It is the holy grail of American politics. The "balanced budget." Most people today look at the national debt—now screaming past $34 trillion—and think of the 1990s as some kind of fiscal fairy tale. You’ve probably heard it in debates or seen it on social media: "Clinton was the last guy to actually balance the books."

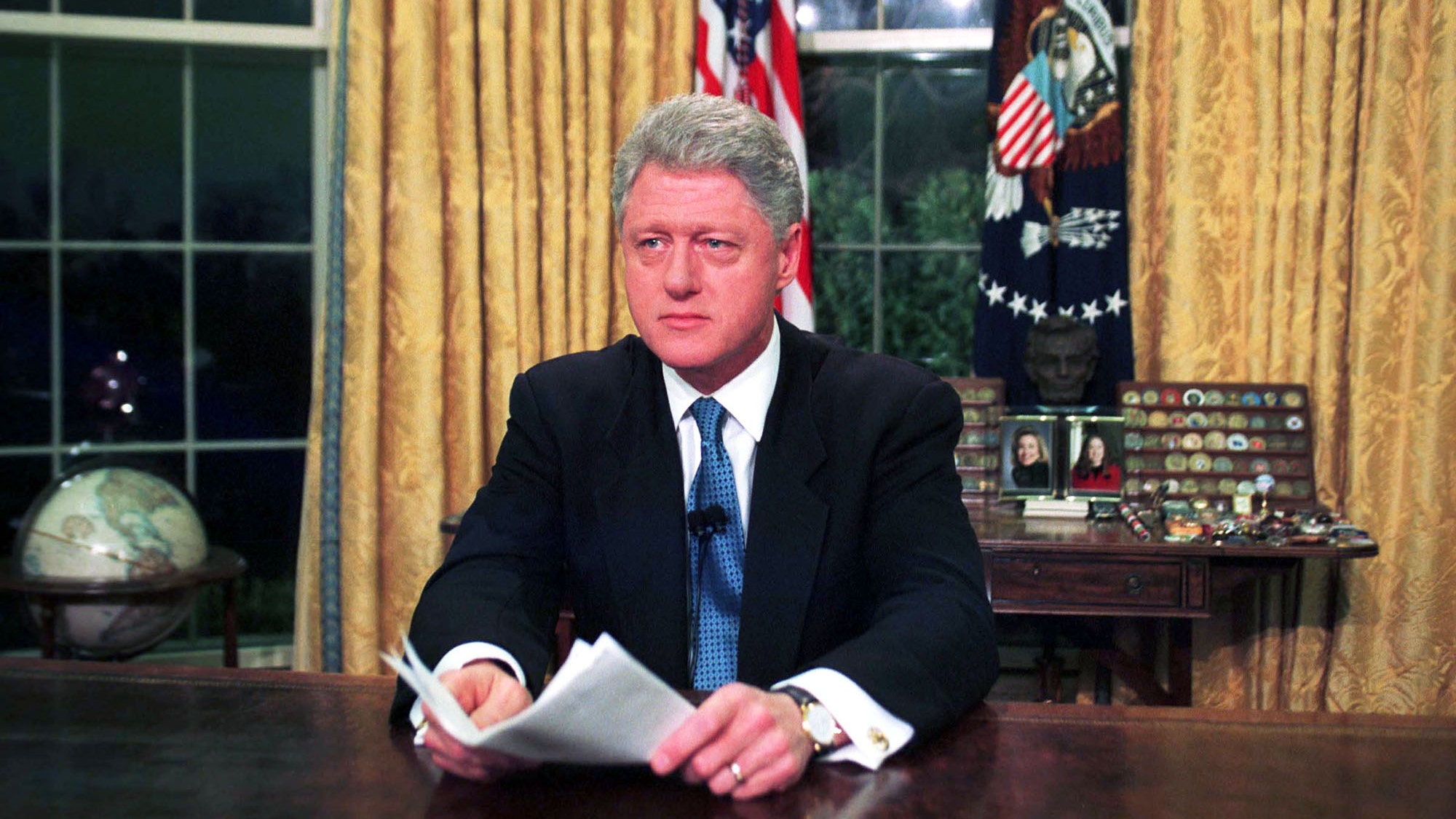

But did Bill Clinton balance the budget, or was he just the beneficiary of a once-in-a-century economic perfect storm? Honestly, the answer is a mix of both, and it depends entirely on how you define "balanced."

💡 You might also like: Saint Paul Weather Forecast: Why the Twin Cities Are So Hard to Predict

If you look at the raw numbers, the federal government recorded a unified budget surplus for four straight years: 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2001. That hadn't happened since the 1920s. In 2000 alone, the surplus hit $236 billion. That is real money. But if you start peeling back the layers of how the government accounts for Social Security, the "balanced" part gets a little more complicated.

The 1993 Gamble That Started It All

When Clinton took office in 1993, the deficit was a monster. We’re talking about $290 billion, which was roughly 4.7% of the GDP at the time. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) was basically screaming that the ship was sinking.

Clinton’s first big move was the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993. It was a massive gamble. He raised the top income tax rate from 31% to 39.6% and bumped up the corporate tax rate. He also added a 4.3-cent-per-gallon gas tax.

Republicans hated it. Newt Gingrich famously predicted it would lead to a "job-killing recession." Not a single Republican in the House or Senate voted for it. Vice President Al Gore had to cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate just to get it through.

🔗 Read more: The War on the Eastern Front: What Most People Get Wrong About the Largest Conflict in History

Instead of a recession, the economy took off like a rocket.

The Dot-Com Boom and the "Peace Dividend"

You can’t talk about the Clinton surplus without talking about the 1990s tech explosion. Basically, the world discovered the internet, and everyone went crazy.

The stock market didn't just grow; it bubbled. This created a massive windfall in capital gains taxes. People were getting rich on Pets.com and Netscape, and Uncle Sam was taking his cut. In 1993, tax revenues were about 17.0% of GDP. By 2000, they had climbed to 20.0%.

Then there was the "Peace Dividend." The Cold War had ended, and the Soviet Union was gone. This allowed the U.S. to slash defense spending. In 1993, we spent about 4.3% of our GDP on the military. By 2000, that was down to 2.9%. We weren't just making more money; we were finally spending less on tanks and planes.

Was it Really a "Surplus"?

Here is where the math gets kinda' murky. The government uses "unified budget" accounting. This means they lump the Social Security Trust Fund in with the general operating budget.

Back in the late 90s, the "Baby Boomers" were in their peak earning years. They were paying massive amounts into Social Security, but they weren't retiring yet. This meant Social Security was running a huge surplus of its own.

If you take Social Security out of the equation—what experts call the "on-budget" balance—the surplus looks a lot smaller:

- 1998: The unified surplus was $69 billion. But if you ignore Social Security, the government actually ran a $30 billion deficit.

- 1999: The unified surplus was $124 billion. The "on-budget" surplus? Just $1.9 billion.

- 2000: This was the peak. Even without Social Security, the government had $86 billion left over.

So, for at least two years, the U.S. was legitimately in the black, no matter how you sliced the data.

The Newt Gingrich Factor

While Democrats love to give Clinton all the credit, Republicans point to the "Contract with America" and the 1994 midterm elections. After the GOP took over Congress, they forced Clinton to the negotiating table.

✨ Don't miss: Charlie Kirk in Hell: Why a Viral Meme Refuses to Die

This led to the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. It was a rare moment of bipartisan cooperation (after a couple of government shutdowns, of course). They agreed to limit discretionary spending and overhaul welfare. Clinton sort of pivoted to the center, famously declaring "the era of big government is over."

The truth is that Clinton provided the tax increases that fueled the revenue, while the Republican Congress provided the pressure to keep spending from ballooning alongside that revenue. It was a "forced marriage" that actually worked.

Why We Haven't Seen a Surplus Since

It didn't last. By 2002, the surplus was gone, replaced by a $158 billion deficit. A few things happened at once:

- The Dot-Com Bubble Burst: The stock market crashed, and that easy tax revenue evaporated.

- 9/11 and the War on Terror: Defense spending shot back up.

- The Bush Tax Cuts: New legislation significantly reduced the revenue coming in.

- Recession: The 2001 recession slowed down growth.

Looking back, the Clinton years were a unique moment in history where productivity, peace, and politics aligned perfectly.

Actionable Insights for Today

If you’re trying to understand how this applies to the current mess, here are the takeaways:

- Growth is the Great Eraser: You can't just cut your way to a balanced budget when the debt is this high; you need the kind of 4% GDP growth seen in the 90s to make the math work.

- Divided Government Can Work: Some of the most significant deficit reduction happened when a Democratic President and a Republican Congress were forced to compromise.

- Watch the Interest: In the 90s, the government was actually paying down the "debt held by the public." Today, interest payments on our debt are starting to cost more than the entire defense budget.

- The Social Security Trap: Don't be fooled by "unified" numbers. Always look for the "on-budget" figure to see if the government is actually living within its means or just borrowing from the retirement fund.

If you want to track where the budget is headed now, you can keep an eye on the CBO's Monthly Budget Review, which breaks down exactly how much the government is overspending in real-time.