Plates crash. One dives. The earth literally eats itself.

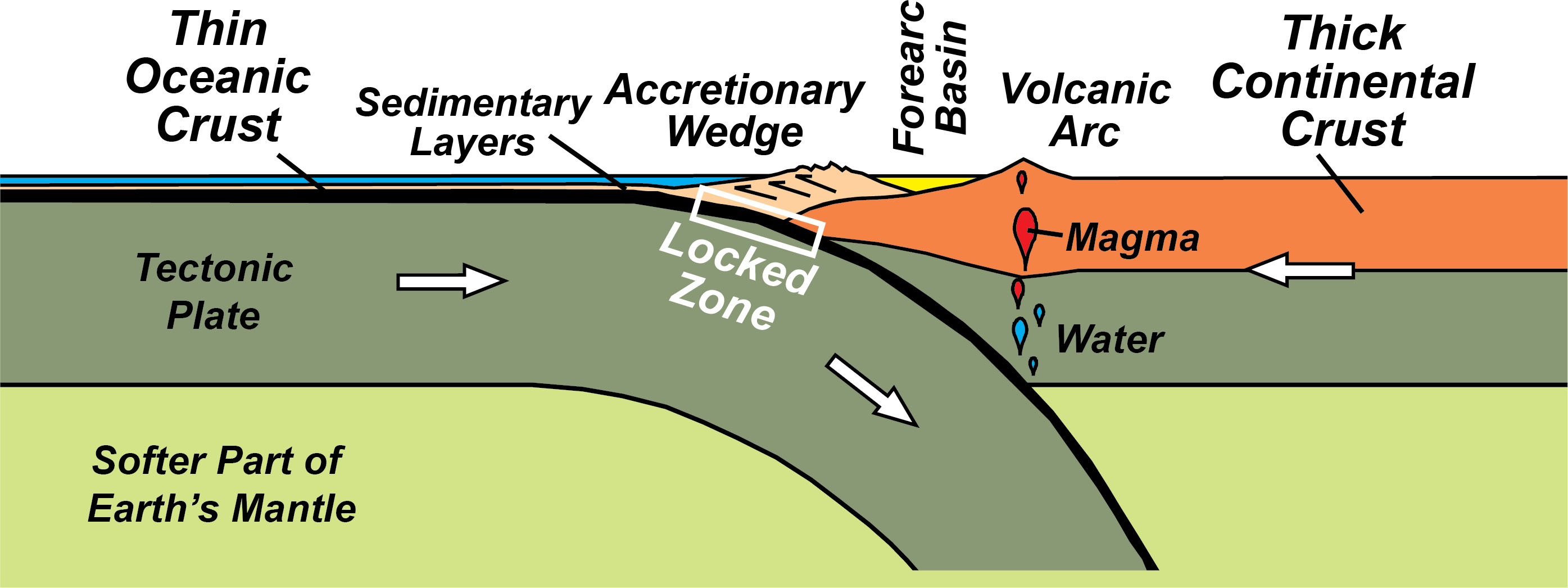

If you look at a standard diagram of subduction zone dynamics in a middle school textbook, you see two crisp lines. One plate goes down at a perfect 45-degree angle, there’s a little orange blob labeled "magma," and maybe a triangle for a volcano. It looks clean. It looks simple.

It’s also mostly a lie.

In reality, these zones are messy, hydration-dependent, chaotic graveyards of oceanic crust. They aren't just lines on a map; they are the primary engines of our planet's chemistry. Without them, Earth would be a stagnant rock like Mars. We need that recycling. But the way we visualize it often skips the most interesting—and terrifying—parts of the physics involved.

What a Diagram of Subduction Zone Actually Needs to Show

Most people think of subduction as a "collision." That's not quite right. It's more of a sinking. Oceanic lithosphere is dense. It’s cold. Because it’s spent millions of years at the bottom of the sea, it’s soaked up water like a giant, stony sponge. When it hits a lighter continental plate, it doesn’t just get pushed down; it falls.

Gravity is the real driver here. Geologists call it "slab pull."

Imagine a heavy rug sliding off a table. Once enough of the rug hangs over the edge, the weight of the hanging part pulls the rest of it down. That’s what’s happening at the Mariana Trench or the coast of Chile. If your diagram of subduction zone mechanics doesn't emphasize the weight of that "slab," it’s missing the engine.

The Role of Water (The Great Lubricant)

Here is a weird fact: Rocks don't melt just because they get hot.

Deep in the Earth, the pressure is so high that it actually keeps rock solid, even at temperatures that should melt it. To get a volcano, you need a cheat code. That code is water. As the oceanic plate descends, the intense pressure squeezes water out of the minerals. This water rises into the overlying mantle wedge.

It lowers the melting point.

💡 You might also like: Samsung Store Glendale CA: What Most People Get Wrong

Think of it like putting salt on an icy sidewalk. The ice doesn't get warmer, but it melts anyway. This process, called flux melting, is why we have the Ring of Fire. If you see a diagram of subduction zone processes where the melting starts right at the bottom of the trench, it's wrong. The melting actually happens miles away, usually when the slab reaches a depth of about 100 kilometers.

The Anatomy of the Chaos

Let’s talk about the "Accretionary Wedge." This is basically the debris pile of the planet.

As the oceanic plate slides under the continent, it acts like a giant bulldozer. It scrapes off layers of deep-sea sediment, dead plankton, and volcanic basalt. All that junk gets crammed into a messy pile at the edge of the continent.

It’s not pretty.

In a high-quality diagram of subduction zone features, you’ll see this labeled near the trench. In places like the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, you can actually walk on this stuff. It’s a jumble of rocks that used to be at the bottom of the ocean, now shoved thousands of feet into the air.

Why the Angle Matters

Not all slabs dive the same way.

In the Peru-Chile trench, the slab goes down at a very shallow angle. We call this "flat-slab subduction." Because it doesn't dive deep quickly, it rubs against the bottom of the continent for hundreds of miles. This creates massive mountains far inland—think of the Rockies.

Conversely, in the Western Pacific, slabs often dive nearly vertically. They’re old, they’re heavy, and they want to sink fast. This creates "roll-back," where the trench actually moves backward over time, stretching the crust and creating new seas.

The Megathrust Problem

We can't talk about a diagram of subduction zone without talking about the "Locked Zone."

The two plates aren't smooth. They are jagged, rocky, and incredibly stubborn. They get stuck. For decades or centuries, the plates don't move, but the pressure builds. The upper plate starts to bend and flex like a wooden ruler being pushed from the side.

Eventually, the "stick" becomes a "slip."

When the friction finally gives way, the upper plate snaps back. This is a Megathrust earthquake. This is Tohoku in 2011. This is the Cascadia Subduction Zone off the coast of Oregon and Washington. When that plate snaps back, it displaces the entire column of ocean water above it.

That's your tsunami.

Most diagrams show a little star for an earthquake, but they rarely show the "elastic rebound" of the overriding plate. Honestly, that’s the part that matters for human life. Understanding that the land you are standing on is currently being "compressed" like a spring is a very different feeling than just looking at a static map.

The Deep Carbon Cycle

There is a huge debate in the geosciences right now about how much carbon actually makes it down into the mantle.

For a long time, we thought most of the carbon trapped in shells and limestone on the seafloor just stayed down there forever. Or at least for a few billion years. Now, researchers like those involved in the Deep Carbon Observatory are finding that a lot of it "leaks" back up through volcanic gases.

Your diagram of subduction zone is actually a giant recycling bin for the atmosphere.

If the subduction process stopped, carbon would stay trapped in the crust. The planet would cool down. Alternatively, if too much leaks back out, we get a greenhouse runaway. It’s a delicate balance managed by the slowest conveyor belt in the universe.

Actionable Insights for Visualizing the Earth

If you are studying these systems or trying to create a visual representation of them, stop looking for symmetry. Nature hates it.

- Look for the "Benioff Zone": This is the plane of earthquakes that follows the sinking slab. If you plot these dots on a 3D graph, you can literally see the shape of the dead ocean floor sitting under the continent.

- Check the Volcanic Arc distance: The distance from the trench to the volcanoes tells you how steep the slab is diving. A huge gap means a shallow dive; a short gap means a steep plunge.

- Distinguish between "Oceanic-Oceanic" and "Oceanic-Continental": When two ocean plates meet, the older (denser) one loses. This creates island arcs like Japan or the Aleutians, rather than mountain ranges like the Andes.

- Watch the fluids: Always look for the arrows representing water moving from the slab into the mantle. That's the "spark" that starts the fire.

Understanding a diagram of subduction zone isn't about memorizing labels. It’s about recognizing a massive, slow-motion engine that regulates the air we breathe and the ground we walk on. It’s violent, wet, and incredibly heavy.

📖 Related: Setting up Office 365 email on iPhone: Why the Outlook App usually beats the Mail App

To truly grasp it, stop thinking of the Earth as a solid object. Think of it as a very thick, very slow liquid that occasionally breaks.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To see this in action, check out the IRIS (Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology) interactive maps. They allow you to view real-time earthquake data that traces the exact outlines of these subducting slabs. You can also research the "Cascadia Episode" of the Eocene to see how a change in subduction angle completely reshaped the North American continent.