You’ve probably seen a flash of orange and black in your backyard and immediately thought, "Oh, a Monarch." Most people do. But there’s a solid chance you were actually looking at a Viceroy, a completely different species that just happens to be a master of disguise. It's wild how much we overlook when it comes to the sheer variety of these insects. There are roughly 17,500 species of butterflies worldwide. Think about that number for a second. That is a massive amount of biological diversity flying right over our heads while we're busy staring at our phones.

Different types of butterflies aren't just "pretty bugs." They are specialized survivors. Some migrate across continents, while others spend their entire lives within a few hundred yards of where they hatched. Some have wings that look like dead leaves to hide from birds, and others use bright, neon "warning" colors to scream, "Don't eat me, I taste like literal poison." If you want to actually know what you’re looking at next time you’re outside, you have to look past the colors and start noticing the wing shapes, the flight patterns, and the host plants they hang around.

The Big Families You Actually Need to Know

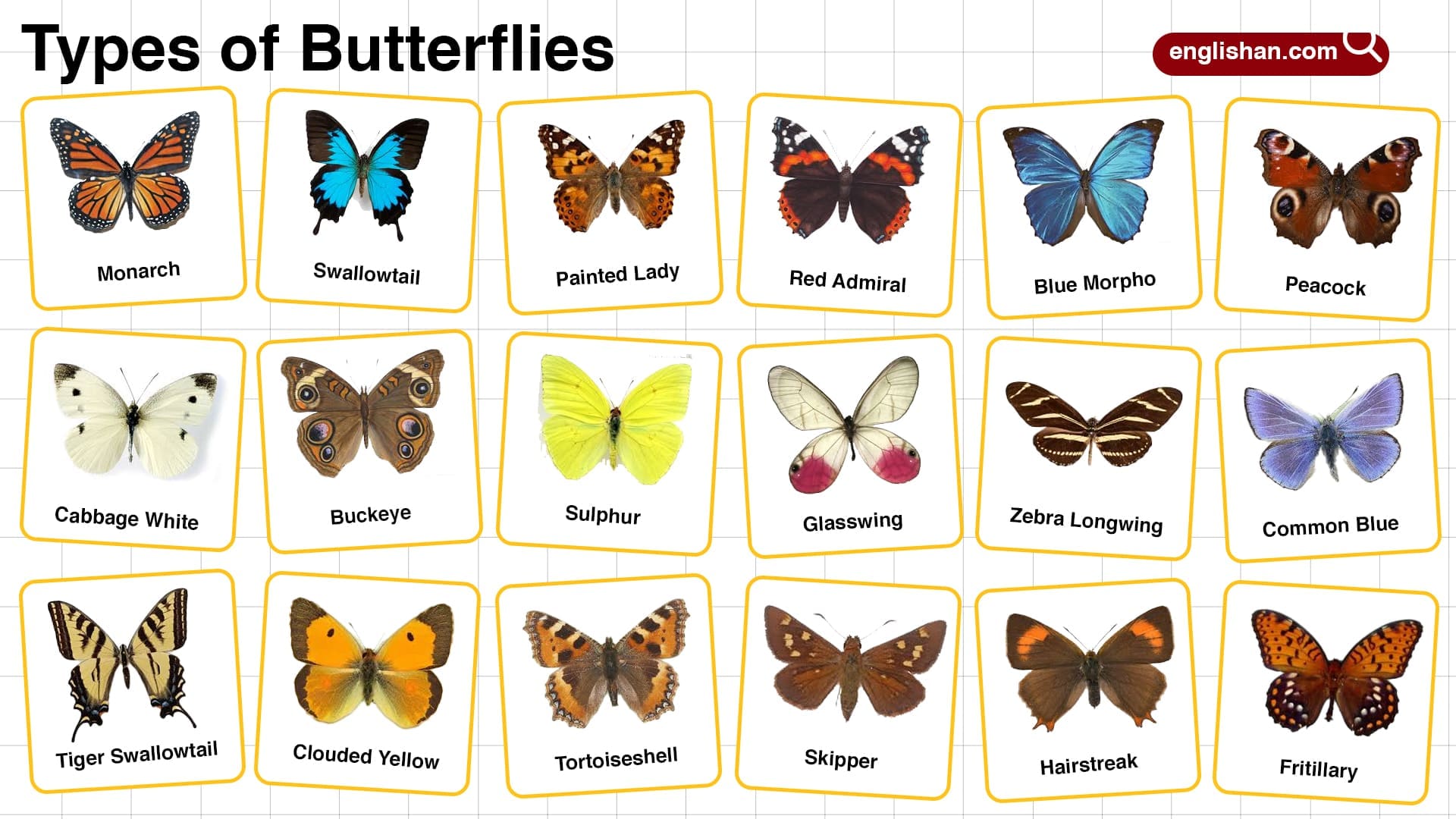

Scientists don't just group butterflies by color because that would be a mess. Instead, they use families. Most of what you see in North America and Europe falls into a few specific buckets.

Take the Papilionidae family, commonly known as Swallowtails. These are the heavy hitters. They’re usually big—sometimes huge—and most of them have those distinct "tails" on their hindwings that look like the forks on a swallow's tail. The Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) is a classic example. You’ve seen them; they’re the big yellow ones with black stripes. But here’s a weird fact: in some areas, the females can be almost entirely black. This is called dimorphism. They do it to mimic the Pipevine Swallowtail, which is toxic. Evolution is basically just a long game of "copy the guy who doesn't get eaten."

Then you have the Nymphalidae, or Brush-footed butterflies. This is the largest family. If you look closely at a Painted Lady or a Monarch, it looks like they only have four legs. They actually have six, but the front two are tiny and hairy, tucked up near their heads. They basically use them as sensory organs to "taste" the plants they land on. Imagine walking around and tasting the ground with your arms. That’s their life.

💡 You might also like: In the Light Book: Why Aletha Solter’s Approach to Childhood Trauma Still Matters

Why We Keep Mixing Up the Monarch and the Viceroy

The Monarch (Danaus plexippus) is the poster child for different types of butterflies. Everyone knows them. They’re famous for that incredible multi-generational migration to Mexico. But the Viceroy (Limenitis archippus) is the one that trips people up. For years, we thought the Viceroy was a "Batesian mimic," meaning it was a harmless butterfly pretending to be a toxic Monarch to fool predators.

Recent studies have flipped that script. It turns out the Viceroy is also pretty bitter and unpalatable to birds. This is actually Müllerian mimicry, where two or more species that are both unsavory evolve to look like each other. It’s a "strength in numbers" strategy. If a bird eats a Viceroy and hates it, it’ll leave the Monarchs alone too. It’s an efficient way to train predators. To tell them apart, look at the hindwing. A Viceroy has a horizontal black line crossing through the vertical veins. Monarchs don't have that line. It’s a small detail, but it’s the "tell."

The Tiny Blues and Hairstreaks You’re Stepping Over

While everyone is chasing the big Swallowtails, there is an entire world of "Micro-butterflies" in the Lycaenidae family. These are your Blues, Coppers, and Hairstreaks. They’re small. Sometimes the size of a fingernail.

The Karner Blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) is a famous one because it’s incredibly rare and endangered. It depends entirely on the wild blue lupine plant. No lupine, no Karner Blue. This is the downside of being a specialist. If your specific "grocery store" goes out of business, you’re done.

Many Hairstreaks have tiny "fake heads" on the back of their wings. They have little tails that look like antennae and spots that look like eyes. When they sit on a flower, they wiggle their back wings. A bird strikes at the "head," gets a mouthful of wing-dust, and the butterfly flies away with a slightly chipped wing but its actual head intact. It’s brilliant.

Misconceptions About What Butterflies Actually Do

People think butterflies just spend all day sipping nectar from flowers. Sorta, but not really. While they do need sugar for energy, many different types of butterflies need minerals that they can't get from roses or daisies.

Have you ever seen a group of butterflies huddling around a mud puddle? It’s called "puddling." They’re mostly males, and they’re sucking up salts and minerals from the wet dirt. They need these nutrients to produce pheromones and to pass on to females during mating to help with egg production. Sometimes they’ll even land on you to drink your sweat. It’s not because they like you; they just want your salt. Some species in the tropics will even go for rotting fruit, animal dung, or—and this is a bit grim—decaying carcasses. Nature isn't always pretty.

How Temperature and Climate Are Changing the Map

The distribution of different types of butterflies is shifting. Fast. Because they are cold-blooded, butterflies are like "living thermometers." They are extremely sensitive to temperature changes.

The Giant Swallowtail used to be a strictly southern bird. Now? It’s being spotted regularly in southern Canada. As the planet warms, species are moving north to find the specific temperature "sweet spot" they need to survive. But here’s the problem: the butterflies move faster than the plants. If a butterfly moves north but its host plant (the only thing its caterpillars can eat) hasn't grown there yet, that population hits a dead end.

The Mystery of the "Leaf" Butterflies

If you ever travel to tropical Asia, keep an eye out for the Dead Leaf Butterfly (Kallima inachus). This is peak evolution. When its wings are open, it’s a brilliant flash of blue and orange. But when it closes them, it looks exactly like a brown, crunchy leaf. It even has markings that look like mold spots and a "midrib" line that mimics a leaf vein.

It can sit in plain sight on a branch and be completely invisible to a hungry lizard. This kind of camouflage is a reminder that different types of butterflies have spent millions of years in an arms race against predators.

Actionable Insights for Your Own Backyard

If you want to actually see these different types of butterflies instead of just reading about them, you have to change how you garden. Stop buying "pretty" flowers from big-box stores that have been treated with systemic pesticides. Those chemicals get into the nectar and can kill the very insects you're trying to attract.

- Plant Host Plants: Most people plant nectar plants (food for adults), but they forget host plants (food for caterpillars). Monarchs need Milkweed. Black Swallowtails need Dill, Parsley, or Fennel.

- Leave the Leaves: Many species, like the Mourning Cloak, spend the winter as adults or pupae hidden in leaf litter. When you "clean up" your garden in the fall, you're often throwing away next year's butterflies.

- Create a Puddling Station: You don't need a fancy fountain. Just a shallow dish with some sand and water. Keep it damp. Maybe add a pinch of sea salt. Watch the males flock to it.

- Avoid Neonicotinoids: Always ask your nursery if their plants have been treated with "neonics." These are long-lasting insecticides that are devastating to pollinator populations.

Identifying butterflies is a skill. It takes time. You’ll get it wrong at first. You’ll call a Cabbage White a moth (moths usually rest with their wings flat or tented, butterflies usually rest with them closed upright). But once you start noticing the subtle differences—the way a Red-spotted Purple glides versus the frantic flapping of a Skipper—the world gets a lot more interesting.

Nature is nuanced. It's not just a list of species; it's a web of connections between the soil, the plants, and these fragile, incredibly resilient insects. Keep your eyes open. The more you look, the more you'll see.