History isn't always clean. Sometimes, it’s buried under a parking lot in Virginia, tucked away between an interstate and a train station. If you’ve ever walked through the Shockoe Bottom neighborhood in Richmond, you’ve stood near the Devil’s Half Acre. It sounds like a ghost story, doesn’t it? But for thousands of people in the 19th century, the horror was very, very real.

Robert Lumpkin didn’t care about ghosts. He cared about margins.

Lumpkin was a slave trader who bought a small plot of land in Richmond in the 1840s. He turned it into a complex that became the beating heart of the domestic slave trade. This wasn't just a jail; it was a logistics hub for human misery. People called it the Devil’s Half Acre because, honestly, what else could you call a place where families were ripped apart for a quick buck?

What Actually Happened at the Devil’s Half Acre

Most people think of slavery as a purely agrarian, "Gone with the Wind" plantation fantasy. That’s a mistake. It was an industry. By the mid-1800s, Richmond was the second-largest slave-trading center in the United States, trailing only New Orleans. Lumpkin’s Jail—the official name for the Devil’s Half Acre—was where the "product" was held before being shipped "down the river."

The compound was a grim collection of four buildings. There was Lumpkin’s own residence, a guest house for visiting traders, a kitchen, and then the jail itself. The jail was a brick building, two stories high, with barred windows and a heavy dose of despair.

It’s weird to think about, but Lumpkin lived right there. He even had a family with an enslaved woman named Mary Elizabeth, whom he eventually married (or as close to marriage as the law allowed back then). This kind of complexity is what makes the Devil’s Half Acre so hard to wrap your head around. It wasn't just a dungeon; it was a home, a business, and a prison all rolled into one half-acre of Richmond soil.

The Everyday Brutality of Shockoe Bottom

If you were an enslaved person at the Devil's Half Acre, your life was basically a waiting game. You waited for the auction block. You waited for the chains.

The conditions were cramped. People were packed into rooms with little ventilation. Disease was a constant threat, though traders like Lumpkin tried to keep people "sellable," which is a clinical way of saying they wanted them to look healthy enough to fetch a high price. It was a factory setting.

Traders from all over the South would stay at Lumpkin’s guest house. They’d drink, eat, and talk shop while, just a few yards away, hundreds of people were mourning the loss of their children or parents. The juxtaposition is nauseating.

The Shocking Shift to "God's Half Acre"

Here is the part that usually trips people up. After the Civil War ended and Richmond fell in 1865, the Devil’s Half Acre underwent a transformation that sounds like something out of a movie.

Mary Elizabeth Lumpkin—Robert's widow—inherited the property. She ended up leasing the old jail to a Baptist minister named Nathaniel Colver. He wanted to start a school for formerly enslaved people.

Can you imagine?

The very rooms where people were once chained became classrooms. The place was nicknamed "God's Half Acre" during this time. This school eventually moved and grew, becoming what we now know as Virginia Union University (VUU), a prominent Historically Black University. It’s a wild bit of historical irony that one of the most oppressive sites in America birthed a temple of education and liberation.

Why We Lost the Site for Decades

For a long time, Richmond just... forgot. Or maybe it chose to forget.

Urban renewal in the 20th century was brutal to Black history. The construction of I-95 and various parking lots literally paved over the Devil’s Half Acre. By the 1980s, you could have parked your car right on top of the site and never known you were standing on one of the most significant archaeological sites in the country.

It wasn't until the early 2000s that archaeologists, led by folks like David Dutton, began excavating. They found the foundation of the jail. They found personal items—bits of pottery, nails, things that made the site feel human again. It wasn't just a story anymore; it was physical evidence.

The Controversy Over Preservation

Now, this is where things get messy today. What do you do with a site like the Devil’s Half Acre?

Some people want a massive, somber memorial. Others want a museum that explains the economics of the slave trade. Then there’s the city of Richmond, which has to balance historical preservation with the fact that Shockoe Bottom is a prime piece of real estate.

There have been heated debates about building a minor league baseball stadium in the area. Imagine cheering for a home run while sitting on a slave jail. Thankfully, that plan was mostly scrapped due to public outcry. But the tension remains. How much of our "dark history" are we willing to look at every day?

📖 Related: Why an Image of a Flame Is the Hardest Thing to Capture

Comparing the Slave Trade Sites

- Lumpkin’s Jail: Specialized in high-volume transit and temporary housing.

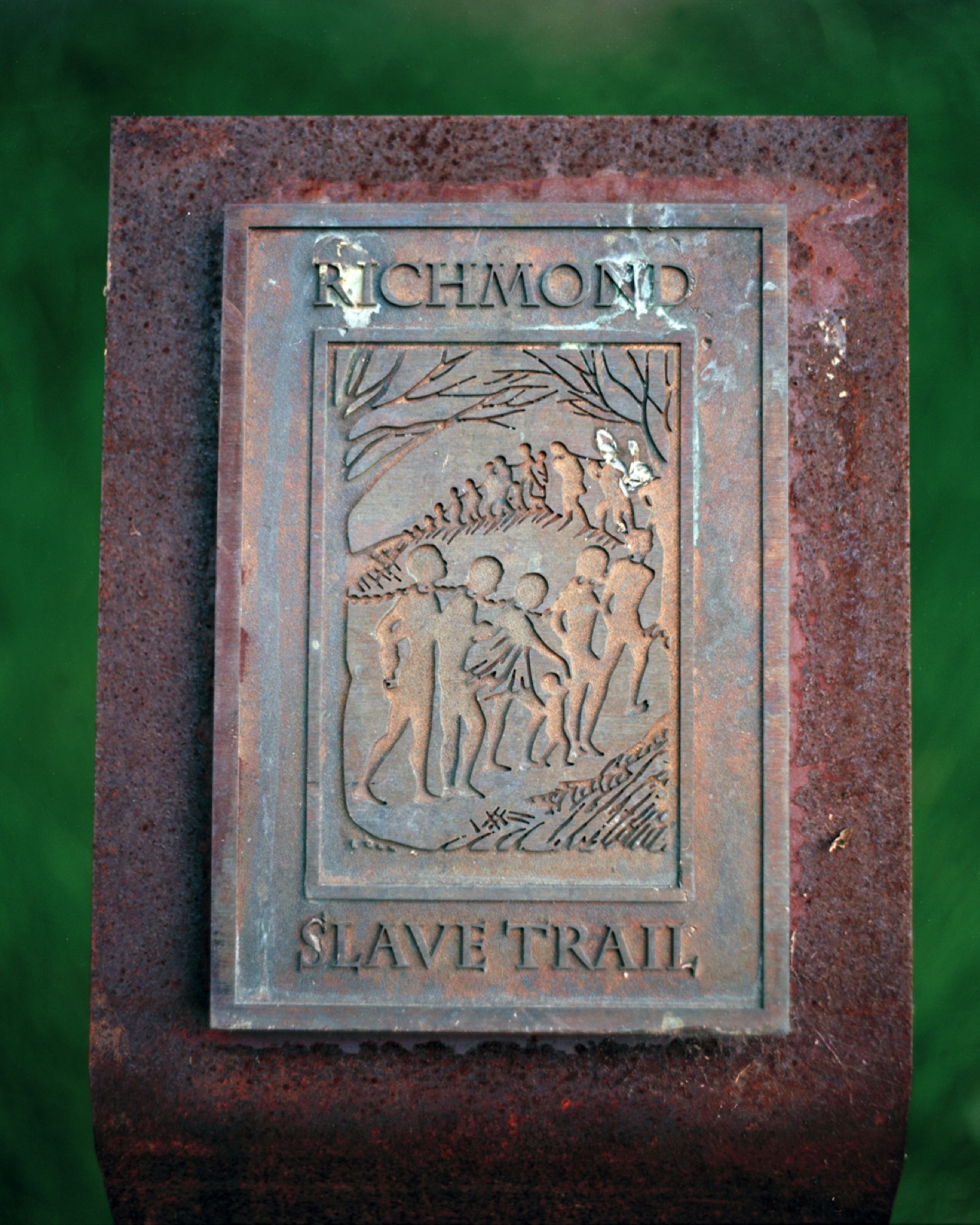

- The Slave Trail: A walking path in Richmond that connects various sites, including the Devil's Half Acre.

- Manchester Docks: Where many enslaved people first arrived in Richmond before being marched to the jails.

The Real Numbers (As Far As We Know)

Historians estimate that between 1830 and 1860, roughly 300,000 enslaved people were sent from Virginia to the Deep South. A huge chunk of those passed through Richmond. Lumpkin wasn't the only trader, but he was one of the most successful.

It’s hard to get exact numbers because records were often destroyed or weren't kept with the precision we’d like. But archaeological finds at the site—like the sheer size of the foundations—confirm that this was a high-capacity operation.

Why You Should Care About the Devil’s Half Acre Today

This isn't just about the past. It's about how we tell the story of America. If we only talk about the "great" parts, we're lying to ourselves.

The Devil’s Half Acre represents the systemic nature of slavery. It wasn't just a few "bad actors." It was an integrated part of the Richmond economy. Banks financed it. Insurance companies covered the "cargo." The city’s infrastructure was built around it.

Understanding this site helps us understand the wealth gaps and systemic issues we still see in the 2020s. It’s the "ground zero" for the American experience of race and capitalism.

How to Visit the Site Properly

If you're heading to Richmond, don't expect a theme park. It’s a solemn place.

- Start at the Richmond Slave Trail. It’s a self-guided walking tour that takes you from the docks to the jails.

- Look for the historical markers in Shockoe Bottom. The site of Lumpkin’s Jail is located near the intersection of 15th and East Franklin Streets.

- Visit the Black History Museum & Cultural Center of Virginia. They provide the context you need to understand what you’re seeing at the actual site.

- Be respectful. People died here. Families were destroyed here. It’s a graveyard of sorts, even if there aren't many headstones.

Practical Steps for History Buffs and Locals

If you want to support the preservation of sites like the Devil’s Half Acre, there are actual things you can do. It's not just about reading an article and moving on.

Support the Sacred Ground Historical Site Coalition. This group has been at the forefront of protecting the area from commercial development. They do the heavy lifting in city council meetings.

Educate yourself on the "Richmond 300" plan. This is the city's long-term development roadmap. Keep an eye on how they plan to treat Shockoe Bottom. Public comment periods are your best friend if you want to ensure history isn't paved over again.

Visit Virginia Union University. Seeing where the "God's Half Acre" legacy lives on today provides a much-needed sense of hope. It reminds you that while history is heavy, it doesn't have to be the end of the story.

The Devil’s Half Acre is a reminder that the past is always just beneath the surface. Sometimes literally. Whether we choose to dig it up or leave it buried says more about us than it does about the people who lived there 180 years ago.

Go see it for yourself. Stand in the bottomland of Richmond. Feel the weight of the air. It’s an experience that a textbook or a YouTube video just can’t replicate. Honesty about our history is the only way to build a future that isn't built on top of a jail.