You’re standing in an empty concrete shell of a building, and you’ve got a dream of serving the best cacio e pepe in the city. But right now, all you have is a floor that needs plumbing and a vision. Most people think the menu is the hardest part of opening a restaurant, but honestly? It’s the commercial kitchen floor plan. If you mess up the flow between the walk-in and the prep station, your line cooks are going to spend half their shift playing dodgeball with each other. That’s how burns happen, orders get backed up, and your labor costs skyrocket because you need three people to do the job of two.

Efficiency isn't just a buzzword. It's the difference between a Friday night that feels like a well-oiled machine and one that feels like a sinking ship.

Why Your Commercial Kitchen Floor Plan Dictates Your Profit

Space is money. In the world of commercial real estate, every square foot you give to the kitchen is a square foot you aren't selling to a customer in the dining room. You've got to be stingy but smart. If you cram everything in, your staff will be miserable. If you make it too sprawling, they'll be exhausted.

The goal of a solid commercial kitchen floor plan is to minimize steps. You want your sauté chef to be able to reach the refrigeration, the range, and the plating area without taking more than a couple of strides. It’s about ergonomics. It's about physics. It’s about not having the guy with the 50-pound pot of boiling pasta water crossing paths with the server carrying a tray of crystal wine glasses.

The Assembly Line Myth

A lot of people think every kitchen should look like a McDonald’s from the 1950s. The "Assembly Line" layout is great if you’re doing high-volume, repetitive tasks—think pizzas, sandwiches, or tacos. It’s a straight shot. Prep, cook, plate, go. But if you’re running a fine-dining establishment with a 12-course tasting menu, an assembly line is a nightmare. You need a "Zone" system.

In a zone-style commercial kitchen floor plan, you group activities. You have a dishwashing zone (keep it near the entrance where servers drop off dirty plates), a cold prep zone, a frying zone, and a plating zone. It keeps the chaos contained. You don't want the heat from the grill messing with your pastry chef’s delicate chocolate work. Heat mapping is a real thing, and ignoring it is a fast way to ruin your inventory.

📖 Related: How Much Is One Bit Coin Worth Today: The Price Nobody Expected

The Regulatory Headache (That You Can't Ignore)

Before you even think about where the shiny new Vulcan range goes, you have to talk about the unsexy stuff: building codes and health department regulations. I’ve seen restaurateurs buy $50,000 worth of equipment only to realize their floor plan doesn't meet the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements for aisle width.

Your local health department usually requires specific "flow" to prevent cross-contamination. Generally, this means dirty dishes shouldn't travel through clean food prep areas. Your grease trap location isn't just a suggestion; it’s usually dictated by the existing plumbing lines in the slab. Moving those lines costs a fortune. Sometimes, the building literally tells you what your floor plan has to be. You just have to listen.

The Ergonimics of the "Work Triangle"

Residential architects talk about the triangle between the fridge, the stove, and the sink. In a professional setting, we call it the "Work Flow."

- Receiving: Where the truck drops off the crates of tomatoes.

- Storage: Dry goods, walk-in coolers, and freezers.

- Prep: Where the knife work happens.

- Cooking: The heart of the beast.

- Service: Where the food meets the heat lamps and the servers.

- Cleaning: The pit.

If these don't follow a logical sequence, you’re dead in the water. Imagine receiving a shipment of frozen fish and having to carry it through the entire cooking line just to get to the freezer. It’s inefficient and, frankly, kind of gross.

Island vs. Zone: Which One Wins?

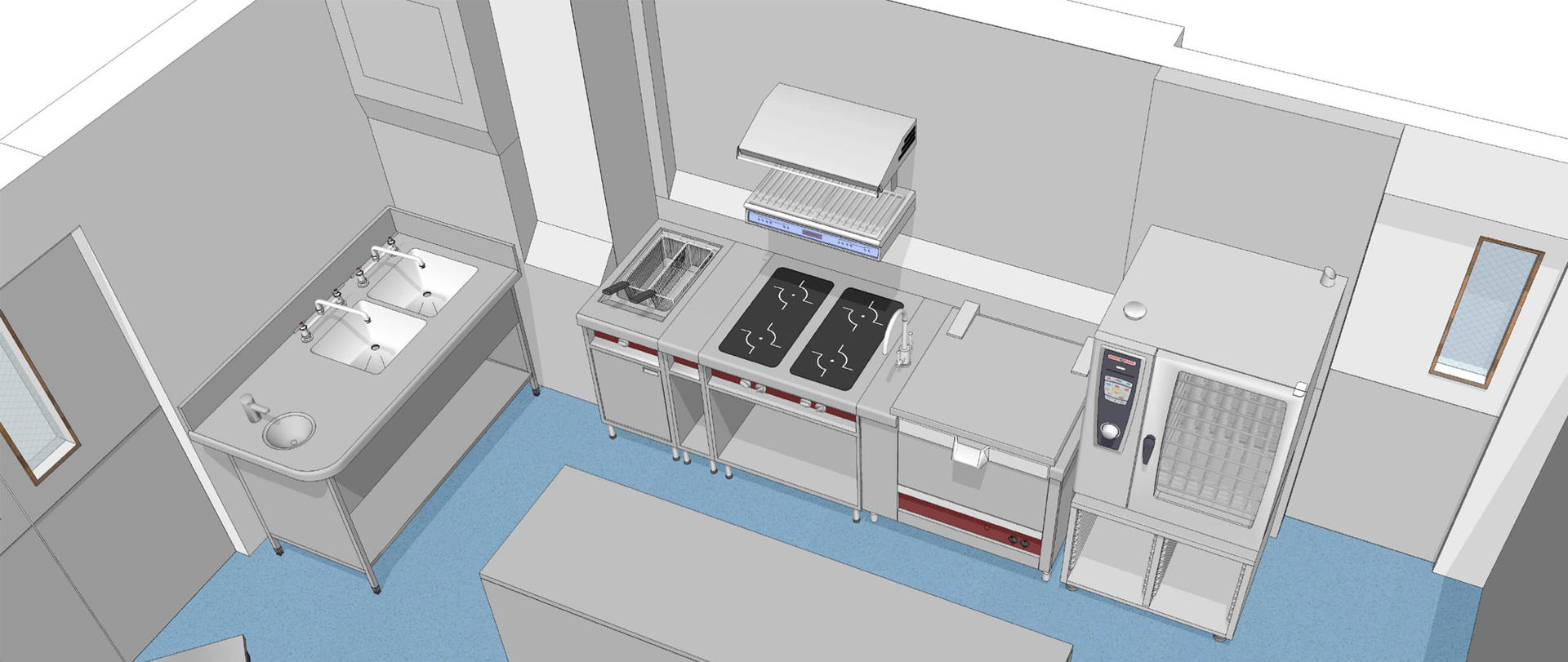

The "Island" layout is the darling of many high-end chefs. You put the main cooking equipment—the ranges, grills, and fryers—right in the middle of the room. This creates a central hub. The "perimeter" of the room is used for prep and storage. It promotes communication because everyone is facing each other. It feels like a stage.

However, an island requires a massive hood system. And hoods are expensive. Like, "sell your firstborn" expensive. A wall-mounted hood is significantly cheaper because you're only venting one side. If you're on a tight budget, the "Zone" or "Ergonomic" layout against the walls is usually the way to go.

The Ventilation Trap

Speaking of hoods, let's talk about Make-Up Air (MUA). When you suck all that hot, greasy air out of a kitchen, you’re creating a vacuum. If you don’t bring fresh air back in, your front door will be impossible to open, and your dining room will smell like old fry oil.

A lot of DIY floor plans forget to account for the physical space that MUA units and ductwork take up. They aren't just on the roof; they need vertical shafts. If you don't account for this in your commercial kitchen floor plan, you'll end up with a weird bump-out in the middle of your prep station that wasn't in the drawings. It happens all the time.

Small Spaces, Big Problems

Ghost kitchens are all the rage right now. They’re tiny. We’re talking 200 to 400 square feet. In a space that small, you have to go vertical. Shelving is your best friend. But be careful—if you put things too high, you’re looking at worker's comp claims from people falling off step stools.

In small footprints, multi-functional equipment is king. Why have a separate steamer and a convection oven when you can buy a Combi-oven? It takes up half the space and does twice the work. It’s more expensive upfront, but when you’re paying $50 per square foot in rent, it pays for itself in six months.

Maintenance and the "Cleanability" Factor

Health inspectors love stainless steel. They hate nooks and crannies. When you’re laying out your floor plan, think about how someone is going to mop behind the equipment.

Can the equipment slide out? Are the gas lines on quick-disconnect hoses? If you wedge a heavy range into a corner where no one can reach the wall behind it, you’re inviting a grease fire or a pest infestation. Neither is good for business. Give yourself at least six inches of "slop" room. It’ll make your deep-clean nights a lot less miserable.

Putting It Into Practice: Real Steps

Don't just start drawing lines on a piece of paper. You need to be methodical.

📖 Related: PST to Indian Time: Why Most People Get the Math Wrong

- Get an "As-Built" Survey: Know exactly where your columns, drains, and electrical panels are. Don't guess.

- Define Your Menu First: You can't design a kitchen if you don't know what you're cooking. A sushi bar needs very different plumbing than a burger joint.

- Draft the Flow: Use arrows to trace the path of a single ingredient from the back door to the customer's plate. If the arrows look like a bowl of spaghetti, your plan is bad.

- The 3D Walkthrough: Use software or even just tape on the floor. Physically walk the space. Mimic the motion of sautéing and then turning to plate. Does your elbow hit a wall? If so, fix it now.

- Consult the Pros: Fire suppression guys and HVAC contractors should see your plan before it's finalized. They will find the "impossible" spots that an architect might miss.

Designing a commercial kitchen floor plan is a puzzle where the pieces can catch on fire. Take your time. Spend the money on a good consultant or a seasoned kitchen designer. It’s a lot cheaper to move a sink on a computer screen than it is to jackhammer it out of a finished floor because it was three inches too far to the left.

Get your plumbing and gas lines stubbed in correctly the first time. Verify your aisle widths for ADA compliance. Ensure your refrigeration isn't sitting right next to your hottest grill. If you do these things, your staff will stay longer, your food will come out faster, and you might actually enjoy running your restaurant.