You’re looking at a screen. Maybe it’s a checkout page, or maybe it’s a genome sequence on a lab report. Something looks off. It isn't exactly like the one you saw yesterday, but it’s close enough to recognize. That tiny gap? That’s it. In the simplest terms, the definition of a variation refers to a version of something that differs in some way from a benchmark, a standard, or a previous iteration.

It’s the "almost-the-same" factor.

Context matters more than the dictionary here. If you’re a baker, a variation is adding sea salt to a chocolate chip cookie. If you’re a statistician, it’s the spread of data points around a mean. Honestly, the word is a shapeshifter. It behaves differently depending on who is holding the clipboard.

✨ Don't miss: Why 1185 Avenue of the Americas Still Dominates the Midtown Skyline

The Statistical Reality of Variation

In the world of data, variation isn't just a "change." It's the heartbeat of uncertainty.

Statistics experts like those at the American Society for Quality (ASQ) break this down into two very distinct buckets: common cause and special cause. Common cause variation is the noise. It’s the inherent, predictable fluctuations in a process. Think about your morning commute. It takes 20 minutes on Monday and 22 minutes on Tuesday. Nothing "happened"—it’s just life.

Then you have special cause variation. This is the outlier. This is the 50-minute commute because a truck flipped over on the interstate. When we look at the definition of a variation in a business process, we are usually trying to hunt down these special causes to eliminate them.

Variance is the mathematical cousin here. To get technical, variance measures how far each number in a set is from the mean. If you want to see how much your sales figures are swinging month to month, you calculate the variance. It tells you if your business is a steady ship or a wild rollercoaster.

High variation usually equals high risk. Low variation equals boring, predictable success. Most CEOs prefer boring.

Genetic Variation and the Blueprint of Life

Biology takes the definition of a variation and turns it into a survival mechanism. Without it, we’re all clones, and one nasty virus wipes out the species.

Genetic variation refers to the differences in DNA sequences among individuals within a population. These mutations—some good, some neutral, many irrelevant—are what allow for natural selection. It’s how we get different eye colors, blood types, and, more importantly, different immune responses.

Consider the work of the National Human Genome Research Institute. They track "variants," which are just locations in the genome where people differ. Sometimes it’s a single "letter" change in the DNA code (a SNP, or Single Nucleotide Polymorphism).

It’s wild to think that a single variation in a gene like MC1R is the reason some people have red hair while others don't. One tiny shift in a sequence of billions. That is the power of a biological variation. It isn't a mistake; it's a feature of evolution.

Variation in Music and Art

Let’s pivot.

Music. You’ve heard "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star," right? Mozart famously took that simple melody and wrote "Twelve Variations on 'Ah vous dirai-je, Maman'."

In this creative context, the definition of a variation is the act of taking a theme and altering it through rhythm, harmony, or counterpoint while keeping the original "soul" of the piece intact. The listener should still recognize the ghost of the original tune.

Jazz is basically Variation: The Genre. A musician takes a standard—a known melody—and spends ten minutes spinning variations on it through improvisation. They change the "what" while honoring the "where."

- Rhythmic displacement (shifting the beat).

- Melodic inversion (flipping the tune upside down).

- Harmonic substitution (using different chords).

It’s all variation. It’s all change within a framework.

Product Variations in E-commerce

If you’ve ever bought a t-shirt on Amazon, you’ve interacted with the commercial definition of a variation.

In retail, a variation (often called a "parent-child" relationship) allows a single product to exist in different colors, sizes, or materials without needing separate pages for every single one. The "Parent" is the idea of the shirt. The "Child" is the Medium Blue Crewneck.

Why does this matter for SEO and user experience?

Because if you treat every color as a completely separate product, you dilute your search authority. By grouping variations, you concentrate all your reviews and traffic onto one high-performing page.

👉 See also: Surana Solar Limited Share Price: What Most People Get Wrong

But be careful. In the world of Shopify or Amazon, a "variation" has strict rules. You can’t list a t-shirt and then make a "variation" that is actually a pair of socks just to piggyback on the reviews. That’s "variation abuse," and it’ll get your account banned faster than you can say "algorithm."

The Legal and Contractual Angle

Lawyers look at variation through the lens of the "Variation Clause."

In a contract, a variation is a formal change to the scope of work or the terms of the agreement. Construction is the biggest playground for this. You start building a house, and halfway through, you decide you want a sunroom instead of a patio.

That requires a "Variation Order" (or Change Order).

It’s a legal acknowledgement that the original "standard" has been altered. This is where things get messy. Who pays for the extra labor? Does it extend the deadline? Without a clear definition of a variation in the initial contract, these changes lead to lawsuits.

Real-world tip: Always define how a variation is approved. If it’s not in writing, it didn't happen.

Misconceptions: Variation vs. Variable

People mix these up constantly.

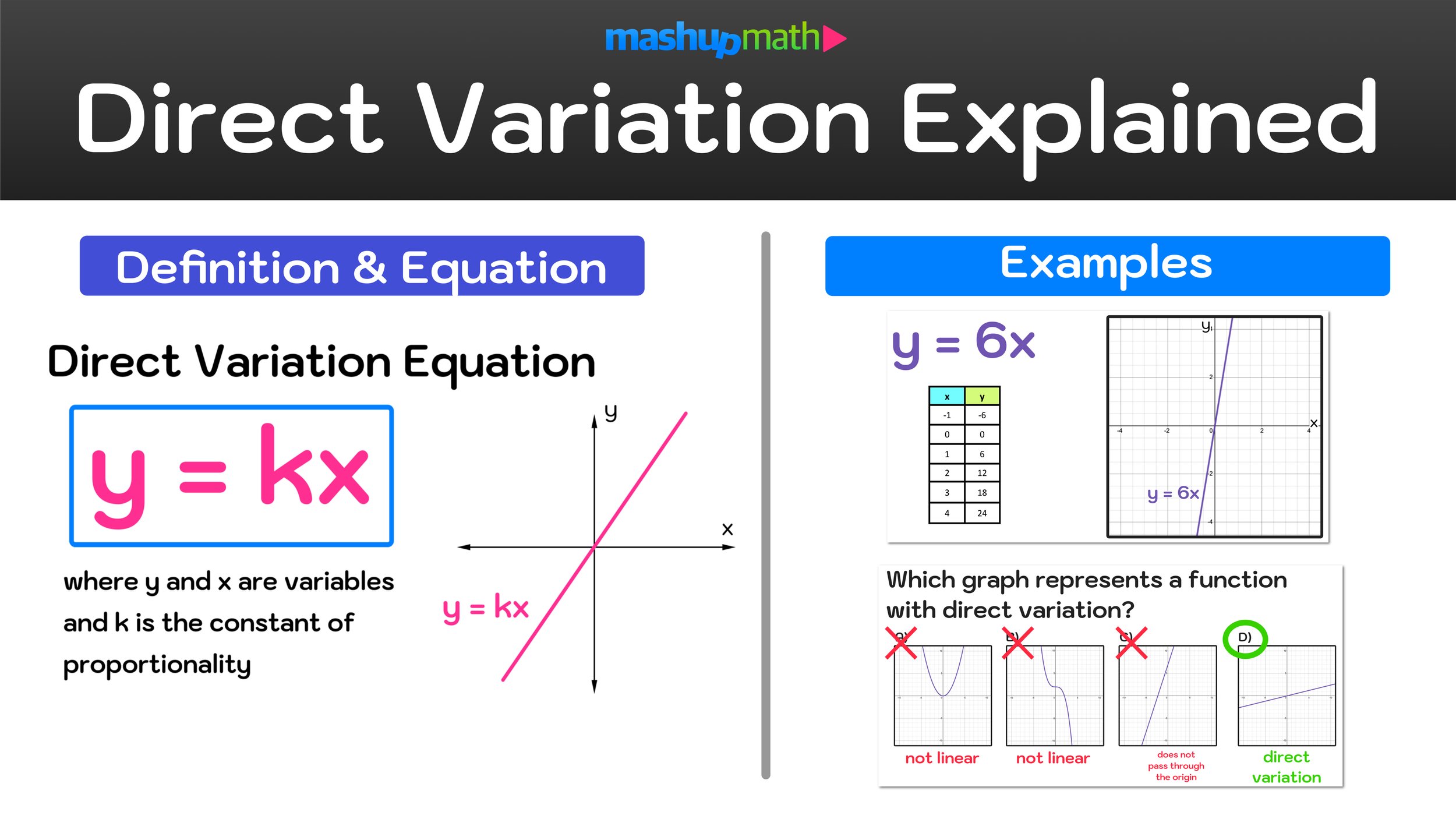

A variable is a symbol or a placeholder (like $x$ in an equation). It represents a value that can change.

A variation is the actual act or result of that change.

If the variable is "Temperature," the variation is the fact that it’s 72 degrees today and 75 degrees tomorrow. The variable is the category; the variation is the deviation within that category.

Don't use them interchangeably if you’re writing a technical report. You’ll look like an amateur.

Why We Crave (and Fear) Variation

Psychologically, humans are weird about this.

We love "variety"—which is just a collection of variations. It’s the spice of life. But in our systems, we crave "consistency."

Six Sigma, a set of techniques for process improvement popularized by Motorola and GE, is obsessed with reducing variation. The goal is to reach a level where 99.99966% of products are defect-free. That means virtually zero variation from the standard.

Why? Because variation costs money.

If every iPhone came out a slightly different size, no case would fit. If every Big Mac tasted different, the brand would collapse. We want the variation in our entertainment, our fashion, and our art. We want zero variation in our brakes, our medicine, and our technology.

Actionable Steps for Managing Variation

Whether you are managing a team, coding an app, or just trying to understand a scientific paper, handling variation requires a strategy.

1. Identify the Baseline

You can't have a variation without a standard. Define what "normal" looks like first. If you don't have a documented process, everything is a variation, which is just chaos in disguise.

2. Measure the Spread

Don't just look at the average. The average depth of a river might be four feet, but if one part is ten feet deep, you’re still going to drown. Look at the range. Look at the standard deviation.

✨ Don't miss: Sponsored by Bud Light: Why These Two Words Sparked a Marketing Revolution

3. Determine the "Why"

Is the change intentional? In A/B testing (a marketing variation), the change is the point. You want to see if Version B performs better. If it’s a manufacturing glitch, the change is a failure.

4. Document the Change

In business and law, an undocumented variation is a liability. Use change logs. Use version control (like Git for developers). Ensure that anyone looking at the "child" can find their way back to the "parent."

5. Embrace Necessary Deviations

In creative fields, stop trying to be perfect. The "mistakes"—the variations from the plan—are often where the innovation happens. Post-it Notes were a variation of a failed adhesive. Penicillin was a variation in a "clean" lab culture.

Variation is simply the delta between what we expected and what we got. Sometimes that delta is a bug. Sometimes it’s the next big breakthrough.

Stop viewing it as an error. Start viewing it as data.