You’ve probably seen the images. Massive walls crawling with workers, gears, and skeletons. It’s hard to miss. Diego Rivera didn't just paint; he staged visual revolutions. Honestly, calling it "art" feels a bit small. It was more like a loud, colorful argument with history itself.

He was a big man with even bigger ideas. Standing over six feet tall and weighing 300 pounds, Rivera was a force of nature. He believed that art belonged to the people, not just rich folks in quiet galleries. This belief is what made Diego Rivera famous artwork so controversial—and so enduring.

The Mural That Got Hammered to Pieces

Most people know about the "Rockefeller Incident." It’s basically the ultimate "artist vs. boss" story. In 1933, Nelson Rockefeller—yeah, that Rockefeller—hired Rivera to paint a mural for the RCA Building in New York. The theme was supposed to be about human progress.

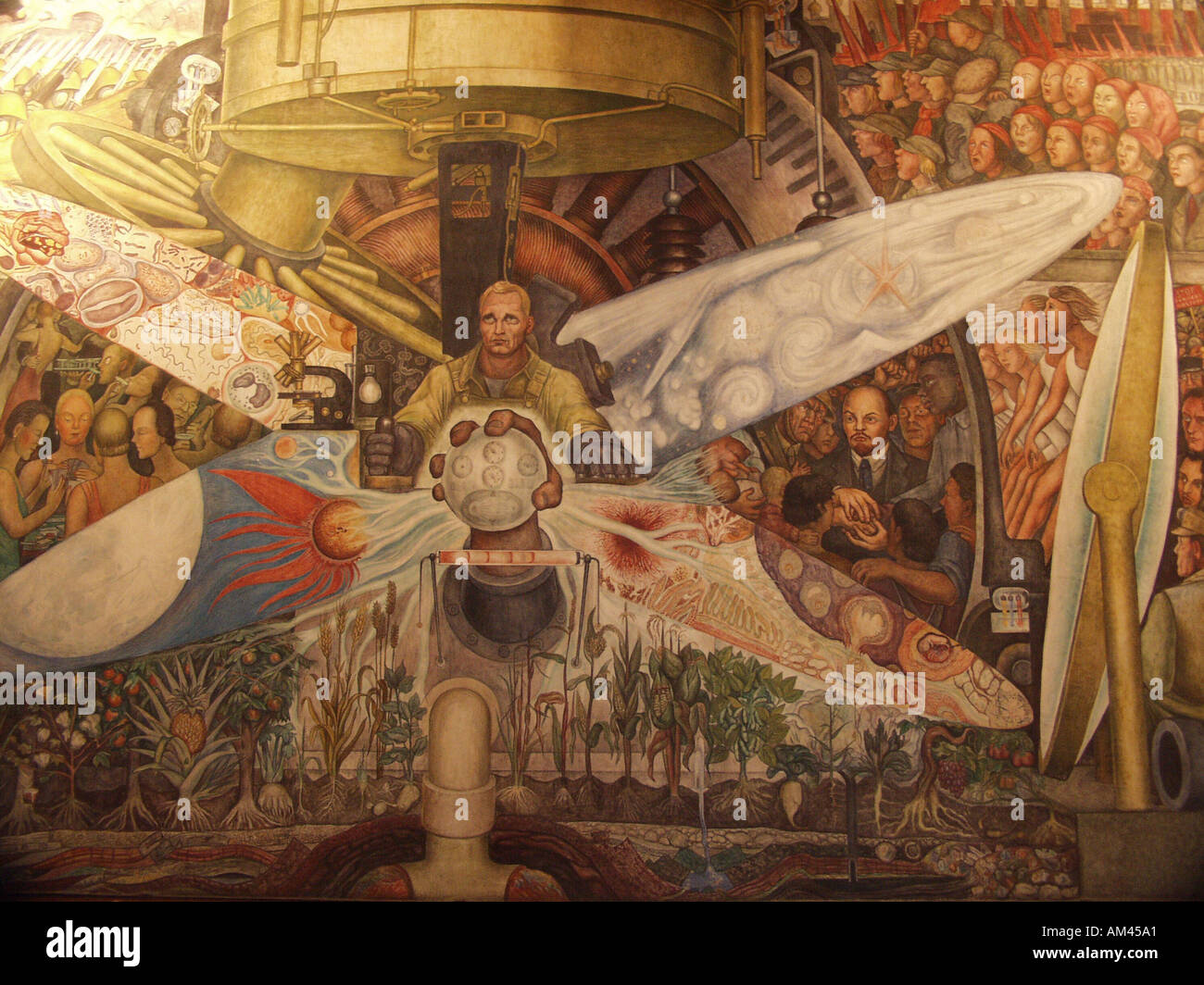

Rivera titled it Man at the Crossroads. But he couldn't help himself. He added a portrait of Vladimir Lenin holding hands with workers. Rockefeller wasn't thrilled. He asked Rivera to change it. Rivera said no.

The result?

Guards marched Rivera off the property. The mural was covered in tarp and eventually smashed to bits with hammers in February 1934. Imagine that. One of the most significant pieces of 20th-century art, turned into rubble because of a single face. Rivera didn't back down, though. He went home to Mexico City and repainted it at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, calling the new version Man, Controller of the Universe. It's still there today, Lenin and all.

🔗 Read more: Why Highway to Heaven Still Hits Different Decades Later

The Detroit Industry Murals: A Love Letter to Steel

If you ever find yourself in Michigan, you have to go to the Detroit Institute of Arts. Rivera spent 1932 and 1933 living in the city, obsessed with the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant. He saw the machines as modern-day Aztec gods.

The Detroit Industry Murals consist of 27 panels. They are a dizzying maze of assembly lines and muscle. Rivera saw the beauty in the grease. He didn't just paint the cars; he painted the chemical processes, the vaccines being made, and even poisonous gas bombs. He wanted to show that technology could either save us or kill us.

- The North Wall: Focuses on the production of the 1932 Ford V-8 engine.

- The South Wall: Shows the exterior of the car being pressed by massive machines.

- The Hidden Symbolism: Look closely at the machines. Rivera shaped them to look like Coatlicue, the Aztec mother of gods.

Local critics at the time called it "vulgar" and "un-American." There were even calls to have it whitewashed. Thankfully, Edsel Ford stepped up and basically told everyone to pipe down. He knew it was a masterpiece.

Walking Through a Dream in Alameda Park

In 1947, Rivera painted Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park. It’s a 50-foot-long fresco that functions like a time machine. You’ve got 400 years of Mexican history all hanging out in one park.

In the center, a ten-year-old Diego Rivera holds hands with a skeleton. That skeleton is La Catrina, a parody of upper-class vanity. Standing right behind them is Frida Kahlo, Rivera’s wife and fellow icon, resting her hand on his shoulder. It’s surreal. It’s personal.

The mural reads from left to right. On the left, you see the dark days of the Spanish Conquest. In the middle, the bourgeois "dream" of the Porfirio Díaz era. On the right, the fire of the Mexican Revolution. It’s not just a painting; it’s a narrative of survival.

What Most People Get Wrong About His Style

People often lump Rivera in with "Socialist Realism." That’s a mistake. He was way more complicated than that.

Rivera spent years in Europe during the height of the Cubist movement. He was buddies with Picasso. If you look at his early work, like Zapatista Landscape — The Guerrilla (1915), it’s full of fractured planes and abstract shapes. Even when he moved into his famous mural style, he kept those lessons. He used simplified, heavy forms and vibrant colors that felt modern but looked ancient.

He was trying to create a "Mexican" style that didn't just copy Europe. He wanted to honor the indigenous cultures that had been erased for centuries. That’s why his figures have those thick, rounded limbs—they look like they’re made of the earth itself.

👉 See also: Why Half a Life Star Trek Still Makes Us Uncomfortable Decades Later

Why Should You Care Today?

Art can feel like a homework assignment sometimes. But Rivera’s work is different because it’s so raw. It’s about the tension between the guy holding the wrench and the guy holding the checkbook. That hasn't changed.

If you want to truly experience Diego Rivera famous artwork, you can't just look at a screen. These works were designed for specific rooms. They interact with the light and the architecture.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Virtual Tour: If you can't get to Mexico City, the Diego Rivera Mural Museum offers high-res digital views of the Alameda Park mural. Spend ten minutes just zooming in on the faces.

- Visit Detroit: If you are in the Midwest, the Rivera Court at the DIA is one of the few places in the world where you can stand in the middle of a complete "Rivera environment." It’s a spiritual experience even if you aren't into cars.

- Check the National Palace: The History of Mexico murals in the National Palace (Mexico City) are free to view but require a bit of planning with security. It’s worth the line.

Rivera’s legacy isn't just about the paint. It’s about the fact that he forced people to look at the workers, the peasants, and the rebels. He made sure they couldn't be ignored. He turned the walls of power into a mirror for the powerless.