for the "day" side. That looks like a coloring book. Real art—the kind that makes people stop scrolling on Instagram—requires an understanding of the Kelvin scale and how our eyes' rods and cones switch jobs when the sun dips below the horizon.

The science of why your day and night drawing looks "fake"

The atmosphere is a giant filter. During the day, Rayleigh scattering makes the sky blue because shorter wavelengths hit gas molecules and scatter everywhere. When you're working on the "day" portion of your piece, you aren't just drawing a sun; you're drawing a giant, blue light bulb that wraps around every object. This is why shadows in the daytime aren't black. They're often a deep, desaturated violet or blue. If you paint a tree in the sun and make the shadows pitch black, it looks like a hole in the universe. It looks wrong.

Night is different. It’s not just "dark day."

📖 Related: Neutral rugs for bedroom: What most designers get wrong about "boring" colors

Our eyes shift from photopic vision to scotopic vision. We lose the ability to see color well in low light. This is called the Purkinje effect. Ever notice how red flowers look almost black at night, but blue flowers seem to glow? That’s biological. When you’re crafting a day and night drawing, the night side should have shifted color values. If you keep the same saturation levels in your night scene as your day scene, you lose the atmosphere. You lose the "vibe."

Splitting the canvas without making it look like a middle school project

How do you actually merge these two worlds? Some people do a hard line down the middle. That's fine if you're going for a graphic, minimalist look. But if you want something more evocative, try a gradient or a "shattered" transition.

Imagine a city street. On the left, the sun is hitting the bricks, bringing out the warm oranges and ochres. As your eye moves right, the shadows stretch. They don't just get longer; they get cooler. By the time you reach the right edge of the paper, the streetlamps are the only light source. This creates a narrative. It tells a story of a day ending. You've basically compressed twelve hours into twelve inches of paper.

James Gurney, the guy who wrote Color and Light, talks extensively about how "local color" (the actual color of an object) is almost irrelevant compared to the light hitting it. A white car isn't white at noon; it's a reflection of the blue sky and the yellow sun. At night, under a sodium-vapor streetlamp, that same car is an ugly, muddy orange.

Shadows are where the magic happens

Stop using black. Please.

Unless you are doing high-contrast ink work, black is a killer of depth. In a daytime scene, your shadows should be influenced by the sky. In a nighttime scene, they are influenced by ambient light—the moon, neon signs, or even the "skyglow" of a nearby city.

- For daytime: Mix your primary color with its complement to get a rich shadow.

- For nighttime: Use deep indigos, burnt umbers, and maybe a touch of Alizarin crimson for those warm, dark areas.

It's about contrast. In the day, the contrast is sharp. The transition from light to shadow is often a crisp line. At night, light "blooms." Think about how a car's headlights look in the dark—there’s a hazy glow around the source. Replicating that bloom is the secret sauce for a realistic night aesthetic.

Master the "Blue Hour" transition

There's this tiny window of time called the Blue Hour. It happens just after the sun goes down but before it’s fully dark. This is the "sweet spot" for any day and night drawing because it acts as the perfect bridge. The sky is a deep, electric blue, and the orange lights of the city start to pop.

Why does this look so good? Complementary colors. Blue and orange are opposites on the color wheel. When you put them next to each other, they vibrate. If your drawing feels flat, it’s probably because your color palette is too "safe." Throw some aggressive oranges into the windows of your night scene and watch the whole thing wake up.

I've seen so many artists struggle because they try to draw every leaf on a tree in the dark. You can't see those leaves. If you can't see them in real life, don't draw them. Night drawing is about "suggestion." You draw the shapes that the light hits, and you let the viewer's brain fill in the rest. It's a psychological game. You're giving the audience just enough information to understand it's a tree, and then letting the darkness do the heavy lifting.

Common pitfalls in dual-lighting compositions

One thing people mess up constantly is the moon. The moon is not a light source in the same way the sun is. It’s a rock. It reflects sunlight. Moonlight is actually quite dim, and it’s technically slightly "redder" than sunlight, even though our brains perceive it as blue or silver due to the way our eyes work in the dark.

If you make your moon as bright as your sun, the "night" side of your drawing just looks like a cloudy day.

Another mistake: ignoring the temperature of artificial light. Not all light bulbs are created equal. LED lights are often cool and clinical. Old incandescent bulbs are warm and cozy. If you're drawing a scene with a house, the light spilling out of the windows should feel warm—like a refuge from the cold, blue night outside. This creates emotional resonance.

Actionable steps for your next piece

Start small. Don't try to draw an entire metropolis. Pick a single object—a mailbox, a tree, a parked car.

- Study the "Terminator" line: This is the line where light turns into shadow. On a round object, this line is soft. On a cube, it's hard. Notice how this line changes as the light source moves from overhead (day) to the side (sunset) to non-existent (night).

- Use a limited palette: Try doing a day and night drawing using only four colors. Maybe a warm yellow, a deep blue, a red, and white. Forcing yourself to mix colors teaches you more about light than a 100-pack of markers ever will.

- Observe real life at 5:00 PM: Go outside. Look at a white wall. It isn't white. It’s probably a weird shade of peach or lavender. Take a photo, then turn the saturation up on your phone. You’ll see colors you didn't notice before. Use those colors in your art.

- Focus on value over hue: If your values (how light or dark something is) are correct, you can use almost any color and it will still look "right." A green sun and a purple sky can look realistic if the light levels are consistent.

The most successful drawings of this type aren't just technical exercises; they capture the feeling of time passing. They make the viewer feel the heat of the afternoon and the chill of the evening. That doesn't come from a specific pencil brand. It comes from looking at the world, really looking at it, and realizing that shadows are never just black and the sky is never just blue.

Work on your transitions. Soften your edges where the light fades. Use the "glow" effect for your night lights by layering light strokes of a bright color over a darker base. Practice drawing the same scene at three different times of day to see how the shapes "flatten" or "deepen" based on where the sun sits. This builds the muscle memory you need to tackle a complex split-scene composition without getting overwhelmed.